April 10, 2017

Feature Story

What Scientists Expect to Learn From Cassini’s Upcoming Plunge Into Saturn

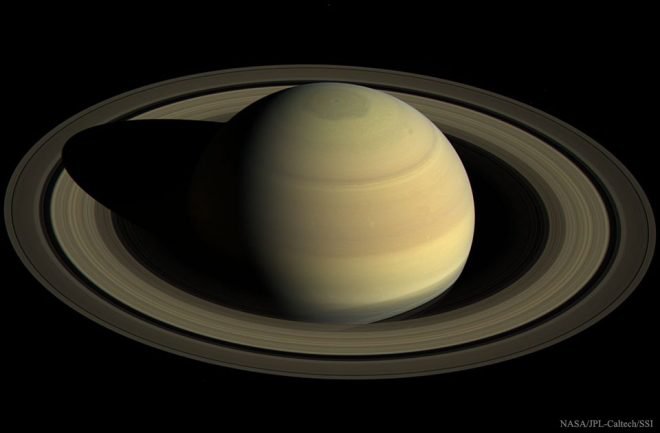

Saturn as imaged from above by Cassini last year. Over the next five months, the spacecraft will orbit closer and closer to the planet and will finally plunge into its atmosphere. (NASA)

Seldom has the planned end of a NASA mission brought so much expectation and scientific high drama.

The Cassini mission to Saturn has already been a huge success, sending back iconic images and breakthrough science of the planet and its system. Included in the haul have been the discovery of plumes of water vapor spurting from the moon Encedalus and the detection of liquid methane seas on Titan. But as members of the Cassini science team tell it, the end of the 13-year mission at Saturn may well be its most scientifically productive time.

Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) put it this way: “Cassini will make some of its most extraordinary observations at the end of its long life.”

This news was first announced last week, but I thought it would be useful to go back to the story to learn more about what “extraordinary” science might be coming our way, with the help of Spilker and NASA headquarters Cassini program scientist Curt Niebur.

And the very up close encounters with Saturn’s rings and its upper atmosphere — where Cassini is expected to ultimately lose contact with Earth — certainly do offer a trove of scientific riches about the basic composition and workings of the planet, as well as the long-debated age and origin of the rings. What’s more, everything we learn about Saturn will have implications for, and offer insights into, the vast menagerie of gas giant exoplanets out there.

“The science potential here is just huge,” Niebur told me. “I could easily conceive of a billion dollar mission for the science we’ll get from the grand finale alone.”

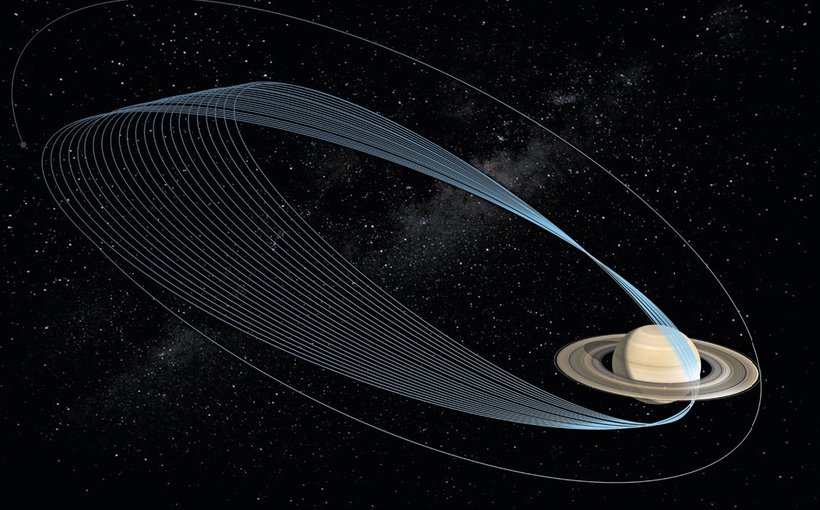

The Cassini spacecraft will make 22 increasingly tight orbits of Saturn before it disappears into the planet’s atmosphere in mid-September, as shown in this artist rendering. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The 20-year, $3.26 billion Cassini mission, a collaboration of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, is coming to an end because the spacecraft will soon run out of fuel. The agency could have just waited for that moment and let the spacecraft drift off into space, but decided instead on the taking the big plunge.

This was considered a better choice not only because of those expected scientific returns, but also because letting the dead spacecraft drift meant that theoretically it could be pulled towards Titan or Enceladus — moons that researchers now believe just might support life.

Although the spacecraft was sterilized before launch, scientists didn’t want to take the chance that some bacteria might remain in the capsule that could possibly contaminate the moons with life from Earth.

So instead Cassini will be sent on 22 closer and closer passes around Saturn, into the region between the innermost ring and the atmosphere where no spacecraft has ever gone. On April 26, Cassini will make the first of those dives through a 1,500-mile-wide gap between Saturn and its rings as part of the mission’s grand finale.

As it makes those terminal orbits, the spacecraft will have to be maneuvered with precision so it doesn’t actually fly into one of the rings. They consist of water ice, small meteorites and dust, and are sufficiently dense to fatally damage Cassini.

“Based on our best models, we expect the gap to be clear of particles large enough to damage the spacecraft. But we’re also being cautious by using our large antenna as a shield on the first pass, as we determine whether it’s safe to expose the science instruments to that environment on future passes,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab. “Certainly there are some unknowns, but that’s one of the reasons we’re doing this kind of daring exploration at the end of the mission.”

Then in mid-September, following a distant encounter with Titan and its gravity, the spacecraft’s path will be bent so that it dives into the planet itself. The final descent will occur in mid September, when Cassini enters the atmosphere where it will soon begin to spin and tumble, lose radio contact with Earth, and then ultimately explode due to pressures created by the enormous planet.

All the while it will be taking pioneering measurements, and sending back images predicted to be spectacular.