Oct. 18, 2018

Feature Story

Technosignatures and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

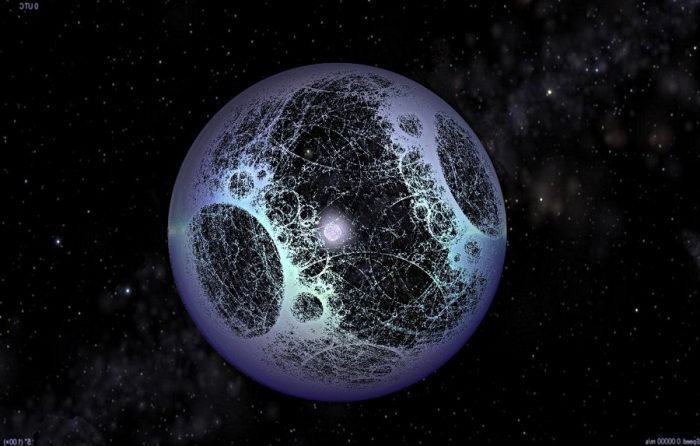

A rendering of a potential Dyson sphere, named after Freeman A. Dyson. As proposed by the physicist and astromomer decades ago, they would collect solar energy on a solar system wide scale for highly advanced civilizations.Image credit: SentientDevelopments.com.

The word “SETI” pretty much brings to mind the search for radio signals come from distant planets, the movie “Contact,” Jill Tarter, Frank Drake and perhaps the SETI Institute, where the effort lives and breathes.

But there was a time when SETI — the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence — was a significantly broader concept, that brought in other ways to look for intelligent life beyond Earth.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s — a time of great interest in UFOs, flying saucers and the like — scientists not only came up with the idea of searching for distant intelligent life via unnatural radio signals, but also by looking for signs of unexpectedly elevated heat signatures and for optical anomalies in the night sky.

The history of this search has seen many sharp turns, with radio SETI at one time embraced by NASA, subsequently de-funded because of congressional opposition, and then developed into a privately and philanthropically funded project of rigor and breadth at the SETI Institute. The other modes of SETI went pretty much underground and SETI became synonymous with radio searches for ET life.

But this history may be about to take another sharp turn as some in Congress and NASA have become increasingly interested in what are now called “technosignatures,” potentially detectable signatures and signals of the presence of distant advanced civilizations. Technosignatures are a subset of the larger and far more mature search for biosignatures — evidence of microbial or other primitive life that might exist on some of the billions of exoplanets we now know exist.

And as a sign of this renewed interest, a technosignatures conference was scheduled by NASA at the request of Congress (and especially retiring Republican Rep. Lamar Smith of Texas.) The conference took place in Houston late last month, and it was most interesting in terms of the new and increasingly sophisticated ideas being explored by scientists involved with broad-based SETI.

“There has been no SETI conference this big and this good in a very long time,” said Jason Wright, an astrophysicist and professor at Pennsylvania State University and chair of the conference’s science organizing committee. “We’re trying to rebuild the larger SETI community, and this was a good start.”

At this point, the search for technosignatures is often likened to that looking for a needle in a haystack. But what scientists are trying to do is define their haystack, determine its essential characteristics, and learn how to best explore it.Image credit: Wiki Commons.

During the three day meeting in Houston, scientists and interested private and philanthropic reps. heard talks that ranged from the trials and possibilities of traditional radio SETI to quasi philosophical discussions about what potentially detectable planetary transformations and by-products might be signs of an advanced civilization. (An agenda and videos of the talks are here.)

The subjects ranged from surveying the sky for potential millisecond infrared emissions from distant planets that could be purposeful signals, to how the presence of certain unnatural, pollutant chemicals in an exoplanet atmosphere that could be a sign of civilization. From the search for thermal signatures coming from megacities or other by-products of technological activity, to the possible presence of “megastructures” built to collect a star’s energy by highly evolved beings.

All but the near infrared SETI are for the distant future — or perhaps are on the science fiction side — but astronomy and the search for distant life do tend to move forward slowly. Theory and inference most often coming well before observation and detection.

So thinking about the basic questions about what scientists might be looking for, Wright said, is an essential part of the process.

Indeed, it is precisely what Michael New, Deputy Associate Administrator for Research within NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, told the conference.

He said that he, NASA and Congress wanted the broad sweep of ideas and research out there regarding technosignatures, from the current state of the field to potential near-term findings, and known limitations and possibilities.

“The time is really ripe scientifically for revisiting the ideas of technosignatures and how to search for them,” he said.

He offered the promise of NASA help (admittedly depending to some extent on what Congress and the administration decide) for research into new surveys, new technologies, data-mining algorithms, theories and modelling to advance the hunt for technosignatures.

Crew members aboard the International Space Station took this nighttime photograph of much of the Atlantic coast of the United States.Image credit: NASA.

Among the several dozen scientists who discussed potential signals to search for were the astronomer Jill Tarter, former director of the Center for SETI Research, Planetary Science Institute astrobiologist David Grinspoon and University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank. They all looked at the big picture, what artifacts in atmospheres, on surfaces and perhaps in space that advanced civilizations would likely produce by dint of their being “advanced.”

All spoke of the harvesting of energy to perform work as a defining feature of a technological planet, with that “work” describing transportation, construction, manufacturing and more.

Beings that have reached the high level of, in Frank’s words, exo-civilization produce heat, pollutants, changes to their planets and surroundings in the process of doing that work. And so a detection of highly unusual atmospheric, thermal, surface and orbital conditions could be a signal.

One example mentioned by several speakers is the family of chemical chloroflourohydrocarbons (CFCs,) which are used as commercial refrigerants, propellants and solvents.

MeerKAT, originally the Karoo Array Telescope, is a radio telescope consisting of 64 antennas now being tested and verified in the Northern Cape of South Africa.Image credit: South African Radio Astronomy Observatory.

These CFCs are a hazardous and unnatural pollutant on Earth because they destroy the ozone layer, and they could be doing something similar on an exoplanet. And as described in the conference, the James Webb Space Telescope — once it’s launch and working — could most likely detect such an atmospheric compound if it’s in high concentration and the project was given sufficient telescope time.

A similar single finding described by Tarter that could be revolutionary is the radioactive isotope tritium, which is a by-product of the nuclear fusion process. It has a short half-life and so any distant discovery would point to a recent use of nuclear energy (as long as it’s not associated with a recent supernova event, which can also produce tritium.)

But there many other less precise ideas put forward.

Glints on the surface of planets could be the product of technology, as might be weather on an exoplanet that has been extremely well stabilized, modified planetary orbits and chemical disequilibriums in the atmosphere based on the by-products of life and work. (These disequilibriums are a well-established feature of biosignature research, but Frank presented the idea of a technosphere which would process energy and create by-products at a greater level than its supporting biosphere.)

Another unlikely but most interesting example of a possible technosignature put forward by Tarter and Grinspoon involved the seven planets of the Trappist-1 solar system, all tidally locked and so lit on only one side. She said that they could potentially be found to be remarkably similar in their basic structure, alignment and dynamics. As Tarter suggested, this could be a sign of highly advanced solar engineering.

This is exciting – the next phase Square kilometer Array (SKA2) will be able to detect Earth-level radio leakage from nearby stars.Image credit: South African Radio Astronomy Observatory.

Grinspoon seconded that notion about Trappist-1, but in a somewhat different context.

He has worked a great deal on the question of today’s anthroprocene era — when humans actively change the planet — and he expanded on his thinking about Earth into the galaxies.

Grinspoon said that he had just come back from Japan, where he had visited Hiroshima and its atomic bomb sites, and came away with doubts that we were the “intelligent” civilization we often describe ourselves in SETI terms. A civilization that may well self destruct — a fate he sees as potentially common throughout the cosmos — might be considered “proto-intelligent,” but not smart enough to keep the civilization going over a long time.

Projecting that into the cosmos, Grinspoon argued that there may well be many such doomed civilizations, and then perhaps a far smaller number of those civilizations that make it through the biological-technological bottleneck that we seem to be facing in the centuries ahead.

These civilizations, which he calls semi-immortal, would develop inherently sustainable methods of continuing, including modifying major climate cycles, developing highly sophisticated radars and other tools for mitigating risks, terraforming nearby planets, and even finding ways to evolve the planet as its place in the habitable zone of its host star becomes threatened by the brightening or dulling of that star.

The trick to trying to find such truly evolved civilizations, he said, would be to look for technosignatures that reflect anomalous stability and not rampant growth. In the larger sense, these civilizations would have integrated themselves into the functioning of the planet, just as oxygen, first primitive and then complex life integrated themselves into the essential systems of Earth.

And returning to the technological civilizations that don’t survive, they could produce physical artifacts that now permeate the galaxy.

The NIROSETI team with their new infrared detector inside the dome at Lick Observatory. Left to right: Remington Stone, Dan Wertheimer, Jérome Maire, Shelley Wright, Patrick Dorval and Richard Treffers.Image credit: Laurie Hatch.

While the conference focused on technosignature theory, models, and distant possibilities, news was also shared about two concrete developments involving research today.

The first involved the radio telescope array in South Africa now called MeerKAT, a prototype of sorts that will eventually become the gigantic Square Kilometer Array.

Breakthrough Listen, the global initiative to seek signs of intelligent life in the universe, would soon announce the commencement of a major new program with the MeerKAT telescope, in partnership with the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO).

Breakthrough Listen’s MeerKAT survey will examine a million individual stars – 1,000 times the number of targets in any previous search – in the quietest part of the radio spectrum, monitoring for signs of extraterrestrial technology. With the addition of MeerKAT’s observations to its existing surveys, Listen will operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in parallel with other surveys.

This clearly has the possibility of greatly expanded the amount of SETI listening being done. The SETI Institute, with its radio astronomy array in northern California and various partners, have been listening for almost 60 years, without detecting a signal from our galaxy.

That might seem like a disappointing intimation that nothing or nobody else is out there, but not if you listen to Tarter explain how much listening has actually been done. Almost ten years ago, she calculated that if the Milky Way galaxy and everything in it was an ocean, then SETI would have listened to a cup full of water from that ocean. Jason Wright and his students did an updated calculation recently, and now the radio listening amounts to a small swimming pool within that enormous ocean.

Participants in the technosignatures conference in Houston last month, the largest SETI gathering in years. And this one was sponsored by NASA and put together by the NExSS for Exoplanet Systems Science (NExSS,) an interdisciplinary agency initiative.Image credit: Delia Enriquez.

The other news came from Shelley Wright of the University of California, San Diego, who has been working on an optical SETI instrument for the Lick Observatory.

The Near-Infrared Optical SETI (NIROSETI) instrument she and her colleagues have developed is the first instrument of its kind designed to search for signals from extraterrestrials at near-Infrared wavelengths. The near-infrared regime is an excellenr spectral region to search for signals from extraterrestrials, since it offers a unique window for interstellar communication.

The NIROSETI instrument utilizes two near-infrared photodiodes to be able to detect artificial, very fast (nanosecond) pulses of infrared radiation.

The NIROSETI instrument, which is mounted on the Nickel telescope at Lick Observatory, splits the incoming near-infrared light onto two channels, and then checks for coincident events, which indicate signals that are identified by both detectors simultaneously.

Wright of Penn State was especially impressed by the project, which he said can look at much of the sky at once and was put together with on very limited budget.

Wright, who teaches a course on SETI at Penn State and is a co-author of a recent paper trying to formalize SETI terminology, said his own take-away from the conference is that it may well represent an important and positive moment in the history of technosignatures.

“Without NASA support, the whole field has lacked the normal structure by which astronomy advances,” he said. “No teaching of the subject, no standard terms, no textbook to formalize findings and understandings.

“The Seti Institiute carried us through the dark times, and they did that outside of normal, formal structures. The Institute remains essential, but hopefully that reflex identification will start to change.”