A study released today is the first to refine where environments suitable for life, more complex than microorganisms, might be able to exist beyond our own solar system.

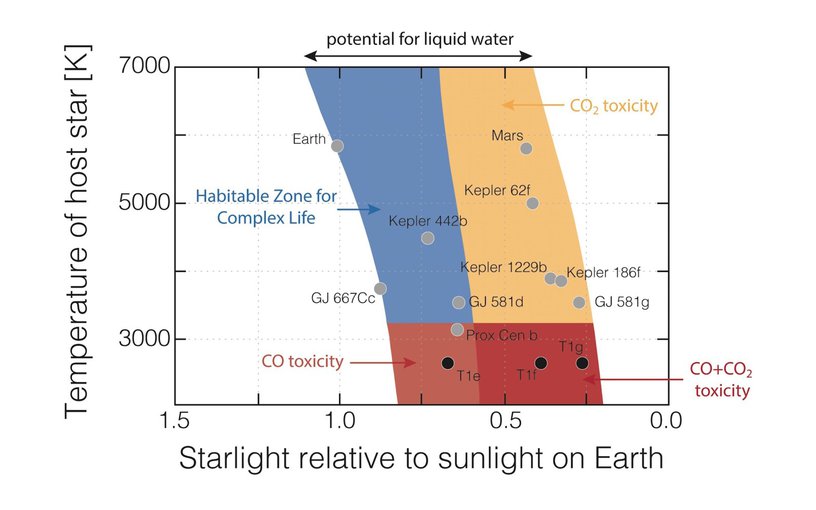

Research funded by the NASA Astrobiology Program through the NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI) concludes that increased levels of toxic gases significantly narrow the habitable zone for complex life. Scientists define the traditional habitable zone as the distance from a star where there is enough heat for liquid water to persist on a planet’s surface.

Life as we know it requires liquid water to survive, and planets within the habitable zone of a star are thought to be the best candidates for supporting microbial life. However, microorganisms are able to thrive in conditions that are not suitable for more complex life. The new study provides the first estimation of a narrow habitable zone for complex life, where planets might be able to support animal-like organisms.

Using models for atmospheric climate and photochemistry, scientists compared predicted carbon dioxide (CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) levels to previously determined toxicity limits that quantitatively designate the safe zone for macroscopic life on exoplanets.

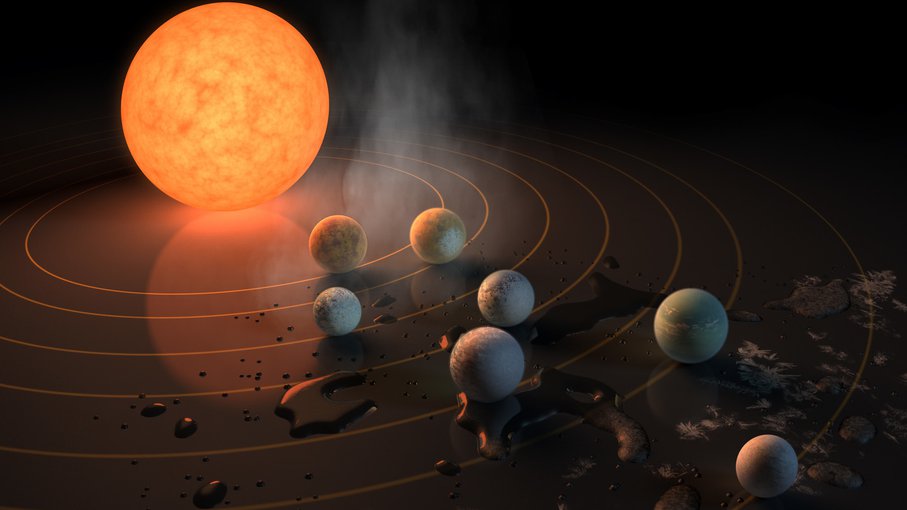

Three planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1 fall within that star’s habitable zone.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

“This is the first time the physiological limits of life on Earth have been considered to predict the distribution of complex life elsewhere in the universe,” said Timothy Lyons, study co-author, distinguished professor of biogeochemistry at the University of California, Riverside’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and director of the NAI’s Alternative Earths Astrobiology Center, which sponsored the project.

The study has important implications in the the search for biological complexity in the universe, and in determining the best places to look for signs of intelligent life or potential evidence of technology.

“This study will shape the development of new technologies, missions, and more powerful telescopes that we will use to search the sky for signatures of life beyond the Solar System,” said Mary Voytek, NASA Astrobiology Program director.

According to Voytek, studies like this are important in helping us decide where to focus our search, and the instruments we will need. Ultimately this increases the likelihood of finding evidence that Earth isn’t the only planet in the vastness of space where life exists.

This newly-revealed science is also a critical part of NASA’s work to understand the universe, advance human exploration, and inspire the next generation. As NASA’s Artemis program moves forward with human exploration of the Moon, the search for life on other worlds remains a top priority for the agency.

The Habitable Zone for Complex Life. Schwieterman et al. (2019)Image credit: Christopher Reinhard at Georgia Institute if Technology.

Lead author of the study, Edward Schwieterman, is supported through the NASA Astrobiology Program as a NASA Postdoctoral Program fellow with the Alternative Earths Astrobiology Center at UCR. Timothy Lyons, co-author of the study and Schwieterman’s advisor at UCR, is a project co-lead for the new NASA Astrobiology RCN Prebiotic Chemistry and Early Earth Environments Consortium (PCE3). Additional co-authors of the study include Christopher Reinhard, assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Stephanie Olson of the University of Chicago, and Chester E. Harman of Columbia University.

The paper, “A Limited Habitable Zone for Complex Life” is published in The Astrophysical Journal and can be found at: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ab1d52

Click here to read the press release from UC Riverside.

Dwayne Brown / Alana Johnson

Headquarters, Washington DC

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1501

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov