Written byNola Taylor Redd

The brutal deserts of Australia may not be the first place you think of when you want to study life. Yet this harsh environment has helped propel the Australian Center for Astrobiology (ACA) to the forefront of its field by maintaining records of the youthful environment of our world and providing a stand-in for Martian exploration.

“Australia is host to what is arguably the best preserved, most complete record of early Earth, including some of the oldest evidence for life on our planet,” says geologist and astrobiologist Martin Van Kranendonk, head of the ACA.

Martin Van Kranendonk, who is Director of the Australian Center for Astrobiology, doing field work in the Pilbara.Image credit: Eben Rose.

The birth of a center

Geologist Malcom Walter founded the ACA at Sydney’s Macquarie University in 2002. Today, it is the only center of astrobiological research in Australia. Along with the Centro de Astrobiolgia in Spain, the ACA was one of only two formal international associate members of NASA’s Astrobiology Institute (NAI), according to Carol Oliver, the Deputy Director of the ACA who helped Walter establish the Center 15 years ago. The association with NASA gives the ACA a seat on the Institute’s Executive Council today. That seat has helped several of the center’s members play important roles in NASA missions, as well as securing participation at NAI-funded centers, and other projects supported by the wider NASA Astrobiology Program, Van Kranendonk says.

“The driver was, of course, the unique role Australia has in searching for life on Mars,” Oliver says. “We have some of the most convincing evidence of life on Earth from almost 3.5 billion years ago in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. It makes a very good analog for looking for life on Mars.”

During the center’s early years, this evidence for early life was still controversial, Oliver says. Walter, who described his journey from geologist to astrobiologist in an article for the journal Astrobiology, was involved in the early studies from a geologic perspective, but he didn’t become interested in life on Mars until the late 1980s. After the ACA was founded, ongoing research provided confidence that the stromatolite layers of Pilbara are evidence for Earth’s early life, produced by single-celled cyanobacteria, although some still debate the subject.

“The ACA specializes in all aspects of early Earth, but especially in ancient life,” Van Kranendonk says. “Researchers come from all over the world to work with us and visit our sites.”

According to Oliver, the center’s three key areas are the earliest life on Earth, living stromatolites, and exoplanets. In addition to scientific research, the ACA also has another core branch.

“One very novel goal at the outset of the ACA was to integrate the science research with the science communication and education outreach,” Oliver said. That includes courses for students, both locally and online, and the construction of a Mars Yard for both research and the general public. The Yard has been visited by notables such as Microsoft’s Bill Gates, the US ambassador to Australia and the former NASA Chief Administrator Charles Bolden, Van Kranendonk said.

The Australian Center for Astrobiology maintains the largest Mars Yard in the world at Sydney's Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences.Image credit: ACA.

“I have an absolute belief in the importance of communicating with the public,” says Walter. “By conveying the excitement of discovery, we attract young people to science and encourage the public to fund our work.”

The ACA doesn’t just provide an academic look at the desert. Visiting researchers are able to explore early habitable environments for an up-close glimpse of early life on Earth, inspecting the mollusks and microbial life off the coast of Western Australia as well as the banded iron formations and ancient gorges of the Pilbara region, where fossils are plentiful.

“Our calling card is a bi-annual Grand Tour field trip that runs from the living stromatolites at Shark Bay – we snorkel with them – and then back through time, across the Outback of Australia, to the oldest life on Earth,” Van Kranendonk says. The continental tour coincides with the Australasian Astrobiology Conference hosted by the ACA, where researchers can come to present and discuss their work.

The 140-square-meter (1,500 square feet) Mars Yard, found in Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, combines both public outreach and research opportunities. The center maintains three experimental Mars rovers at the yard, which is an Earth-like replica of the environment on Mars, where rocks and dunes can provide a landscape much like the ones crisscrossed by NASA’s rovers. Van Kranendonk says theirs is the largest Mars Yard in the world. Combined with a super-fast internet connection and video conferencing, this allows students in Australia and around the world to run a Mars mission from their classroom.

In 2008, the ACA moved to the University of New South Wales. “This turned out to be a really good move,” says Oliver. The support from their new institution allowed them to build on their previous successes.

Over the past 15 years, the ACA has continued to grow and expand. “I would say we have exceeded our [original] goals both in science and in science communication and education,” says Oliver.

Stromatolites like those found in Shark Bay, Western Australia, provide the necessary comparisons for interpreting analogues from early Earth history.Image credit: S M Awramik.

Exploring the Outback

The ACA’s unique location provides several advantages when it comes to studying astrobiology on the continent. Perhaps the biggest benefit of studying astrobiology in Australia is the aforementioned strong evidence for life on Earth 3.5 billion years ago.

The unique rock record matters not only for understanding how life on Earth evolved, but also for how it could gain a foothold on other planets.

“That is important in the search for life on Mars, because that is when life on Mars may also have gotten for started,” Oliver says. When it comes to hunting for microbial alien life, understanding how and when that life gained a foothold on Earth is key. Australia’s deserts provide an idea of what early microbial life on the red planet could have looked like.

“Our research is used to inform NASA where to search for life on Mars,” says Van Kranendonk. He has attended and presented at the last two Landing Site Workshops for NASA’s upcoming Mars 2020 mission.

Several of the ACA’s former students highlight its connection to Mars. In 2006, then-doctoral student Abigail Allwood showed that the Strelley Pool Chert stromatolites in the rock formations of Pilbara region were made by biology rather than geology.

“Abby pointed out that the evidence for a microbial reef [that is] 3.43 billion years old was so powerful that it made the life explanation the ordinary, plausible interpretation, whereas the opposite – that this was simple geology – was actually the extraordinary claim,” says Oliver.

Allwood went on to a postdoctoral position at NASA’s Jet Propulsion laboratory. In 2017, she was named as one of the seven principle investigators of an experiment on board Mars 2020, making her the first woman and the first Australian to lead an experiment on a Mars rover mission.

Adrian Brown, who received his doctorate from the ACA, has recently been appointed as Deputy Program Scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration, while a third, David Flannery, has joined Allwood’s team to study the red planet.

According to ACA microbiologist Belinda Ferrari, “The benefit of the Center and studying astrobiology is the bridging of disciplines, from microbiologists studying analogs to life on Mars to geoscientists investigating the oldest forms of life.”

A member of the Center, Ferrari has had a close connection to the ACA since she joined the UNSW staff in 2009. After working with microbes through her career, her recent discovery of soil microbes scavenging trace gases to survive in the frigid Antarctic environment has provided a link to astrobiology.

“This minimalistic mode of survival opens up the possibility of atmospheric gases supporting life on other planets, so this research has strengthened my involvement in the Center,” Ferrari says, as the new research increased her interest in astrobiology.

For Clark Johnson, a geochemist at the University of Wisconsin, the best part of working with the ACA has been the “wonderful colleagues.”

“Both the current head of the ACA, Martin Van Kranendonk, and the previous, Malcolm Walter, have a well-deserved reputation for welcoming international collaborations and are very generous with their time, including spending extensive field time with collaborators,” says Johnson. “That is essential. Not only does one need to spend time with the rocks to understand them, it is the process of spending time in the field, away from the office, that helps one to develop ideas.”

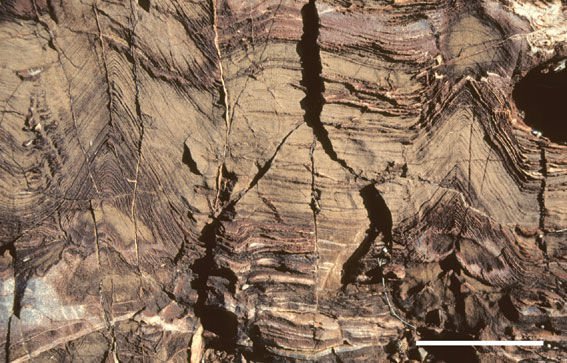

Structures in the Strelley Pool Chert rock formations in Western Australia suggest that microorganisms thrived in shallow marine environment 3.4 billion years ago.Image credit: S M Awramik.

The isolation of the continent has created some difficulties for those wanting to work with the ACA. “The challenges of studying astrobiology in Australia are mainly confined to international students – it is expensive to live and study in Sydney, and research scholarships are extremely hard to get,” Oliver says. She points out that some countries have scholarships in place that allow students to spend some or all of their research training in the country.

“It is a bit of a way to travel, so you don’t just pop over for a chat,” says Johnson.

Technology can go a long way to help bridge the gap. Johnson says that videoconferencing helps, although the substantial difference in time zones remains a challenge. Online courses are also a benefit. About 15 percent of the students in their third-level, fully-online astrobiology course are overseas students that are part of the Institute’s Study Abroad program, says Oliver.

Another stumbling block is funding, which Van Kranendonk says has been a challenge for the field of astrobiology in general.

“Because astrobiology is a combination of all the sciences, the best way is to apply for funding within each area of science,” Oliver says. She describes how the ACA has obtained three very large grants for astrobiology in education and outreach over the last six years. Two of those grants, from the Australian Space Research Program and the Australian government’s Broadband-Enabled Education and Skills Services Program, helped to set up the Mars Yard.

Funding may become less of a challenge in the future, thanks to the recent announcement that Australia will have soon have its own space agency. An Australian space agency makes sense, says Oliver, “because Australia needs to be part of the global conversation in civil space as well as defense space.”

She sees the upcoming commitment as a plus for astrobiology as well, making it a boon for the ACA.

“The Australian Space Agency will also provide the kind of vision and inspiration that drives all space agencies,” Oliver says. “This is surprisingly important both in the business of space and in encouraging young people to take Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) courses.”

International Partner Series:

The Astrobiology Society of Britian

The UK Centre for Astrobiology

German Aerospace Center: Institute of Planetary Research

Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología

Sociedad Mexicana de Astrobiología (SOMA)