Nov. 1, 2016

Research Highlight

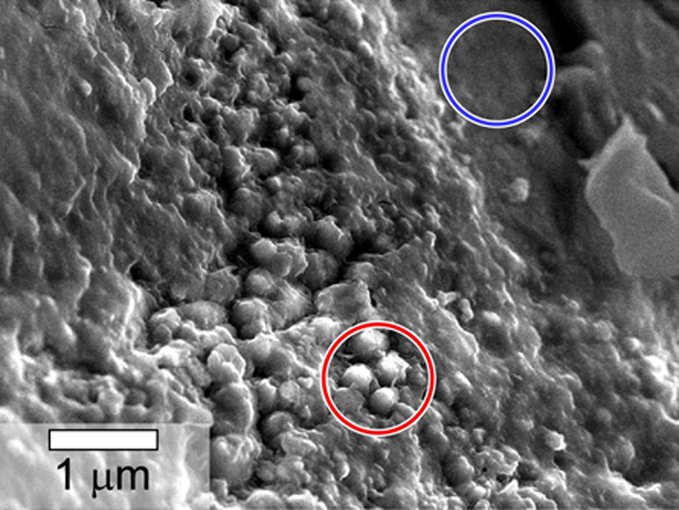

Microscope Could Seek Biological Samples on Red Planet

This is a scanning electron microscope image showing spheroidal features (circled) on Yamato 000593 — a meteorite found on Earth that originated on Mars. The features were found in a layer of iddingsite, which is a mineral created in water. Investigators hope to bring high-definition scanning electron microscopes to the Martian surface. Credit: NASA

One of the ultimate goals of Mars exploration is to bring samples from the surface to Earth, especially those that could be examined for evidence of life on the Red Planet.

Such an undertaking would be expensive and the samples risk contamination during their journey to Earth. So, one option is to analyze the samples in their natural habitat on Mars before bringing them to the Earth for further study. The Mars Science Lab and other Mars rovers are already studying samples on Mars in-situ with an array of instruments that image and assess the chemical make-up of various Mars samples. However, there are only a few techniques that can unambiguously determine if life is present.

On Earth, one instrument that scientists use to examine living and other biological materials is an atmospheric or environmental scanning electron microscope (ASEM or ESEM). ESEMs are capable of imaging with a resolution of better than 10 nanometers, or roughly a 1000th the width of a human hair, and are also capable of determining the composition of the same sample. Commercial ESEMs are typically very large and power-hungry. However, one team has undertaken the challenge of miniaturizing an ESEM to make it suitable for in-situ operation on Mars.

The Miniaturized Variable Pressure Scanning Electron Microscope (MVP-SEM) is a NASA-funded project based on concepts that could be used on the International Space Station and on the Moon. The next goal is to create an ESEM-type instrument that will allow scientists to study Martian geology and to look for microbes on the surface of Mars, on some yet-to-be determined mission.

“By putting this capability on a rover or lander, not only can we better select the samples for return, but primarily we will be able to carry out high-quality imaging and analysis on Mars without the risk of contamination from a sample brought to the Earth for study,” said Jessica Gaskin, the principal investigator of the project.

The project was presented at the Lunar Planetary Science Conference earlier in 2016. It is funded under the NASA Planetary Instrument Concepts for the Advancement of Solar System Observations (PICASSO) program.

A NASA team practices techniques that could be used for astronauts on Mars. Sample return missions will help determine what sites on Mars can be safely visited. Credit: NASA

Instrument development

Atmospheric or variable pressure scanning electron microscopes are used in laboratories for research in many disciplines, ranging from medicine to geology. The particular instrument NASA funded will study geological materials in such a way that will allow the samples to remain intact. Because the process does not destroy the sample, it can then be analyzed by other instruments so that a more complete picture can be formed of the sample’s origin and possible evolution.

The instrument will allow for high-resolution imaging (of better than 50 nanometers) and for Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS), or chemical mapping to determine chemical composition. These SEMs have a large field depth with the ability to look at a large swath of material and do not require the samples to be prepared ahead of examination time, which simplifies operations for a rover working far from humans.

“The key to this specific technology,” Gaskin said, “is that it will use the Mars atmosphere as our imaging gas. This will allow us to observe raw (conductive and non-conductive) uncoated samples in their natural environment.”

One criticism of astrobiology is the tendency to look for familiar carbon-based life that would thrive in the presence of water. A strategy to broaden the search for life is to look for some sort of disequilibrium within a surrounding that can’t easily be explained by physics or chemistry. For example, if a large amount of silicon was seen in a particular environment, a possible explanation could be the presence of life. The spectrometer would be capable of detecting disequilibriums in the environment.

“This instrument would also provide high enough resolution imaging to identify bio-signatures,” said Jennifer Edmunson, the project scientist for MVP-SEM.

The Curiosity rover working in Gale Crater on Mars. One major goal of NASA’s Mars program is to look for habitable environments in the past and present. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

An example would be finding proteins from microbes, such as Pyrobaculum aerophilum, a bacterium that thrives in boiling water. “One goal of our instrument development is to be able to differentiate compounds like calcium oxalate (a potential bio-signature) from calcium carbonate,” Edmunson added.

Microbes that live in extreme environments on Earth are sometimes used as models for theoretical microbes that could live in the cold, salty waters of Mars. Also, in the event that any life form may be exposed on some sample surface, such as dry spore-like life form, our instrument should be able to capture an image for subsequent interpretation and study.

The MVP-SEM will use a secondary electron detector to help scientists learn about microscopic surface features, as well as a backscatter electron detector to provide texture and composition information for a sample. An EDS detector will also be used to study the chemical composition. Currently, the team is defining the optimum for operation in Mars’ carbon-dioxide rich atmosphere, after which a prototype will be developed and tested in a Mars environmental chamber at JPL. Key participants in this effort other than MSFC include JPL, Creare, Applied Physics Technologies, Case Western Reserve University and advisor Dr. G. Danilatos (early pioneer of the atmospheric or environmental SEM).

When the PICASSO work is finished, the team plans to continue developing the instrument through a NASA Maturation of Instruments for Solar System Exploration (MatISSE) grant, which is a part of the agency’s Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Science program. PICASSO supports the development of spacecraft-based instrument systems that show promise for use in future planetary missions. The goal is to conduct planetary and astrobiology science instrument feasibility studies, concept formation, proof of concept instruments, and advanced component technology development (technology readiness levels (TRL) 1 – 3) to the point where they may be proposed in response to the Maturation of Instruments for Solar System Exploration (MatISSE) Program.