Written bySarah Wild

With its multidisciplinary scope, astrobiology is “a return to the 19th century, in that it’s a field that has little regard for the 20th century disciplinary boundaries,” says Charles Cockell, Director of the United Kingdom Centre for Astrobiology (UKCA). Given the range of diverse disciplines and the number of academics in the United Kingdom who are interested in astrobiology, it has not been possible to fit them all under one physical roof. So the UKCA has gone virtual.

The centre, which was established in 2011 and began operations in 2013, includes philosophers and social scientists, as well as engineers, biologists and physicists. While there is a lot of exciting physical science, astrobiology also opens the door to the sort of philosophical questions often absent from the natural sciences, Cockell says. “What would be the consequence of finding ET? What are the long-term ob-jectives of humanity? Astrobiology provides a backdrop to those discussions.”

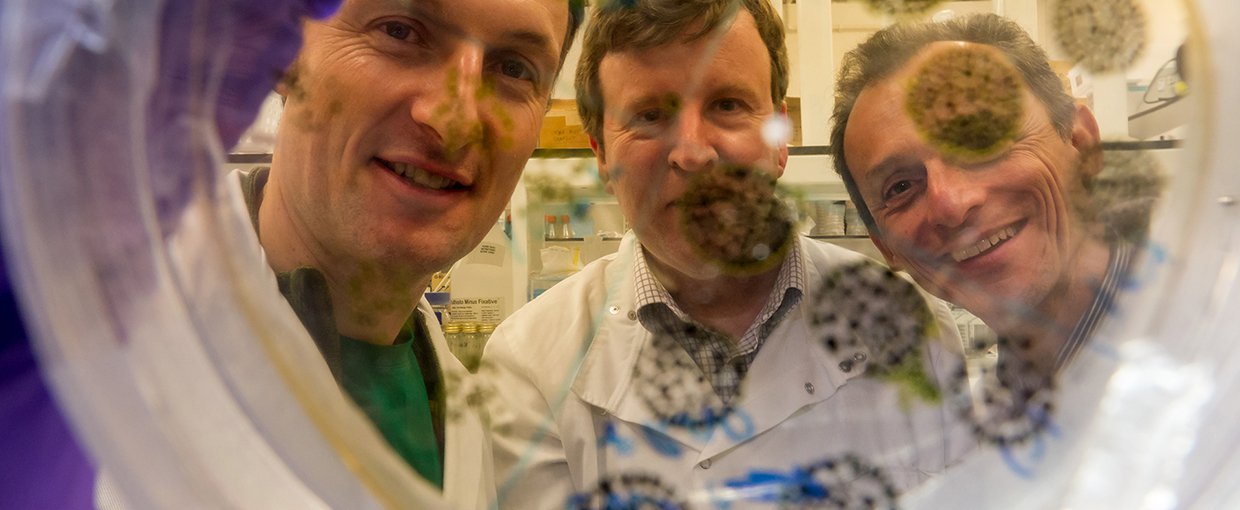

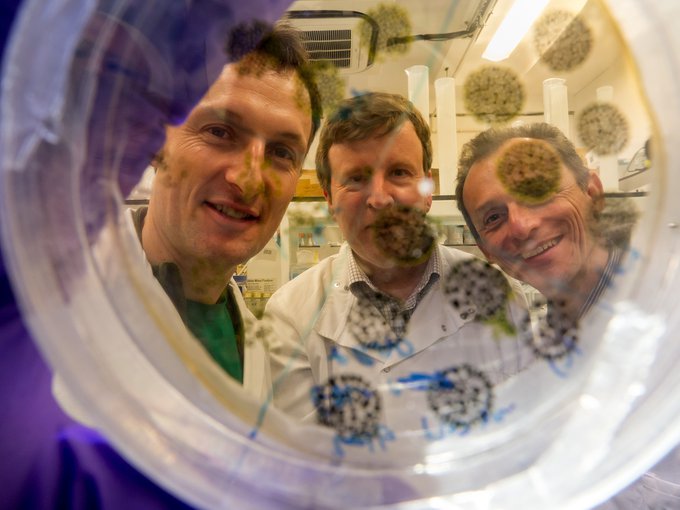

The UK Centre for Astrobiology runs numerous courses, including geology courses for astronauts at the University of Edinburgh, UK. Pictured here are ESA astronauts Pedro Duque (right) and Matthias Maurer (left) with Charles Cockell (centre).Image credit: ESA/S. Sechi.

To provide an example, he refers to a multi-institution collaboration of social scien-tists, coordinated by Cockell at the UKCA, who are investigating the social implica-tions of space exploration. “Astrobiology brings people together who would normal-ly be siloed into departments,” he says. The centre is “a rallying point for people who want to think about big questions”.

Teaming Up

Although its physical footprint is at the University of Edinburgh, which is where Cockell is based, the UKCA includes partnerships between researchers all over the country, as well as internationally.

Javier Martin-Torres met Cockell in 2013 at a meeting held by the UKCA and the British Interplanetary Society in London about Extraterrestrial Liberty and The Meaning of Liberty Beyond Earth. Martin-Torres currently leads a planetary science and at-mospheric research group at the Luleå University of Technology in Sweden. “I am a physicist and I wanted to know Cockell’s opinion on the implications of [water on Mars] from a microbiology point of view,” remembers Martin-Torres. The two have been collaborating ever since and in 2017 Martin-Torres became a visiting scholar at the UKCA.

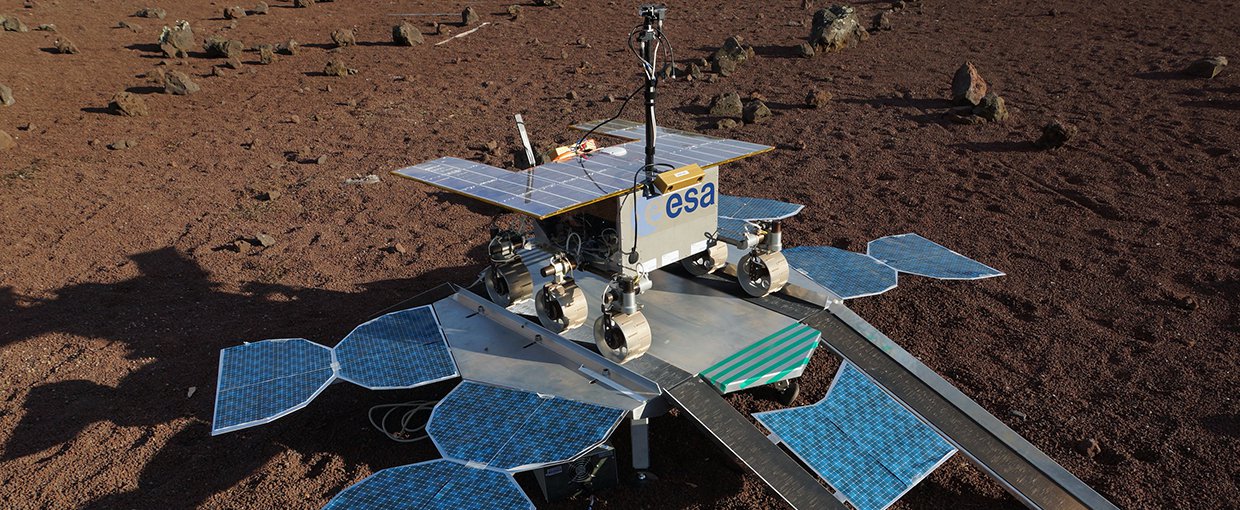

Martin-Torres is the principal investigator of the HABIT (HAbitability, Brines, Irradia-tion and Temperature) instrument, which will be part of the Surface Science Plat-form component on the joint Russian/European Space Agency ExoMars 2020 mis-sion, which will also feature a rover that will traverse the Martian surface searching for signs of life. Cockell, who is a co-investigator, will “study the habitability in brines under Martian environmental conditions, and analog site testing,” Martin-Torres says.

“We will use data from HABIT, UKCA laboratories, field campaigns, ExoMars, Curi-osity and other NASA instruments to answer fundamental questions [such as], when and where did liquid water exist on Mars? What are the environmental condi-tions, namely temperature and radiation levels, compatible with organic preserva-tion, and microbial reproduction and metabolism limits? And what are the implica-tions of habitability to present and future Mars exploration?”

Scientists led by Charles Cockell of the UK Centre for Astrobiology ventured deep underground inside Boulby Mine in north-east England, to conduct experiments as part of the European Space Agency’s Pangaea geology course for astronauts and scientists.Image credit: UK Centre for Astrobiology.

The answers to these questions can only be found through collaboration, he says. “We are living in a privileged period. The Internet, new technologies and the cost of travel make collaborations a very easy effort. It is possible to organize teleconfer-ences with people from all over the world, and the use of e-mail is fundamental.”

Going Underground

However, some collaborations require people on the ground – more than one-kilometer underground, in fact. In one of the deepest mines in Europe, namely Boulby Mine, which is a potash mine in Cleveland, north-eastern England, astrobi-ology instruments share space with dark matter detectors. The astrobiology instru-ments form part of the Boulby International Subsurface Astrobiology Lab (BISAL), a microbiology laboratory that is an analog for the conditions on other planets. It was the world’s first permanent deep subsurface astrobiology experiment.

“Many of the challenges faced by planetary scientists, such as building small minia-turized instruments that are lightweight, require low energy and operate in ex-tremes, are also challenges faced by those in the deep subsurface mining sector,” say authors of a paper from the UKCA detailing the establishment of BISAL.

Deep subsurface miners want instruments that can “detect and quantify ore quality, map and study subsurface tunnels and structures and check underground envi-ronments for safety,” and Boulby Mine provides an excellent opportunity to carry out planetary science work deep underground. A 2008 paper investigating under-ground habitats in the Río Tinto basin in Spain suggests that astrobiologists should be searching for Martian life below the red planet’s surface.

The lab is also part of an analog program, conducted in conjunction with NASA.

“It allows for international collaboration, and it’s something we bring to the [collabo-ration] table on a practical science level,” Cockell says.

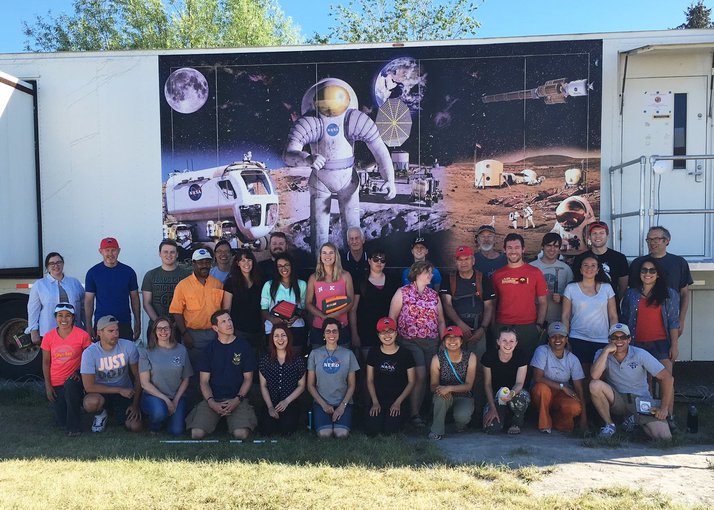

Another on-the-ground program is BASALT, run by the NASA Ames Research Cen-tre. The UKCA, which became affiliated to the NASA Astrobiology Institute in 2012, is also part of the program and Cockell leads its biology section. BASALT, short for Biologic Analog Science Associated with Lava Terrains, aims to mimic Martian conditions in volcanic landscapes in Idaho and Hawaii in the United States, to de-termine the habitability of these environments and how humans and robots could explore and inhabit Mars.

Darlene Lim, principal investigator on the BASALT program, says that UKCA col-laborators bring more than just their expertise. “The UCKA contributors have been some of the most stand-out collaborators amongst a large group of high achievers,” she says. “They have brought thoughtful and researched input to not only our sci-entific discussions, but also those associated with our operations and technology development activities.”

They are also “such a collegial and enjoyable bunch to be with in the field,” she adds. “Fieldwork is intense any way you slice it, and keeping humor and flexibility in the mix is so important in terms of maintaining morale.”

A schematic of Boulby Mine in North Yorkshire, which conducts both astrophysical and astrobiology experiments, the latter using the mine as an analog for subterranean Mars.Image credit: STFC.

Behind bars

While many societies and institutions have outreach programs, Cockell has started something quite different: a prison astrobiology outreach program. In December 2017, the UKCA completed its first ‘Life Beyond’ course in two Scottish prisons. A collaboration between the UKCA and the Scottish Prison Service, it involves in-mates designing plans for human stations on Mars.

The centre will also be conducting a life-support research program in one of these prisons, with prisoners undertaking real research into how to grow food on Mars.

“It’ll be the world’s first life-support system in a prison,” Cockell enthuses. “They’re doing real experiments [such as the amount of fertilizer required, nutrient contents], which I’m excited about as well. The only problem is that they can’t have their full names on [the papers that are published as part of these experiments], so they can have anonymity when they come out of prison,” he says.

The papers authored as part of these initiatives will have the authors’ first names, though, he says, so that “they will get credit for the work”.

This year, the Life Beyond course will be offered at two other Scottish prisons.

“There’s a lot of curriculum work out there,” says Cockell, “but little work done in prisons. Astrobiology is a very inspiring science – it covers such big questions, and so is a vehicle for education, whether in schools or prisons. It’s a powerful science.”

Researchers from NASA Ames’ BASALT (Biologic Analog Science Associated with Lava Terrains) project, among which are scientists from the UK Centre for Astrobiology, gather for a photograph during a field trip to Idaho in June 2016.Image credit: John Hamilton.

International Partner Series:

Australian Center for Astrobiology

The Astrobiology Society of Britian

German Aerospace Center: Institute of Planetary Research

Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología

Sociedad Mexicana de Astrobiología (SOMA)

Other resources:

UKCA

Boulby International Subsurface Astrobiology Laboratory

Boulby Underground Laboratory

BASALT

Life Beyond

Astrobiology Society of Britain (ASB)

Cockel et al. (2018) “The UK Centre for Astrobiology: A Virtual Astrobiology Centre. Accomplishments and Lessons Learned, 2011–2016,” Astrobiology, 128(2). DOI 10.1089/ast.2017.1713