March 16, 2016

Feature Story

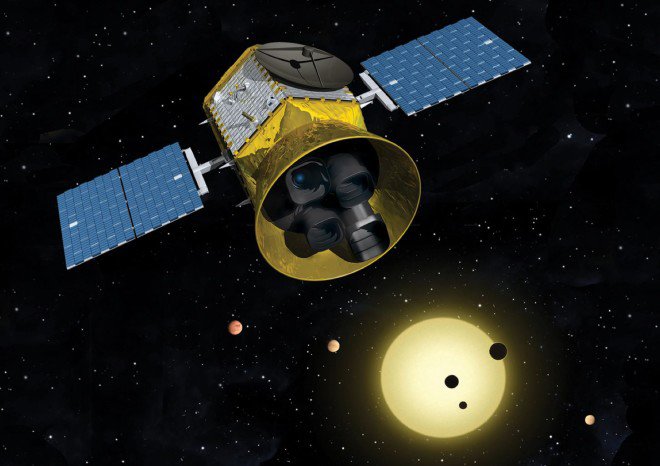

Hunting for Exoplanets Via TESS

The TESS satellite, which will launch in 2017, will use four cameras to search for exoplanets around bright nearby stars. MIT initially proposed the mission, and it was approved in 2013. Image credit: MIT

Seven years ago this month the Kepler spacecraft launched into space – the first NASA mission dedicated to searching for planets around distant stars. The goal was to conduct a census of these exoplanets, to learn whether planets are common or rare. And in particular, to understand whether planets like Earth are common or rare.

With the discovery and confirmation of over 1,000 exoplanets (and thousands more exoplanet candidates that have not yet been confirmed), Kepler has taught us that planets are indeed common, and scientists have been able to make new inferences about how planetary systems form and evolve. But the planets found by Kepler are almost exclusively around distant, faint stars, and the observations needed to further study and characterize these planets are challenging. Enter TESS.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a NASA Explorer mission designed to search for new exoplanets around bright, nearby stars. The method that TESS will use is identical to that used by Kepler – it looks for planets that transit in front of their host star. Imagine that you’re looking at a star, and that star has planets around it.

If the orbit of the planet is aligned correctly, then once per “year” of the planet (i.e. once per orbit), the planet will pass in front of the star. As the planet moves in front of the star, it blocks a small fraction of the light, so the star appears to get slightly fainter. As the planet moves out of transit, the star returns to normal brightness. We can see an example of this in our own solar system on May 9, 2016, as Mercury passes in front of the Sun.