Seldom does one rock outcrop get so many visitors in a day, especially when that outcrop is located in rugged, frigid terrain abutting the Greenland Ice Sheet and can be reached only by helicopter.

But this has been a specimen of great importance and notoriety since it appeared from beneath the snow pack some eight years ago. That’s when it was first identified by two startled geologists as something very different from what they had seen in four decades of scouring the geologically revelatory region – the gnarled Isua supercrustal belt – for fossil signs of very early life.

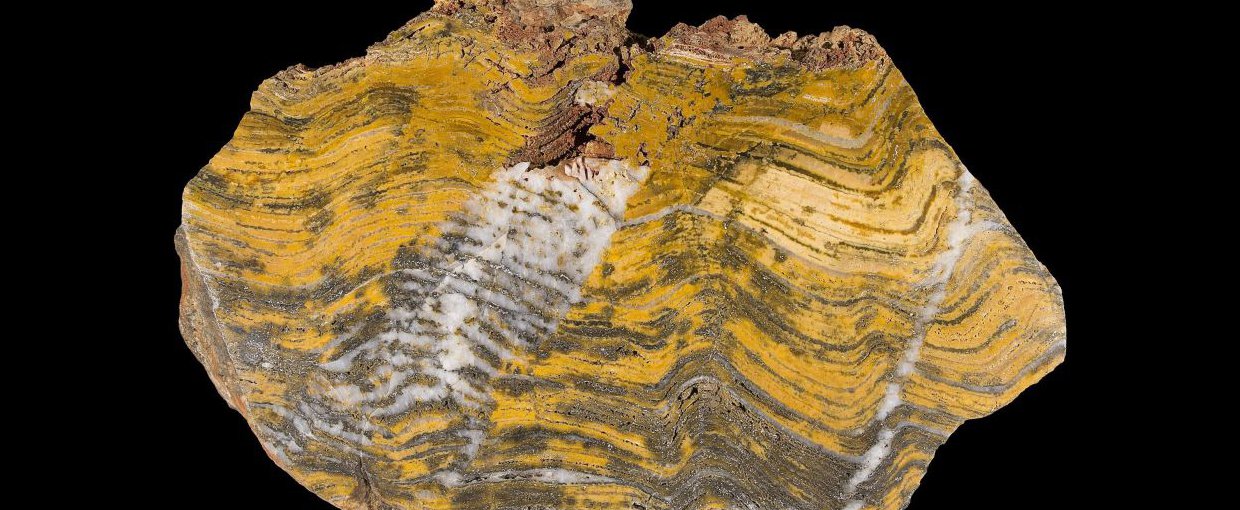

Since that discovery the rock outcrop has been featured in a top journal and later throughout the world as potentially containing the earliest signature of life on Earth – the outlines of half inch to almost two inch-high stromatolite structures between 3.7 and 3.8 billion years old.

If Earth could support the life needed to form a primitive but hardly uncomplicated stromatolites that close to the initial cooling of the planet, then the emergence of life might not be so excruciatingly complex after all. Maybe if the conditions are at all conducive for life on a planet (early Mars comes quickly to mind) then life will probably appear.

Extraordinary claims in science, however, require extraordinary proof, and inevitably other scientists will want to test the claims.

The vigorously debated stromatolites from the Isua greenstone or supercrustal belt, a 1,200-square-mile area of ancient rocks in Greenland. Proponents say the rises, from .4 to 1.6 inches tall, are a signatures of bacteria and sediment mounds called stromatolites. Critics say they are the result of non-biological forces.Image credit: Nature and Nutman et al..

Within two years of that initial ancient stromatolite splash in a Nature paper (led by veteran geologist Allen Nutman of the University of Wollongong in Australia), the same journal published a study that disputed many of the key observations and conclusions of the once-hailed ancient stromatolite discovery. The paper concluded the outcrop had no signs of early life at all.

Debates and disputes are common in geology as the samples get older, and especially in high profile science with important implications. In this case, the implications of what is in the rocks reach into the solar system and the cosmos. And that’s why a dozen scientists were on site to examine the outcrop in late August.

The team that disputed the initial report was led by Abigail Allwood of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, a noted geologist and astrobiologist. She is also principal investigator of a key instrument on the Mars 2020 rover that will be searching for biosignatures — the same kind of signs of past life in dispute at Isua.

It was at her instigation that this most uncommon gathering was planned, bringing together the scientific rivals as well as ten other scientists to meet at the distant outcrop to examine the putative stromatolites together, to study the geological and geochemical context and to later present their cases.

Site A in the Isua supercrustal belt, where one team of scientists argue remains were found of 3.7 billion-year-old life.Image credit: Marc Kaufman.

The gathering was supported by NASA and its Astrobiology Program, which has numerous reasons to be especially interested in the question of the provenance of the Isua stromatolites. Certainly the agency wants to know what they might or might not say about Earth’s earliest life, but also they wanted to know what the site could tell them about the even thornier question of how to identify biosignatures on Mars and beyond.

That, in fact, was an engine driving the expedition. At this point in space science and deep time science, the issue of biosignatures is both central and confounding. They are the pathway to learning if life has existed beyond Earth but, as has become increasingly clear, they are very difficult to find and even harder to interpret.

Allwood described the kind of biosignatures now being pursued as follows: While insects encased in amber can be seen and immediately identified, biosignatures are more like the “footprints and trapped breath of insects. Textual and chemical ghosts.”

Dawn Sumner, one of the geologists present at Isua and someone with long experience looking for microbial influences in old rocks on Earth and on Mars (as a leader of the Curiosity Mars rover team ), put it another way. The dynamic playing out, she said, is “a kind of detective game, but one with very few good clues.” Even when microbes influence rocks, the clues often disappear when those rocks are heated and deformed.

No clear signs of life have been found in rocks as old as Isua’s, which are accepted to be in the range of 3.7 to 3.8 billion years old. Any clues that might indicate life was present have generally been obliterated by the churning of the Earth’s crust, or are more subtle than the ability of today’s science to detect them. Which is too bad, because the very old rocks hold the information needed to understand the origins of life on Earth and early evolution, as well as whether life might exist beyond our planet.

So it was quite an important and dramatic moment when an Air Greenland helicopter landed on a rocky piece of Isua land, and the final group of scientists jumped out and descended to what is known as Site A. ( A previous group of eight had already been in the field for two days.)

The scientists clambered down a rocky slope to the contested site, eager to see and touch and study the ancient and controversial outcrop, and to hear what it might have to tell.

On the other side of the ridge from Site A is the beginning of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Notice the twisted rocks, a feature of the intense past geological activity in the Isua area.Image credit: Marc Kaufman.

The first to present was Nutman, who has been studying the twisted, deformed Isua geology — miles upon miles on foot — for more than four decades. The prized outcrop is quite smooth and unlike most all rocks in the area. And that is what initially fascinated Nutman and his colleague, Clark Friend, when they came across the outcrop, which had before always been covered with snowpack.

Unlike the surrounding outcrops that showed enormous twisting and turning, with evidence of melting and reforming, this one looked like it could have been substantially unchanged since it was formed, Nutman concluded, on the bottom of a shallow sea. And on this outcrop, Nutman and Friend saw four layers of about 20 small mounds and triangles that immediately struck them as being stromatolites.

Stromatolites — which still grow on Earth, most famously at Shark Bay in Western Australia — are formed when layers of sticky microbial biofilm collect sediments to their surfaces. That sediment gradually cuts off nutrients for the biofilm and so a new layer of biofilm grows atop the sediment layer. This can go on for ages, building up a layered structure that can get quite tall. Because they are fossilized structures produced in conjunction with biology that does not get fossilized, stromatolites provide an unmatched window into life on early Earth. But they are also hard to interpret.

In the case of the mounds and triangles at Site A, most of them are pointing down, which is definitely not how a stromatolite would grow. But since everything in the area had been twisted and turned so much, upside down stromatolities hardly seemed like a difficult problem to overcome.

Allen Nutman and Stanley Awaramik of the University of California, Santa Barbara at Site A. Awaramik is a leader in the study of ancient stromatolites, which are very useful in assessing biosignatures of early life because their fossilized structure remains long after their biofilms are gone. Awaramik said that it was not at all certain that the rock preserves evidence that ancient biofilms helped build those structures. You couldn’t rule out the possibility, he said, but he did not consider the likelihood to be high.Image credit: Marc Kaufman.

But what was difficult was to explain how and why this outcrop had not been deformed like everything else around it. After all, the rocks had all been pulled down into the Earth’s crust over the eons and baked at very high temperatures. And Nutman told me that before his discovery, he and his colleagues considered Isua “to be in too bad condition to ever find stromatolites; we used to joke about it.”

As Nutman explained it, the preservation at Site A was a “one in a trillion” event, but one with known geological precedence. It sometimes happens that a piece of the surface gets preserved in the upper fold of crashing subsurface forces, and later returns to the surface without being greatly deformed. Certainly unlikely, he said, but it’s also unlikely that one or two homes always seem to be untouched by tornadoes that sweep through and destroy everything else around them.

Abigail Allwood at Site A, measuring the orientation of lines and planes with a Brunton compass. She was checking to see if the trend and plunge of the lines on top of the rock (which resulted from elongation) were similar to the trend and plunge of the long axes of the structures that had been interpreted as stromatolites. She said that it was.Image credit: Marc Kaufman.

Nutman went on to say that the presence of the mineral dolomite, as well as some rare Earth elements, told of a seawater and sedimentary past. Some isotopic signatures in the area were also important, he has argued for some time, though with substantial pushback. And the area has numerous banded iron formations, a sedimentary signature of the long ago presence of seawater.

These findings and more had been sufficiently persuasive to convince four reviewers at Nature in 2016, including Allwood herself, to recommend the piece be published. She also wrote an accompanying commentary that discussed the major implications of the find, while writing as well that the finding needed considerably more data and proof.

Soon she decided that she needed to visit the site herself. Already well respected for her work in proving (quite convincingly) the biological origins of stromatolites almost 3.5 billion years old in the Pilbara section of western Australia, she has been a hand’s on geologist who needs to collect samples and analyze geological contexts. So she made plans to visit the site in 2017.

By that time she had begun collaborating with Minik Rosing, a Greenlandic-born, Danish geologist who has also spent many long weeks and months in Isua. As it turns out, Rosing, a professor at the University of Copenhagen and chairman of the board of the University of Greenland, had written a letter to Nature vigorously contesting the Nutman paper, but the editors had decided not to publish it.

Allwood and Rosing got connected and planned their own trip to Isua and the site of Nutman’s discovery. Both say that after a short time at the location, they were convinced that the reported stromatolites were not in fact stromatolites.

A fossil stromatolite, with clear laminations, from Strelley Pool in Western Australia. In 2009, Allwood was lead author on a paper that reported the oldest stromatolite convincingly proven to be a product of biology ever found in Strelley. That stromatolite fossil was determined to be 3.45 billion years old.Image credit: Wikipedia.

What struck her right away, Allwood said at the recent Site A visit, was that the stromatolites appeared to be lined up in rows, all on the same plane of the rockface. “It was like they were little children with their toes lined up,” she said. On the sea floor, stromatolites would not present like that.

Allwood, and other scientists at the site, also studied two disquieting aspects of the earlier stromatolite identification: the apparent absence of the lamination lines characteristic of stromatolites and also that some of the features on the outcrop had rather pointed tops, which is not characteristic of stromatolites found in the environment proposed by Nutman.

But it was the seeming absence of laminations that weighed on Dawn Sumner and Stanley Awaramik in particular — both experts in the field. Because stromatolites are formed by layers, it is in their essential nature to present as layered objects.

Nutman argued that some faint lamination lines could be seen and that the age of the samples and infiltration of obscuring minerals could account for the less than robust laminating. The argument, however, met with resistance; the absence of a feature doesn’t prove that it once existed. In addition, the scientists knew that Allwood had done some cutting edge, ultra-high resolution examination of the forms presented as stromatolites and found no evidence of life having been present when they formed.

That instrument is the Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry (PIXL), which can rapidly measure elemental chemistry at sub-millimeter scales and can determine where those chemicals are in relation to each other. PIXL, which will be the subject of a later story, will fly to Mars as part as a key instrument on the 2020 rover. The principal investigator for PIXL is Allwood.

Minik Thorleif Rosing of the University of Copenhagen, a Greenlander by birth who has studied the rocks of Isua for decades.Image credit: Dawn Sumner.

Nutman has a number of significant geological findings to his name and is no stranger to controversy. He says, in fact, that he expects it and showed himself to be willing to go to the field, and have a follow-up workshop, with scientists likely to reject many of his interpretations. He also said that he is in the Isua stromatolite debate for the long haul and that he didn’t expect the question to have a clear resolution for another five to ten years.

Among the most active skeptics is Rosing, a prominent international geologist himself. He and Nutman had actually worked together for a while some decades ago and had each developed a very different theory about the overall shape and nature of the Isua belt.

When the geology team was at the Isua site, Rosing led them across a boulder field to a large outcrop with long-ago lithified bands of brown carbonate minerals. These bands, he said, pointed to something important about the geological context in which the “stromatolite” outcrop lies.

Carbonates can be formed through biology — seashells, for instance, or stromatolites — or through abiotic processes.

While Nutman argued that the dolomite carbonates surrounding the Site A structures were formed from biology, Rosing pointed to the outcrops with carbonate bands as a sure sign that the mineral was actually formed without biology and was common throughout the area.

In addition, Rosing was persuaded that he knew where the carbonates came from. A short way up the rocky valley Rosing had found a large deposit of the clay mineral hydrated magnesium silicate — better known as talc. The mineral, he explained, releases its carbon dioxide under the heat and stress of tectonic burial (at Isua, at a depth of 15 miles and at temperatures of 500 degrees F) and that can form the carbonates found on nearby ridges and at Site A itself. The bands Rosing showed would be flowing carbonates in the deep-Earth oven.

“The carbonates are everywhere and I wanted to see if I could find a talc origin,” he said. “So I walked up the valley and there it was; a large deposit. It was one of those satisfying times when predictions are confirmed. We don’t need a biological source to explain the carbonates and the dolomite (a form of carbonate) they found in Site A and interpreted as having come from biology.”

The key to Isua, he said, is identifying the geological and geochemical connections between its varied parts, and then to come up with the most straight-forward explanation of why things are as they are.

Isua outcrop with rock layers pushed and pulled in ways that produce brown carbonate structures that look similar to the hypothesized stromatolites.Image credit: Mark Van Zuilen.

One of the geologists on several long explores was Mark Van Zuilen of the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris. In his wanders, he looked for examples of “folding” in rock faces, a sign that the material had been under great geological stress and had buckled.

He and I were on two outcrops where we saw that phenomenon and gradually it became apparent that little bumps and even dome-like structures were pretty common in the outcrops. The face of the rocks were much more weathered than that of Site A, but the rock there had been protected by the snowpack for untold centuries and so might be expected to be smoother. Also, Nutman et al had argued that the geological compression and folding at Site A was on a substantially wider scale than anything like the samples found by Van Zuilen.

The inevitable question was whether or not the same deformation forces that formed all the bumps found at many other Isua outcrops might have also formed the “stromatolites” structures. The possibility was great enough that other members of the team wanted to cross some more boulder fields and take a look.

Later, Nutman colleague Clark Friend said that the “bumps” were geological structures called mullions, which occur when rocks are strongly deformed. He called them entirely different from the hypothesized stromatolites, but not all the geologists seemed convinced.

Joel Hurowitz, a geochemist and planetary scientist at of Stoney Brook University, was one of the scientists who found the bumps on the more distant outcrop to be intriguing. He later searched for similar features closer to Site A, found them, and later presented them to the full entourage. He agreed that what he and Van Zuilen had found probably are mullions but added “why shouldn’t we also consider the Site A structures to be mullions of some kind, especially given how common they appear to be in the area?”

By the end of the gathering, there was no real consensus in terms of the stromatolites in that Nutman and Friend held fast to their interpretation and so did Allwood. But the other scientists did reach a general consensus that the evidence presented did not clear the high bar that comes with the claim of having found the oldest sign of life on Earth. Some, however, left the door open for new evidence that could conceivably change minds.

That there could be such disagreements about outcrops and rocks that are sizeable, touchable and testable illustrates precisely why an outing like the one of Isua is significant, and the logic gets back to the question of biosignatures. They are, to say the least, a challenge.

Allwood and James Bell of Arizona State University, principal investigator of the Mastcam-Z camera system on the Mars 2020 rover. The two were at Site A discussing whether they would recommend stopping to do a full study of the rock if they saw it on Mars. Bell said “yes,” Allwood wasn’t sure and said the geological context would determine her answer.Image credit: Marc Kaufman.

So it was no coincidence that four members of the Isua geology expedition were principal investigators for instruments going to Mars in 2020.

They are Allwood and the PIXL instrument; James Bell, who will lead the Mastcam-Z team and its camera system with panoramic, zooming and stereoscopic imaging capabilities; Luther Beegle of SHERLOC , which uses spectrometers, a laser and a camera to search for organics and minerals that have been altered by watery environments; and Svein-Erik Hamran, in charge of the RIMFAX instrument, which looks for geologic features under the surface with ground-penetrating radar. (That instrument will be the first developed and built in Norway to operate on Mars.)

The first three instruments are key to identifying sites that have attributes that could preserve biosignatures and deserve a closer look, which SHERLOC and especially PIXL will give. They will be looking for those most subtle anomalies that, as Allwood put it, represent “textual and chemical ghosts.”

And so why would Isua be especially important to these scientists? As Bell put it, the Mars instruments will be looking for signs of ancient life going back to the same period — some 3.5 to 4 billion years ago — that they were studying in Isua. That 3.5 to 4 billion years ago period was Mars was much wetter and warmer, and when life just might have started. And unlike on Earth, the geology would have stayed pretty much the same since there since tectonics on Mars appears to be much less vigorous than tectonics on our planet.

“When we land on Mars, we’ll be on rocks about the same age as here at Isua,” Bell said. “Rocks that have very different histories, but are from the same period in the history of the solar system…That’s something big to take in.”

And no doubt some of those rocks will have features that put them in the potential biosignature category. As the Isua rocks demonstrate, that’s an very exciting, compelling arena for scientists.

But it’s also a most uncomfortable place because there are so many reasons why a potential biosignature needs to be taken seriously, and so many reasons why it should not. That’s what happens when your goal is, at its most challenging, to “find the trapped breath of insects.”

A pioneering three-dimensional, virtual reality look at a Greenland outcrop earlier described as containing 3.7-billion- year-old stromatolite fossils, which would be the oldest remnant of life on Earth. The video capture, including the drone-assisted overview of the site, is part of a much larger virtual reality effort to document the setting undertaken late in August. As the video focuses in on the scientifically controversial outcrop, cuts are visible in the smooth surfaces that were made by two teams studying the rocks in great detail to determine whether the reported stromatolite fossils are actually present. (Parker Abercrombie, NASA/JPL and Ian Burch, Queensland University of Technology.)

The Many Worlds Blog chronicles the search for evidence of life beyond Earth written by author/journalist Marc Kaufman. The “Many Worlds” column is supported by the Lunar Planetary Institute/USRA and informed by NASA’s NExSS initiative, a research coordination network supported by the NASA Astrobiology Program. Any opinions expressed are the author’s alone.