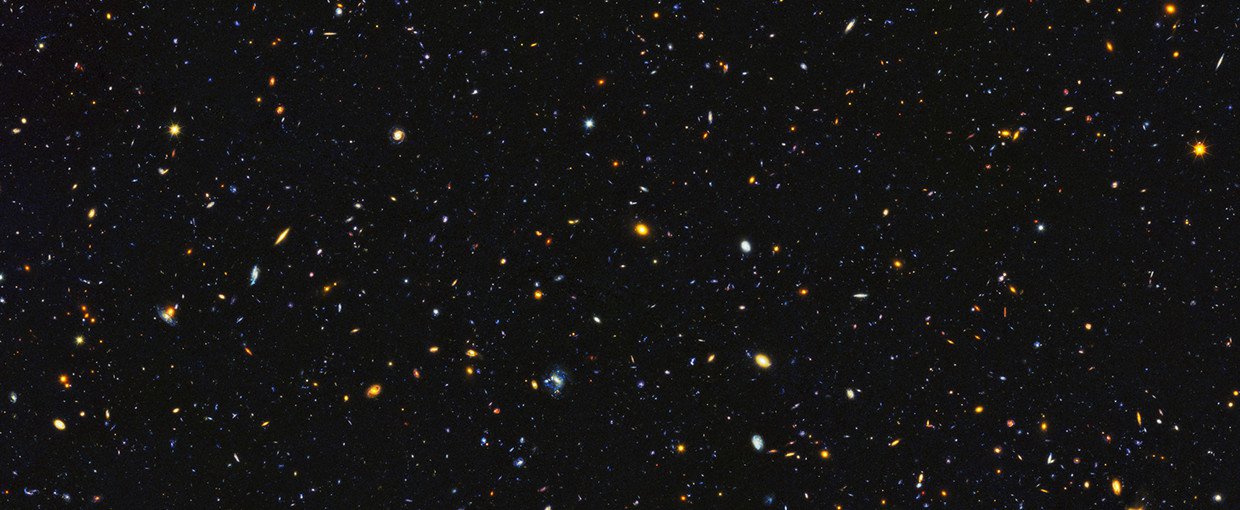

Astronomers have just assembled one of the most comprehensive portraits yet of the Universe’s evolutionary history, based on a broad spectrum of observations by the Hubble Space Telescope and other space and ground-based telescopes. Each of the approximately 15,000 specks and spirals are galaxies, widely distributed in time and space.Image credit: NASA, ESA, P. Oesch of the University of Geneva, and M. Montes of the University of New South Wales.

Here’s an image to fire your imagination: Fifteen thousand galaxies in one picture — sources of light detectable today that were generated as much as 11 billion years ago.

Of those 15,000 galaxies, some 12,000 are inferred to be in the process of forming stars. That’s hardly surprising because the period around 11 billions years ago has been determined to be the prime star-forming period in the history of the universe. That means for the oldest galaxies in the image, we’re seeing light that left its galaxy but three billion years after the Big Bang.

This photo mosaic, put together from images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and other space and ground-based telescopes, does not capture the earliest galaxies detected. That designation belongs to a galaxy found in 2016 that was 420 million years old at the time it sent out the photons just collected. (Photo below.)

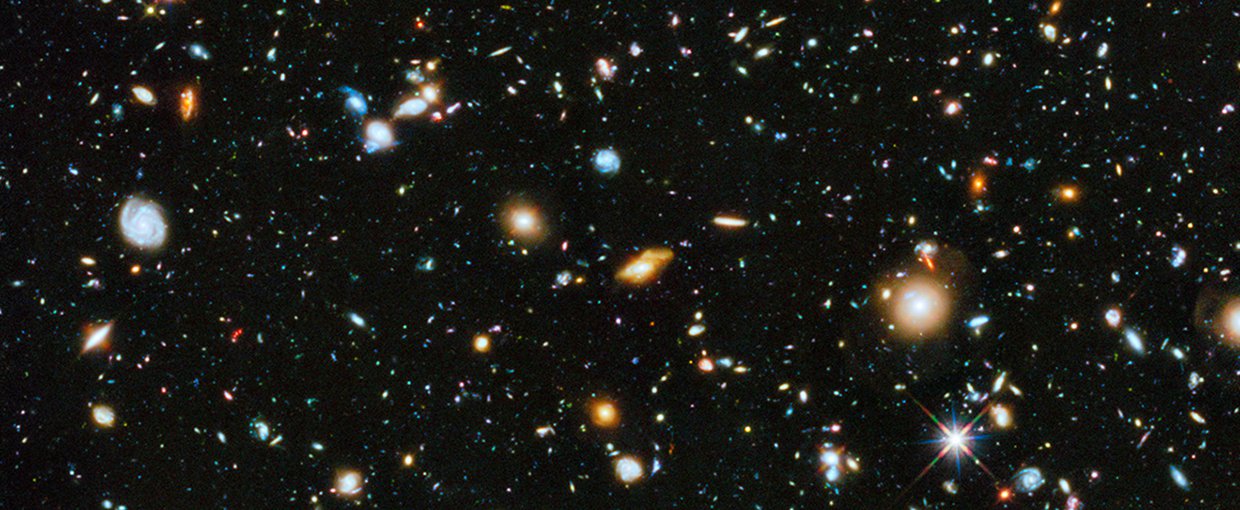

Nor is it quite as visually dramatic as the iconic Ultra Deep Field image produced by NASA in 2014. (Photo below as well.)

But this image is one of the most comprehensive yet of the history of the evolution of the universe, presenting galaxy light coming to us over a timeline up to those 11 billion years. The image was released last week by NASA and supports an earlier paper in The Astrophysical Journal by Pascal Oesch of Geneva University and a large team of others.

And it shows, yet again, the incomprehensible vastness of the forest in which we are a tiny leaf.

Some people apparently find our physical insignificance in the universe to be unsettling. I find it mind-opening and thrilling — that we now have the capability to not only speculate about our place in this enormity, but to begin to understand it as well.

The Ultra-Deep field composite, which contains approximately 10,000 galaxies. The images were collected over a nine-year period.Image credit: NASA, ESA, H. Teplitz and M. Rafelski (IPAC/Caltech), A. Koekemoer (STScI), R. Windhorst (Arizona State University), and Z. Levay (STScI).

For those unsettled by the first image, here is the 2014 Ultra Deep Field image, which is 1/14 times the area of the newest image. More of the shapes in this photo look to our eyes like they could be galaxies, but those in the first image are essentially the same.

In both images, astronomers used the ultraviolet capabilities of the Hubble, which is now in its 28th year of operation.

Because Earth’s atmosphere filters out much ultraviolet light, the space-based Hubble has a huge advantage because it can avoid that diminishing of ultraviolet light and provide the most sensitive ultraviolet observations possible.

That capability, combined with infrared and visible-light data from Hubble and other space and ground-based telescopes, allows astronomers to assemble these ultra deep space images and to gain a better understanding of how nearby galaxies grew from small clumps of hot, young stars long ago.

The light from distant star-forming regions in remote galaxies started out as ultraviolet. However, the expansion of the universe has shifted the light into infrared wavelengths.

These images, then, straddle the gap between the very distant galaxies, which can only be viewed in infrared light, and closer galaxies which can be seen across a broad spectrum of wavelengths.

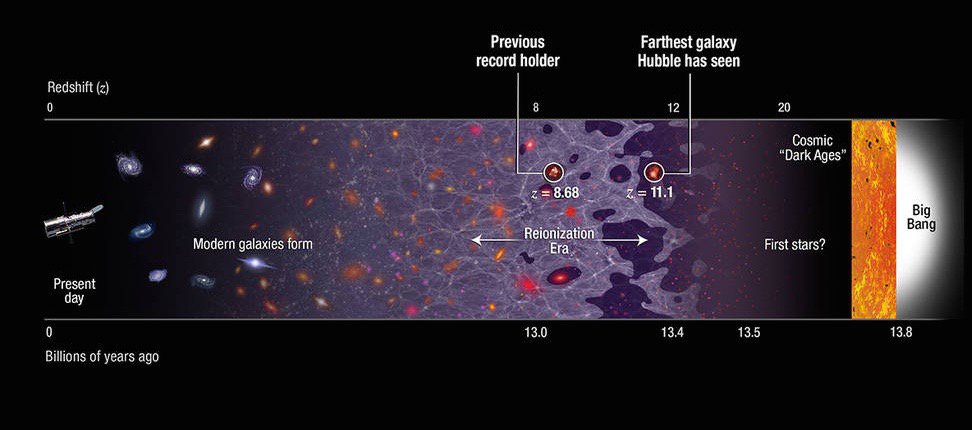

The farthest away galaxy discovered so far is called GN-z11 and is seen now as it was 13.4 billion years in the past. That’s just 400 million years after the Big Bang.

GN-z11 is surprisingly bright infant galaxy located in the direction of the constellation of Ursa Major.

The farthest away galaxy ever detected — GN-z11.Image credit: NASA, ESA, P. Oesch (Yale University, Geneva University), G. Brammer (STScI), P. van Dokkum (Yale University), and G. Illingworth (University of California, Santa Cruz).

In addition representing cutting-edge science — and enabling much more — these looks into the most distant cosmic past offer a taste of what the James Webb Space Telescope, now scheduled to launch in 2021, is designed to explore. It will have greatly enhanced capabilities to explore in the infrared, which will advance ultra-deep space observing.

But putting aside the cosmic mysteries that ultra deep space and time astronomy can potentially solve, the images available today from Hubble and other telescopes are already more than enough to fire the imagination about what is out there and what might have been out there some millions or billions of years ago.

Galaxy formation chronology, showing GN-z11 in context. Hubble spectroscopically confirmed the farthest away galaxy to date.Image credit: NASA, ESA, P. Oesch and B. Robertson (University of California, Santa Cruz), and A. Feild (STScI).

A consensus of exoplanet scientists holds that each star in the Milky Way galaxy is likely to have at least one planet circling it, and our galaxy alone has billions and billions of stars. That makes for a lot of planets that just might orbit at the right distance from its host star to support life and potentially have atmospheric, surface and subsurface conditions that would be supportive as well.

A look these deep space images raises the question of how many of them also house stars with orbiting planets, and the answer is probably many of them. All the exoplanets identified so far are in the Milky Way, except for one set of four so far.

Their discovery was reported earlier this year by Xinyu Dai, an astronomer at the University of Oklahoma, and his co-author, Eduardo Guerras. They came across what they report are planets while using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to study the environment around a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy located 3.8 billion light-years away from Earth.

In The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the authors report the galaxy is home to a quasar, an extremely bright source of light thought to be created when a very large black hole accelerates material around it. But the researchers said the results of their study indicated the presence of planets in a galaxy that lies between Earth and the quasar.

Furthermore, the scientists said results suggest that in most galaxies there are hundreds of free-floating planets for every star, in addition to those which might orbit a star.

The takeaway for me, as someone who has long reported on astrobiology and exoplanets, is that it is highly improbable that there are no other planets out there where life occurs, or once occurred.

As these images make clear, the number of planets that exist or have existed in the universe is essentially infinite. That no others harbor life seems near impossible.