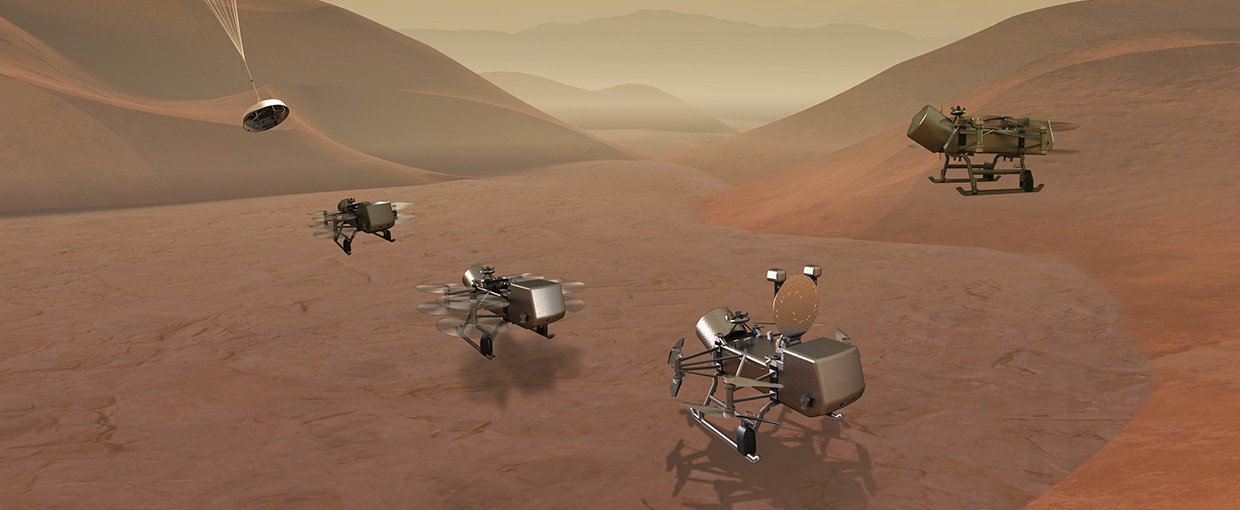

The Dragonfly drone has been selected as the next New Frontiers mission, this time to Saturn’s moon Titan. Animation of the vehicle taking off from the surface of the moon.Image credit: NASA.

A vehicle that flies like a drone and will try to unravel some of the mysteries of Saturn’s moon Titan was selected yesterday to be the next New Frontiers mission to explore the solar system.

Searching for the building blocks of life, the Dragonfly mission will be able to fly multiple sorties to sample and examine sites around Saturn’s icy moon.

Titan has a thick atmosphere and features a variety of hydrocarbons, with rivers and lakes of methane, ethane and natural gas, as well as and precipitation cycles like on Earth. As a result, Dragonfly has been described as an astrobiology mission because it will search for signs of the prebiotic environments like those on Earth that gave rise to life.

“Titan is unlike any other place in the solar system, and Dragonfly is like no other mission,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science at the agency headquarters in Washington.

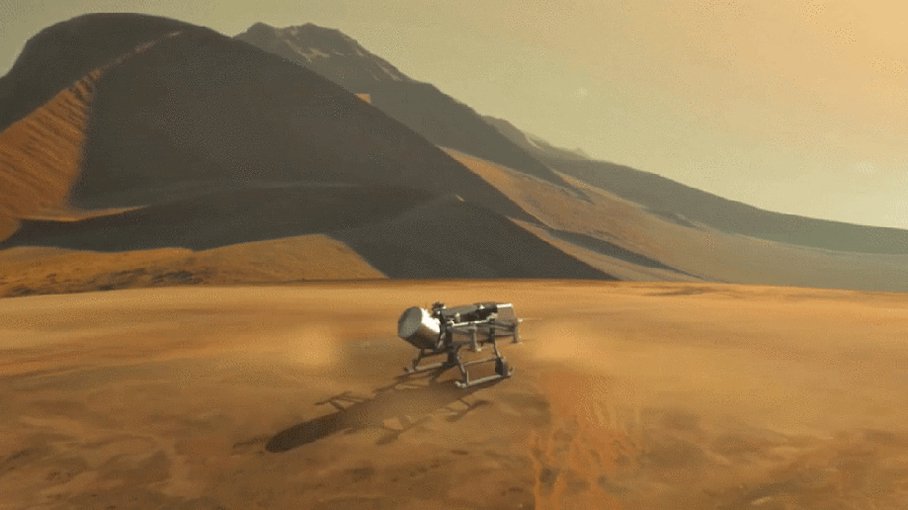

“It’s remarkable to think of this rotorcraft flying miles and miles across the organic sand dunes of Saturn’s largest moon, exploring the processes that shape this extraordinary environment. Dragonfly will visit a world filled with a wide variety of organic compounds, which are the building blocks of life and could teach us about the origin of life itself.”

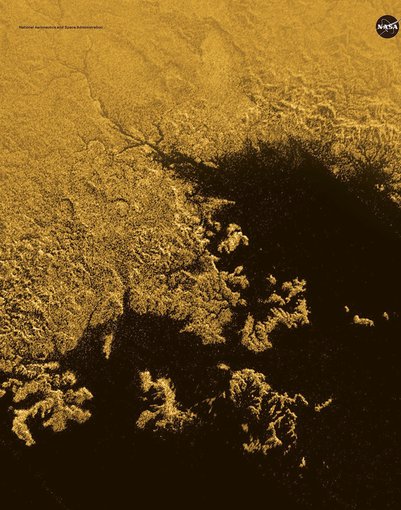

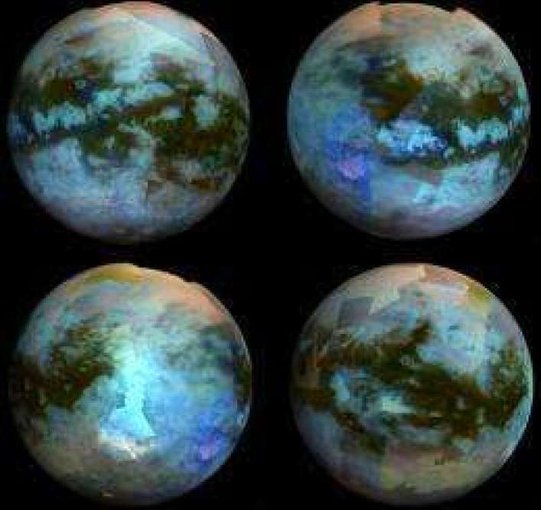

Saturn’s moon Titan is significantly larger than our moon, and larger than the planet Mercury. It features river channels of ethane and methane, and lakes of liquified natural gas. It is the only other celestial body in our solar system that has flowing liquid on its surface.Image credit: NASA.

As described in a NASA release, Titan is an analog to the very early Earth, and can provide clues to how life may have arisen on our planet.

Dragonfly will explore environments ranging from organic dunes to the floor of an impact crater where liquid water and complex organic materials key to life once existed together for possibly tens of thousands of years. Its instruments will study how far prebiotic chemistry may have progressed.

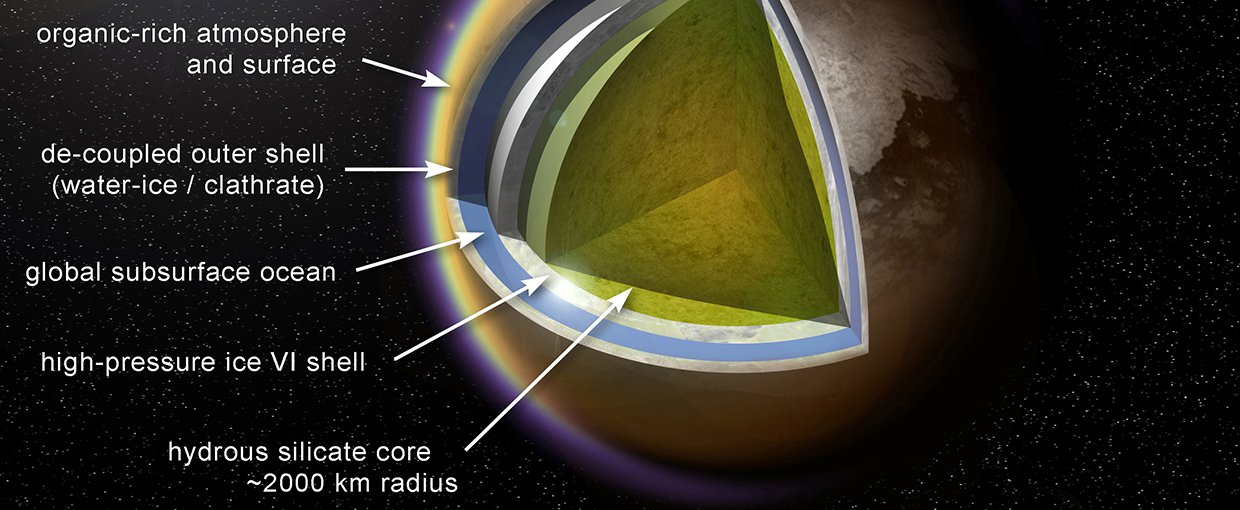

They also will investigate the moon’s atmospheric and surface properties and its subsurface ocean and liquid reservoirs. Additionally, instruments will search for chemical evidence of past or extant life.

Because it is so far from the sun, Titan’s surface temperature is around -290 degrees Fahrenheit and its surface pressure is 50 percent higher than Earth’s.

It is scheduled to launch in 2026 and will arrive at Titan eight years later. It will have a baseline mission of 2.7 years, and will be able to build up to a series of “leapfrog” flights of up to five miles.

If and when it lands, it will not be the first spacecraft to touch down on Titan. The Cassini-Huygens mission — jointly run by NASA and the European Space Agency — included a parachute landing on Titan by Huygens in 2005.

It returned data to Earth for around 90 minutes, using the orbiter as a relay. This was the first landing ever accomplished in the outer solar system and the first landing on a moon other than Earth’s moon.

An international team led by the University of Nantes has pieced together images gathered over six years by the Cassini mission to create a global mosaic of the surface of Titan.Image credit: Stéphane Le Mouélic.

As described by NASA, Dragonfly took advantage of 13 years’ worth of Cassini-Huygens data to choose a calm weather period to land, along with a safe initial landing site and scientifically interesting targets.

It will first land at the equatorial “Shangri-La” dune fields, which are terrestrially similar to the linear dunes in Namibia in southern Africa and offer a diverse sampling location.

Dragonfly will explore this region in short flights, building up to a series of those longer “leapfrog” flights. It will stop along the way to take samples from compelling areas with diverse geography. It will finally reach the Selk impact crater, where there is evidence of past liquid water, organics – the complex molecules that contain carbon, combined with hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen – and energy, which together make up the recipe for life. The lander will eventually fly more than 108 miles – nearly double the distance traveled to date by all the Mars rovers combined.

Titan has a nitrogen-based atmosphere like Earth. Unlike Earth, Titan has clouds and rain of methane. Other organics are formed in the atmosphere and fall like light snow.

The moon’s weather and surface processes have combined complex organics, energy, and water similar to those that may have sparked life on our planet. And so the results will be of great interest to astrobiologists.

Dragonfly Mission Overview Dragonfly mission concept of entry, descent, landing, surface operations, and flight at Titan.Image credit: Johns Hopkins APL.

Dragonfly was selected as part of the agency’s New Frontiers program, which includes the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, Juno to Jupiter, and OSIRIS-REx to the asteroid Bennu. Dragonfly is led by Principal Investigator Elizabeth Turtle, who is based at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. New Frontiers supports missions that have been identified as top solar system exploration priorities by the planetary community. The program is managed by the Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Planetary Science Division in Washington.

“The New Frontiers program has transformed our understanding of the solar system, uncovering the inner structure and composition of Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere, discovering the icy secrets of Pluto’s landscape, revealing mysterious objects in the Kuiper belt, and exploring a near-Earth asteroid for the building blocks of life,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “Now we can add Titan to the list of enigmatic worlds NASA will explore.”