Nov. 18, 2016

Feature Story

Waiting on Enceladus

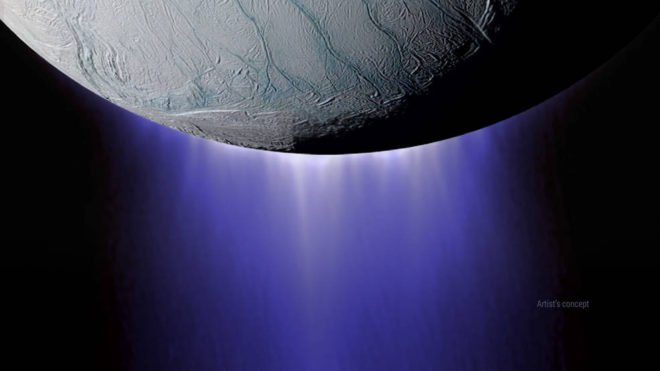

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft completed its deepest-ever dive through the icy plume of Enceladus on Oct. 28, 2015. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Of all the possible life-beyond-Earth questions hanging fire, few are quite so intriguing as those surrounding the now famous plumes of the moon Enceladus: What telltale molecules are in the constantly escaping jets of water vapor, and what dynamics inside the moon are pushing them out?

Seldom, if ever before, have scientists been given such an opportunity to investigate the insides of a potentially habitable celestial body from the outside.

The Cassini mission to Saturn made its closest to the surface (and last) plume fly-through a year ago, taking measurements that the team initially said they would report on within a few weeks.

That was later updated by NASA to include this guidance: Given the important astrobiology implications of these observations, the scientists caution that it will be several months before they are ready to present their detailed findings.

The reference to “important astrobiology implications” certainly could cover some incremental advance, but it does seem to at least hint of something more.

I recently contacted the Jet Propulsion Lab for an update on the fly-through results and learned that a paper has been submitted to the journal Nature and that it will hopefully be accepted and made public in the not-too-distant future.

All this sounds most interesting but not because of any secret finding of life — as some might infer from that official language. Cassini does not have the capacity to make such a detection, and there is no indication at this point that identifiable byproducts of life are present in the plumes.

What is intriguing is that the fly-through was only 30 miles above the moon’s surface — the closest pass through a plume ever by Cassini — and so presumably its instruments produced some new and significant findings.

The scientists writing the paper could not, of course, discuss their findings before publication. But Jonathan Lunine, a Cornell University planetary scientist and physicist on the Cassini mission with a long deep interest in Enceladus, was comfortable discussing what is known about the moon and what Cassini (and future missions) still have to explain.

And thanks to that briefing, it became apparent that whatever new findings are coming, they will not make or break the case for the moon as a habitable place. Rather, they will essentially add to a strong case that has already been made.