A decades-long quest for incontrovertible and complex martian organics — the chemical building blocks of life — is over.

After almost six years of searching, drilling and analyzing on Mars, the Curiosity rover team has conclusively detected three types of naturally-occurring organics that had not been identified before on the planet.

The Mars organics Science paper by NASA’s Jennifer Eigenbrode and much of the rover’s Sample Analysis on Mars (SAM) instrument team was twinned with another paper describing the discovery of a seasonal pattern to the release of the simple organic gas methane on Mars.

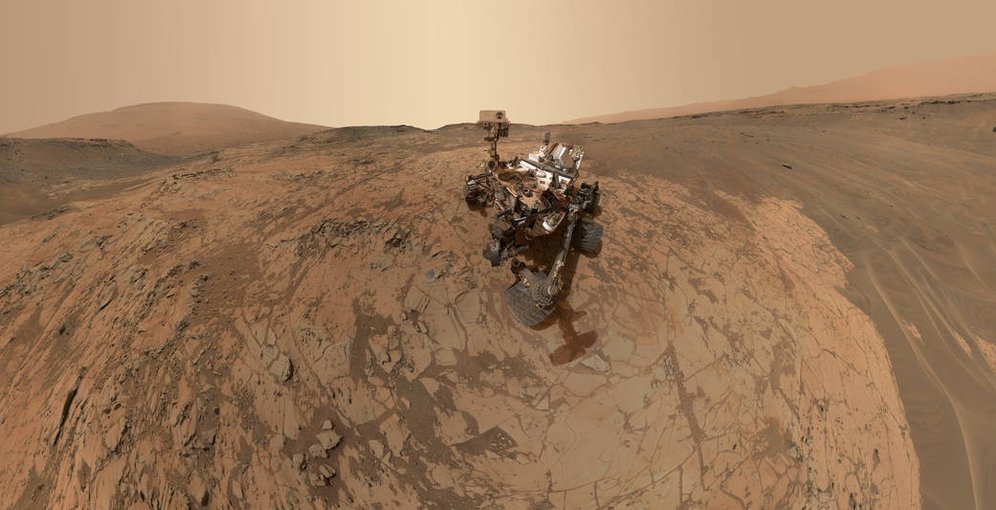

The Curiosity rover on Mars takes a selfie at a site named Mojave. Rock powdered by the rover drill system and then intensively heated rock and then heated to as much as 800 degrees centigrade produced positive findings for long-sought organics.

This finding is also a major step forward not only because it provides ground truth for the difficult question of whether significant amounts of methane are in the martian atmosphere, but equally important it determines that methane concentrations appear to change with the seasons. The implications of that seasonality are intriguing, to say the least.

In an accompanying opinion piece in Science, Inges Loes ten Kate of Utrecht University in Netherlands wrote of the two papers: “Both these findings are breakthroughs in astrobiology.”

The clear conclusion of these (and other) recent findings is that Mars is not a “dead” planet where little ever changes. Rather, it’s one with cycles that appear to produce not only methane but also sporadic surface water and changing dune formations.

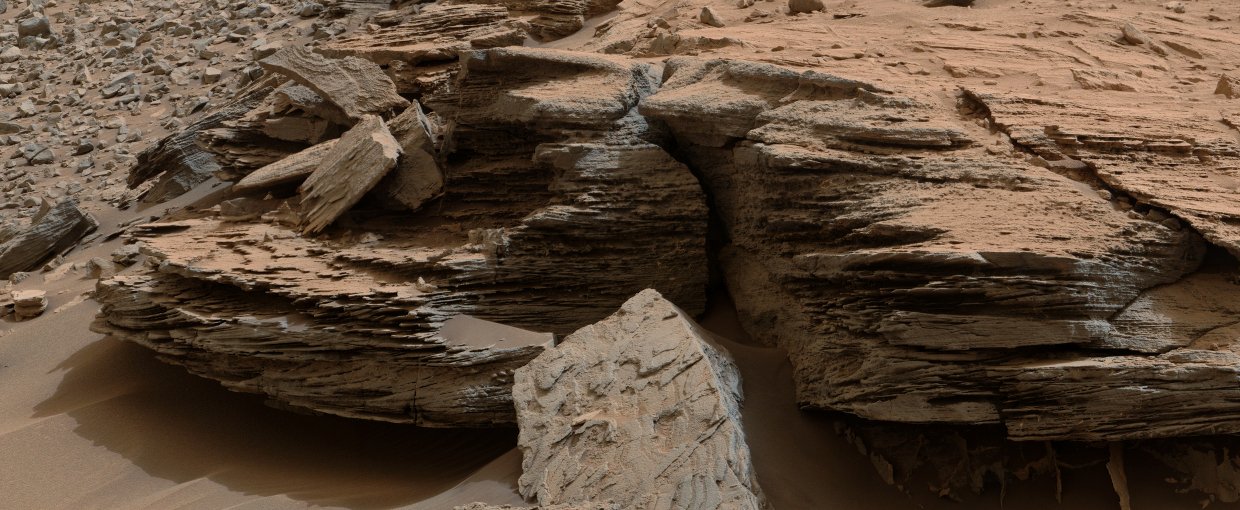

Remains of 3.5 billion-year old lake that once filled Gale Crater. NASA scientists concluded early in the Curiosity mission that the planet was habitable long ago based on the study of mudstone remains like these.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS.

Finding organic compounds on Mars has been a prime goal of the Curiosity rover mission.

Those carbon-based compounds surely fall from the sky on Mars, as they do on Earth and everywhere else, but identifying them has proven illusive.

The consequences of that non-discovery have been significant. Going back to the Viking missions of 1976, scientists concluded that life was not possible on Mars because there were no organics, or none that were detected.

But the reasons for the disappearing organics are pretty well understood. Without much of an atmosphere to protect it, the martian surface is bombarded with ultraviolet radiation, which can destroy organic compounds. Or, in the case of the samples discovered by the SAM team, large organic macromolecules — the likes of proteins, membranes and DNA — are broken up into much smaller pieces.

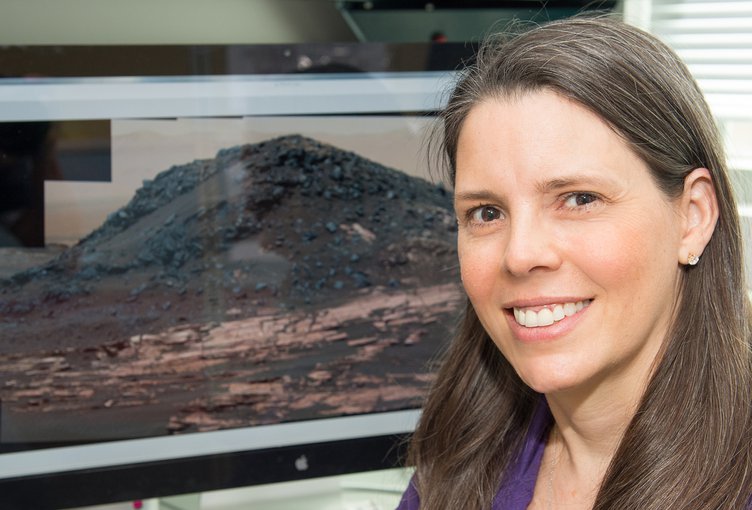

Jen Eigenbrode, research astrobiologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.Image credit: NASA/W. Hrybyk.

The organics, extracted from mudstone at the Mojave and Confidence Hill sites, had bonded tightly with ancient non-organic material. The organic material was freed to be collected as gas only after being exposed to temperatures of more than 500 to 800 centigrade in the SAM oven.

“This material was buried for billions of years and then exposed to extreme surface conditions, so there’s a limit to what we can learn about. Did it come from life? We don’t know.

“But the fact we found the organic carbon adds to the habitability equation. It was in a lake environment that we know could have supported life. Organics are things that organisms can eat.”

It will take different kinds of instruments and samples from drilling deeper into the extreme martian surface to answer the question of whether the organics came from living microbes. But for Eigenbrode, future answers of either “yes” or “no” are almost equally interesting.

Finding clear signs of early martian life would certainly be hugely important, she said. But a conclusion that Mars never had life — although it had conditions some 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago quite similar to conditions on Earth at that time — raises the obvious question of “why not?”

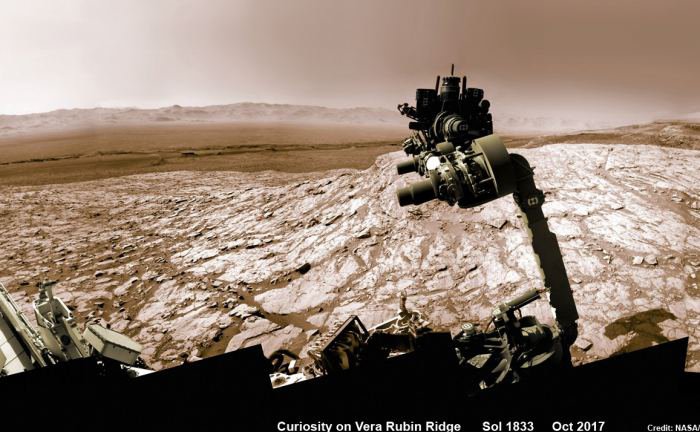

NASA’s Curiosity rover raised robotic arm with drill pointed skyward while exploring Vera Rubin Ridge at the base of Mount Sharp inside Gale Crater. This navcam camera mosaic was stitched from raw images taken on Sol 1833, Oct. 2, 2017 and colorized.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ken Kremer, Marco Di Lorenzo.

Organic molecules are the building blocks of all known life on Earth, and consist of a wide variety of molecules made primarily of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. However, organic molecules can also be made by chemical reactions that don’t involve life.

Examples of non-biological sources include chemical reactions in water at ancient martian hot springs or delivery of organic material to Mars by interplanetary dust or fragments of asteroids and comets.

It needs to be said that today’s Mars organics announcement was not the first we have heard. In 2014, a NASA team reported the presence of chlorine-based organics in Sheepbed mudstone at Yellowknife Bay, the first ancient Mars lake visited by Curiosity.

That work, led by NASA Goddard scientists Caroline Freissinet and Daniel Glavin and published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, focused on signatures from unusual organics not seen naturally on Earth.

The organics were complex and made entirely of martian components, the paper reported. But because they combined chlorine with the organic hydrocarbons, they are not considered to be as “natural” as the discovery announced today.

And when it comes to organics on Mars, the complicated history of research into the presence of the gas methane (a simple molecule that consists of carbon and hydrogen) also shows the great challenges involved in making these measurements on Mars.

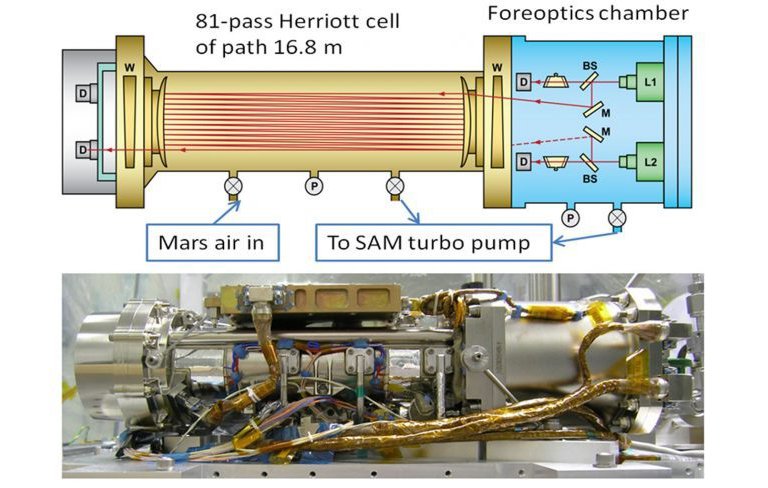

By measuring absorption of light at specific wavelengths, the tunable laser spectrometer on Curiosity measures concentrations of methane, carbon dioxide and water vapor in the Martian atmosphere.Image credit: NASA.

The gold-plated Sample Analysis on Mars contains three instruments that make the measurements of organics and methane.Image credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

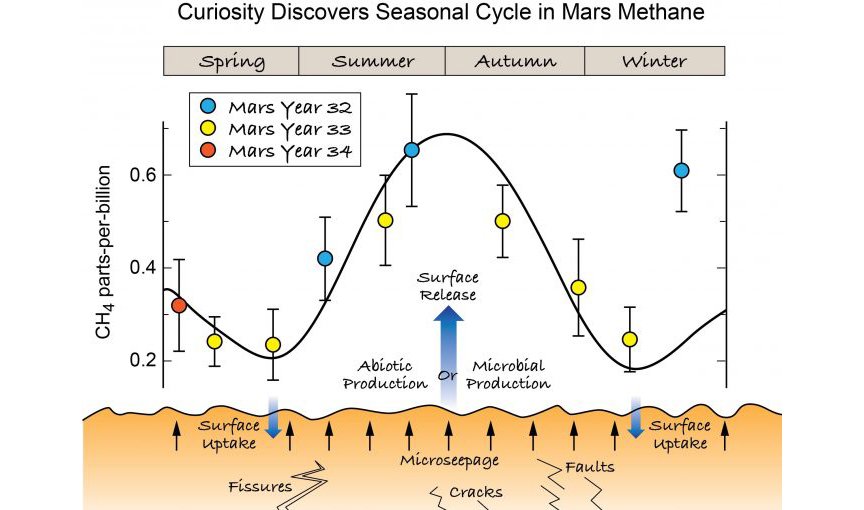

The second Science paper, authored by Chris Webster of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and colleagues, reports that the gas methane has been detected regularly in recent years, with surprising seasonality.

“The history of Mars methane has been frustrating, with reports of some large plumes and spikes detected, but none have been repeatable. It’s almost like they’re random,” he told me. “But now we can see a large seasonal cycle in the background of these detections, and that’s extremely important.”

Over three Mars years, or almost five Earth years, Webster said there have been significant increases in methane detected during the summer, and especially the late summer. That tripling of the methane counts is considered too great to be random, especially since the count declines as predicted after the summer ends.

No definite explanation of why this happens has emerged yet, but one theory has been embraced by some scientists.

While it is still cold in the martian summer, it can get warm enough where the sun shines directly on a collection of ice for some melting to occur. And that melting, the paper reports, could provide an escape valve for methane collected long ago under the surface. The process is termed “microseepage.”

This illustration shows the ways in which methane from the subsurface might find its way to the

surface where its release could produce the large seasonal variation in the atmosphere

as observed by Curiosity. Potential methane sources include byproducts from organisms alive or long dead, ultraviolet degradation of organics, or water-rock chemistry; and its losses include atmospheric photochemistry and surface reactions. Seasons refer to the northern hemisphere. The plotted data is from Curiosity’s TLS-SAM instrument, and the curved line through the data is to aid the eye.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Methane is a crucial organic in astrobiology because most of that gas found on Earth comes from biology, although various non-biological processes can produce methane as well.

Today’s paper by Webster et al is the third in Science on Mars methane as measured by Curiosity, and it is the first to find a seasonal pattern. The first paper, in 2013, actually reported there was no methane measured in early runs, a conclusion that led to push-back from many of those working in the field.

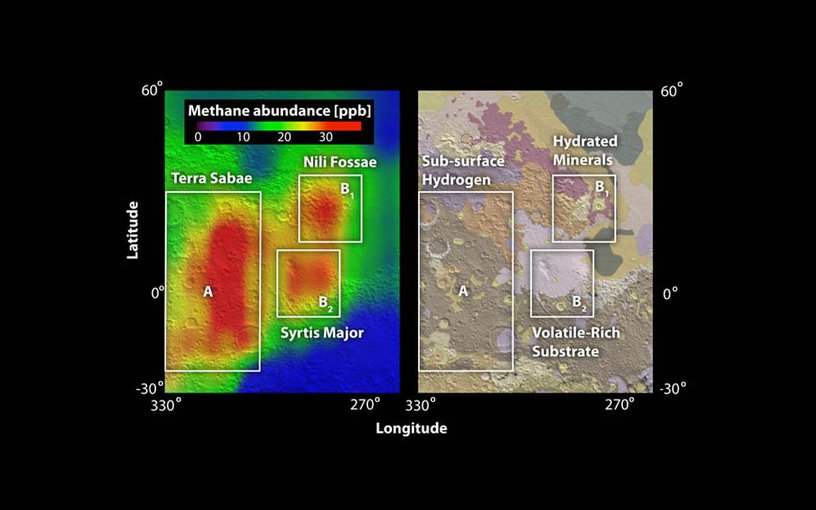

While the Mars methane results released today are being described as a “breakthrough,” they follow closely the findings of a Science paper in 2009 by Michael Mumma and Geronimo Villanueva, both at NASA Goddard.

The two reported then similar findings of plumes of methane on Mars, of a seasonality associated with their distribution, and a similar conclusion that the methane probably was coming from subsurface reservoirs. Like Webster et al, Mumma and Villanueva said they were unable to determine if the source of methane was biological or geological.

The methane levels in the plumes they found were considerably higher than detected so far by Curiosity, but what they were detecting was quite different. Using ground-based telescopes, they detected the high concentrations in two specific areas over a number of years, while Curiosity is measuring methane levels that are more global or regional.

Red areas indicate where in 2003 ground-based observers detected concentrations of methane in the Martian atmosphere, measured in parts per billion (ppb)Image credit: NASA / M. Mumma et. al. (2003).

Just as Webster was criticized for his initial paper saying there was no methane detected on Mars, the Mumma team also got sharp questions about their methodology and conclusions. This grew as their numerous follow-up efforts to detect the Mars methane proved unsuccessful.

But now Webster says the Curiosity findings have essentially “confirmed” what Mumma and Villanueva reported nine years ago.

Still, the Curiosity results are a breakthrough because they were made on Mars rather than through a telescope. Mumma, who described the new Curiosity results as “satisfying,” agreed that they were a major step forward.

“This is how science works,” he said. “We do our work and put out our papers and other scientists react. We take it all in and make changes if needed. But the big changes come when new, and maybe different, data is presented.”

And that’s exactly what will be happening soon regarding methane on Mars. Beginning early this year, the European/Russian Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) has been collecting data specifically on Mars gases including methane. Unlike previous Mars methane campaigns, this one can potentially determine whether the methane being released from below the surface was formed by biology or geology — although not without great difficulty.

Mumma, who is part of that TGO team, said the first release of information is due in the fall.