Finding new worlds can be an individual effort, a team effort, an institutional effort. The same can be said for characterizing exoplanets and understanding how they are affected by their suns and other planets in their solar systems. When it comes to the search for possible life on exoplanets, the questions and challenges are too great for anything but a community. NASA’s NExSS initiative has been an effort to help organize, cross-fertilize and promote that community. This artist’s concept Kepler-47, the first two-star systems with multiple planets orbiting the two suns, suggests just how difficult the road ahead will be.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle.

The Nexus for Exoplanet System Science, or “NExSS,” began four years ago as a NASA initiative to bring together a wide range of scientists involved generally in the search for life on planets outside our solar system.

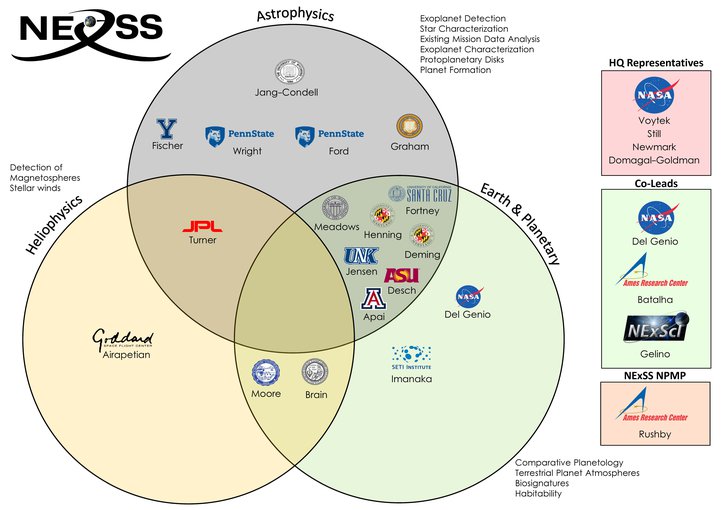

With teams from seventeen academic and NASA centers, NExSS was founded on the conviction that this search needed scientists from a range of disciplines working in collaboration to address the basic questions of the fast-growing field.

Among the key goals: to investigate just how different, or how similar, different exoplanets are from each other; to determine what components are present on particular exoplanets and especially in their atmospheres (if they have one); to learn how the stars and neighboring exoplanets interact to support (or not support) the potential of life; to better understand how the initial formation of planets affects habitability, and what role climate plays as well.

Then there’s the question that all the others feed in to: what might scientists look for in terms of signatures of life on distant planets?

Not questions that can be answered alone by the often “stove-piped” science disciplines — where a scientist knows his or her astrophysics or geology or geochemistry very well, but is uncomfortable and unschooled in how other disciplines might be essential to understanding the big questions of exoplanets.

The original NExSS team was selected from groups that had won NASA grants and might want to collaborate with other scientists with overlapping interests and goals but often from different disciplines.Image credit: NASA/NExSS.

The original idea for this kind of interdisciplinary group came out of NASA’s Astrobiology Program, and especially from NASA astrobiology director Mary Voytek and colleague Shawn Domogal-Goldman. It was something of a gamble, since scientists who joined would essentially volunteer their time and work and would be asked to collaborate with other scientists in often new ways.

But over the past four years NExSS has proven itself to be very active and useful in terms of laying out strategies for tackling the biggest questions in the field of exoplanets and whether they might harbor life. In two major reports last year, the private, congressionally-mandated National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine held up NExSS as a successful model for moving the science forward.

One of the study co-chairs, David Charbonneau of Harvard University, said after the release of the study that the “promise of NExSS is tremendous…We really want that idea to grow and have a huge impact.”

This major report from the National Academy of Sciences last year endorsed NExSS as a program that substantially aided the exoplanet community. The report recommended that the organization be expanded.Image credit: National Academy of Sciences.

So with that kind of affirmation, it was hardly surprising that the first gathering of a newly constituted NExSS at the University of California, Santa Cruz featured 34 teams, double the original 17. (The team members, both new and original, are here.)

As explained at the opening of the gathering by Voytek and others, the NExSS approach is all about creating, expanding and promoting the fast-growing fields of exoplanet habitability and astrobiology more generally.

“The original NExSS members were in service to all of you,” she told the group. “They provided the opportunity to help your community to push questions further and also to get NASA headquarters to give some necessary attention to what you are doing.”

And in many ways they succeeded. The NExSS teams may not have gotten funded additionally for their work, but the group’s rising profile created important advisory opportunities for participants.

From the first NExSS groups, for instance, scientists were selected for leadership roles in the main exoplanet science group and several for science and technology definition teams. These groups established by NASA are putting together four proposals for a grand observatory for the 2030s — a hoped-for successor to the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope.

NExSS members also were called on to organize in-depth workshops on subjects ranging from defining and interpreting biosignatures on distant planets, to the centrality of exoplanet interiors and most recently to what signs of advanced technological civilizations might be detectable. Major white papers were generally written, submitted and published in journals following these NExSS workshops.

“I think putting together NExSS is most successful thing I’ve done in my career in NASA,” said Voytek who, in her decade-plus at the agency, has worked to change attitudes about astrobiology and interdisciplinary work. “I’m proud of what you did and we did.”

Mary Voytek is the Senior Scientist of NASA’s Astrobiology Program and a founder of the NExSS program.Image credit: ELSI.

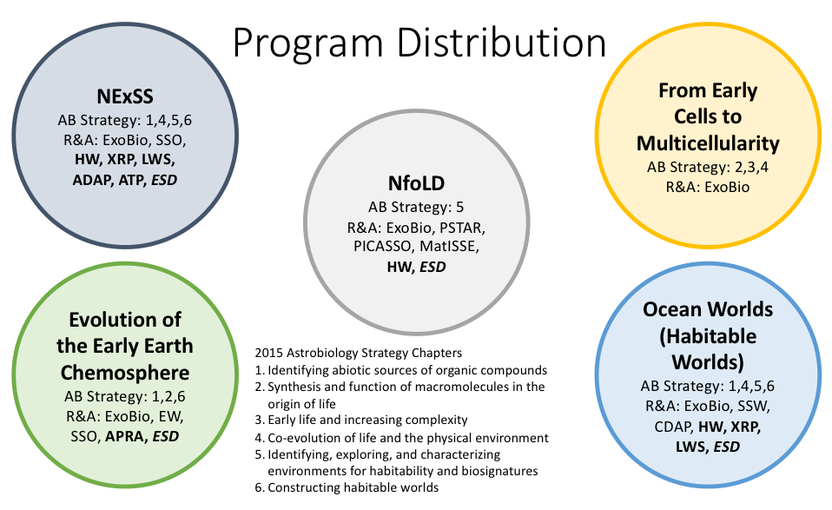

What’s more, as Voytek explained at the beginning of the meeting, the NExSS approach will spread with the creation of four new networking groups based on the model of NExSS.

They will use the same cross-disciplinary, get-to-know-your-fellow scientists approach to jump-start collaborations and cross-fertilizing in other aspects of the search for life beyond Earth, as well as the effort to understand how life on Earth (and potentially elsewhere) might have started and grown more complex.

(The four, below, focus on planetary chemistry before life, on biosignatures, on the transition from early single cell organisms to more complex ones, and on what can be learned from ocean worlds.)

This expansion, which will be part of a reorganization of NASA’s astrobiology program, will change the way that science teams will be funded and also, as Voytek put it, would “democratize” the process that NExSS began. The original program had selected many of its principal investigators from large teams and organizations, but the expanded NExSS and the four other groups to come will be more widely open to teams and individuals from smaller institutions who are earlier in their careers.

This is important, Voytek and other NExSS organizers said, because the NExSS approach allows scientists to network in ways that create science opportunities, as well as those avenues into the major prioritizing organizations in their exoplanet/astrobiology community writ large.

Initial group of NASA Astrobiology RCNs.Image credit: NASA Astrobiology.

One value of this approach can be seen in the person of planetary scientist Sarah Morrison, a postdoc at the large Pennsylvania State University exoplanet program who has been hired to teach at the much smaller Missouri State University program. She is a co-principal investigator on one of two NExSS teams at Penn State and was at last week’s Santa Cruz meeting in that capacity.

Her research focuses on protoplanetary disks and planet formation within them. In particular, she studies the many different types of interactions — collisions, migrations, atmosphere losses — that forming planets can have within their natal disks. She is also intrigued by solar systems where the planets orbit in resonance to each other.

These factors, and many others, have implications for the composition of planets and then for the possibility of life starting on them. Factors such as the eccentricity of a planet’s orbit or where it was formed within the disk can make a planet a good candidate for habitability or one where life is impossible.

Sarah Morrison is an early career planetary scientist at Penn State University, but moving to Missouri State University for a teaching position. She looks to NExSS as an invaluable network to meet collaborators and keep on the cutting edge of her field.Image credit: Many Worlds.

For Morrison, NExSS is an avenue for keeping her research vibrant.

“I’m going to a smaller institution, with not so many people doing exoplanets,” she told me. “For me to remain active in the field and work, and to have the collaborators I need to open possibilities for students working with me, this type of network can be very important – on the research side and education side.”

She said that it isn’t always easy to find scientists whose work overlaps with hers, but that at the NExSS meeting it was easy.

“I can definitely see projects down the line as a result of conversations I had with those folks,” she said. “And developing collaborations now is very important to me.”

As described by Voytek and other NExSS leaders, another major focus of the group has been to encourage NASA headquarters to embrace some of the interdisciplinary approach they practice and are convinced is necessary.

This is part of a much longer effort by Voytek and other to include the search for life beyond Earth in the missions large and small that NASA develops. There was certainly resistance at times, but the agency has, in the past decade, made that search an increasingly central NASA goal.

As described by NExSS leader (or “Jedi”) Dawn Gelino, deputy director of the agency’s Exoplanet Science Institute, NASA headquarters has responded in other ways as well, and in recent months made two of its major research grant programs interdivisional.

That means scientists from quite different but nonetheless related disciplines can — for the first time — together propose projects for funding by those NASA programs. Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate, has been forceful in his support for this kind of approach.

“As a result of NExSS, we are definitely making a difference at headquarters in terms of the structure of teams responding to calls for proposals,” Gelino said.

A NExSS interdisciplinary approach is not for everyone, and some question its value. Many researchers would prefer to spend their time at the telescope, in the lab, with their modeling computers, writing papers — with laser focus on their areas of expertise. NExSS leaders regularly make the point that those decisions are understood and perfectly fine.

But especially in inherently interdisciplinary fields such as exoplanets and astrobiology, the pool of scientists willing to pitch in to advance the community appears to be large and has proven go be quite useful.

(Since I am writing about NExSS, I want to be clear in saying that the program helps support Many Worlds. A second column about NExSS brain-storming about the future of exoplanet and habitability studies will be coming soon. -Marc Kaufman)