James Lovelock, independent scientist, inventor, and author, who in the early 1960s helped NASA develop life-detection-technologies for lunar and planetary missions, has passed away. He died on July 26, his 103d birthday (due to complications from a fall).

Lovelock was an early recipient of grants from NASA’s Exobiology Program. The Program was established in 1960, under NASA’s Office of Life Sciences. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory recruited Lovelock to work on life detection technology for lunar and planetary missions. Lovelock received his first Exobiology grant in 1961, to develop a gas chromatograph for the Surveyor lunar exploration program. He received a second grant in 1963 to continue this work, and he continued to work with NASA on life detection instrumentation for missions to Mars.

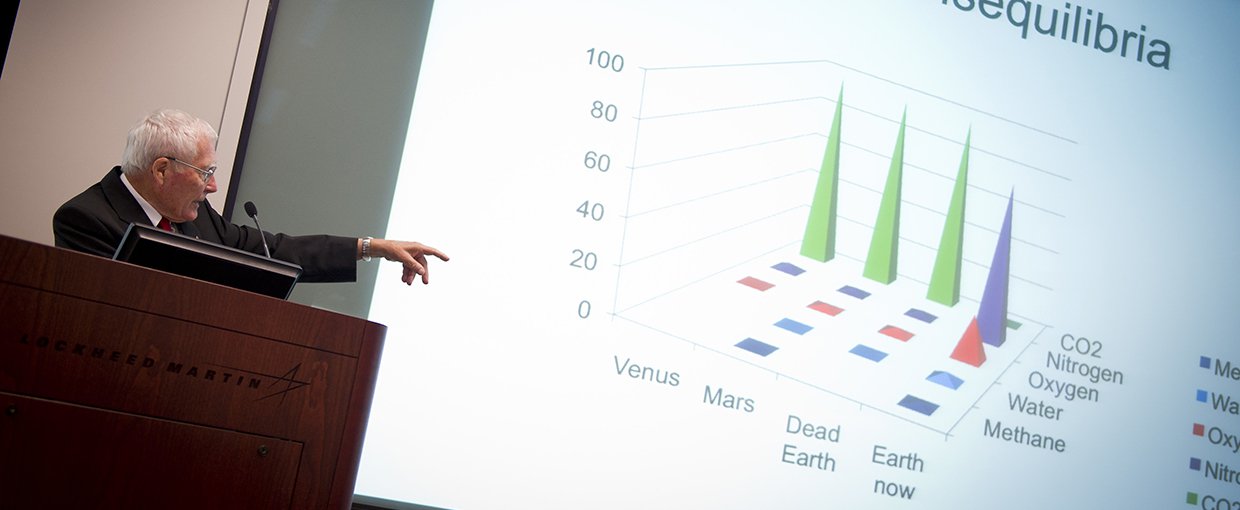

James Lovelock speaking during the “Seeking Signs of Life” Symposium, celebrating 50 Years of Exobiology and Astrobiology at NASA, Thursday, Oct. 14, 2010, at the Lockheed Martin Global Vision Center in Arlington, Va.Image credit: NASA HQ.

“In 1961 I got this incredible letter from NASA asking if I would want to be an experimenter on their first lunar and planetary missions. I had read science fiction since I was a kid so I just couldn’t refuse. It was great fun.”

At a NASA symposium on the history of exobiology and astrobiology in 2010, Lovelock described his last encounter with NASA and JPL, in connection with the Viking landings on Mars in 1976. “I’m the proud possessor of three certificates of recognition from NASA for inventions that made possible the GCMS [gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer] experiment” on the Viking landers. “It gives me a great deal of pride and pleasure to look up into the sky on a clear, clear night and see Mars and know that something of me is sitting there,” he said.

“As one whose childhood was illuminated by the writing of Jules Verne and Olaf Stapledon, I was delighted to have the chance of discussing at first hand the plans for investigating Mars.”

Through his association with origins-of-life researchers funded by Exobiology, Lovelock met Lynn Margulis – the Exobiology Program’s first female principal investigator – and they became collaborators on developing the Gaia hypothesis, proposing that Earth’s biosphere is a self-regulating organism. NASA Exobiology supported Lovelock and Margulis as they worked on Gaia – through a time when some prominent Earth and life scientists were critical of it.

“Lynn and I owe an enormous debt to NASA,” Lovelock said at the symposium, “for having provided us with an opportunity to take a step beyond Darwin and recognize that evolution by natural selection is a property of the whole planet, not just the organisms alone.”

Through their work, the Gaia hypothesis evolved into the Gaia theory, which led to the development of the field called Earth system science. “The work of NASA-funded exobiologists led to the founding of this new discipline, “and perhaps planetary science,” Lovelock said. Gaia has certainly made a significant contribution to scientific understanding of climate change on Earth.

While Lovelock had the demeanor of a kind and gentle soul, his intellect was fierce. The breadth of his knowledge was wide, and the depth of his knowledge was deep. Trained as a bacteriologist (his Ph.D. thesis was on the properties and use of aliphatic and hydroxy carboxylic acids in aerial disinfection), he became known as an instrumentation developer, leading to his recruitment by JPL. The recipient of numerous honorary degrees, awards, and prizes, he remained an independent researcher throughout his career, maintaining a lab at his home in Dorset, England.

Lovelock will be missed by astrobiologists, other scientists, environmentalists, and citizens of the world who are concerned about the state of our planet. His lifetime of work is his legacy.