What observations, or groups of observations, would tell exoplanet scientists that life might be present on a particular distant planet?

The most often discussed biosignature is oxygen, the product of life on Earth. But while oxygen remains central to the search for biosignatures afar, there are some serious problems with relying on that molecule.

It can, for one, be produced without biology, although on Earth biology is the major source. Conditions on other planets, however, might be different, producing lots of oxygen without life.

And then there’s the troubling reality that for most of the time there has been life on Earth, there would not have been enough oxygen produced to register as a biosignature. So oxygen brings with it the danger of both a false positive and a false negative.

Wading through the long list of potential other biosignatures is rather like walking along a very wet path and having your boots regularly pulled off as they get captured by the mud. Many possibilities can be put forward, but all seem to contain absolutely confounding problems.

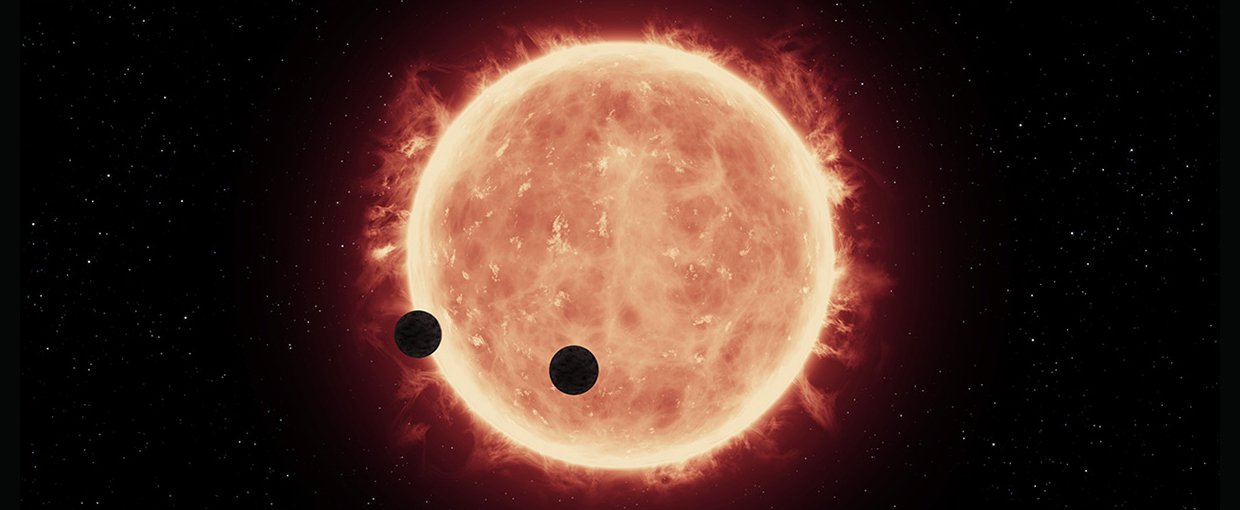

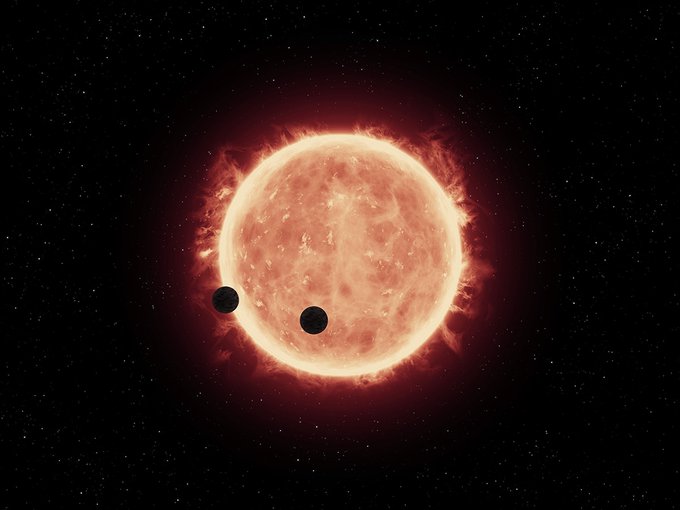

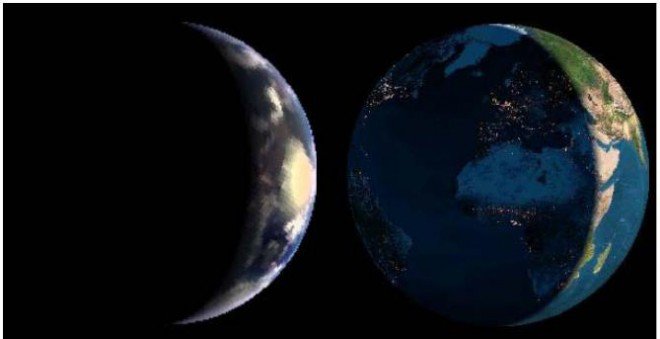

Artist’s illustration of two Earth-sized planets, TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c, passing in front of their parent red dwarf star, which is smaller and cooler than our sun. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope looked for signs of atmospheres around these planets.Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI/J. de Wit, MIT.

With this reality in mind, a group of several dozen very interdisciplinary scientists came together more than a year ago in an effort to catalogue the many possible biosignatures that have been put forward and then to describe the pros and the cons of each.

“We believe this kind of effort is essential and needs to be done now,” said Edward Schwieterman, an astronomy and astrobiology researcher at the University of California, Riverside (UCR).

“Not because we have the technology now to identify these possible biosignatures light years away, but because the space and ground-based telescopes of the future need to be designed so they can identify them. “

“It’s part of what may turn out to be a very long road to learning whether or not we are alone in the universe”.

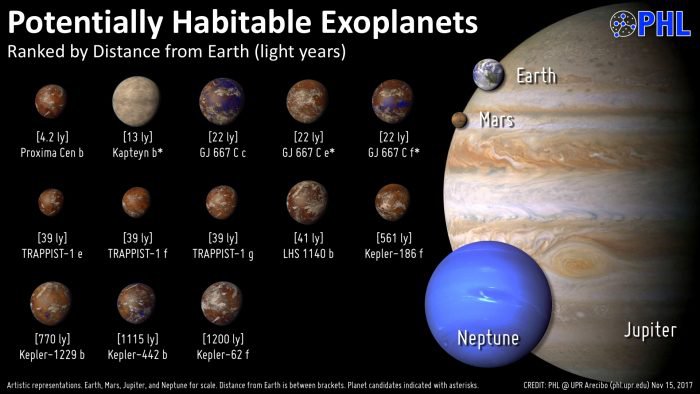

Some exoplanets detected with the greatest potential to support liquid surface water, based on size and orbit. All are larger than Earth and composition/habitability remains unclear. Mars, Jupiter, Neptune and Earth shown for scale.Image credit: Planetary Habitability Laboratory, managed by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo.

The known and inferred population of exoplanets — even small rocky exoplanets — is now so vast that it’s tempting to assume that some support life and that some day we’ll find it. After all, those billions of planets are composed of same basic chemical elements as Earth and are subject to the same laws of physics.

That assumption of life widespread in the galaxies may well turn out to be on target. But assuming this result, and proving or calculating a high probability of finding extraterrestrial life, are light years apart.

The timing of this major community effort is hardly accidental. There is a National Academy of Sciences effort underway to review progress in the science of reading possible biosignatures from distant worlds, something that I wrote about recently.

Edward Schwieterman, spent six years at the University of Washington’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory. He now works with the NASA Astrobiology Institute Alternative Earths team UCR.Image credit: UCR.

The results from the NAS effort will in term flow into the official NAS decadal study that will follow and will recommend to Congress priorities for the next ten or twenty years. In addition, two NASA-ordered science and technology definition teams are currently working on architectures for two potential major NASA missions for the 2030s — HabEx (the Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission) and Luvoir (the Large Ultraviolet/Optical/Infrared Surveyor.)

The two mission proposals, which are competing with several others, would provide the best opportunity by far to determine whether life exists on other distant planets.

With these formal planning and prioritizing efforts as a backdrop, NASA’s Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) called for a biosignatures workshop in the fall of 2016 and brought together scientists from many disciplines to wrestle with the subject. The effort led to the white paper submitted to NAS and will result in and will result in the publication of series of five detailed papers in the journal Astrobiology this spring.” The overview paper with Schwieterman as first author, which has already been made available to the community for peer review, is expected to lead off the package.

So what did they find? First off, that Earth has to be their guide.

“Life on Earth, through its gaseous products and reflectance and scattering properties, has left its fingerprint on the spectrum of our planet,” the paper reads. “Aided by the universality of the laws of physics and chemistry, we turn to Earth’s biosphere, both in the present and through geologic time, for analog signatures that will aid in the search for life elsewhere.

Considering the insights gained from modern and ancient Earth, and the broader array of hypothetical exoplanet possibilities, we have compiled a state-of-the-art overview of our current understanding of potential exoplanet biosignatures including gaseous, surface, and temporal biosignatures.”

In other words, potential biosignatures in the atmosphere, on the ground, and that become apparent over time. We’ll start with the temporal:

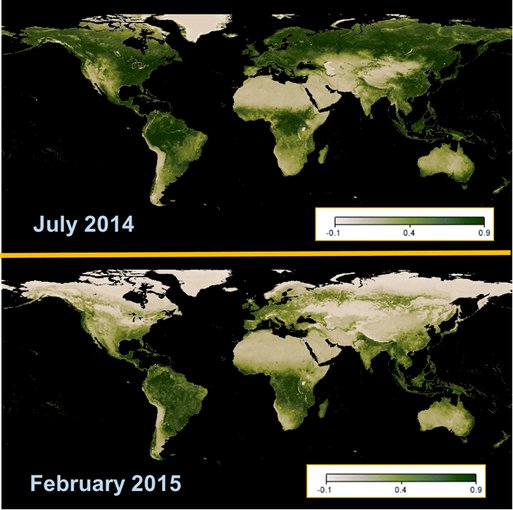

These vegetation maps were generated from MODIS/Terra measurements of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Significant seasonal variations in the NDVI are apparent between northern hemisphere summer and winter.Image credit: Reto Stockli, NASA Earth Observatory Group, using data from the MODIS Land Science Team.

Vegetation is probably clearest example of how change-over-time can be a biosignature. As these maps show and we all know, different parts of the Earth have different seasonal colorations. Detecting exoplanetary change of this sort would be a potentially strong signal, though it could also have some non-biological explanations.

If there is any kind of atmospheric chemical corroboration, then the time signal would be a strong one. That corroboration could come in seasonal modulations of biologically important gases such as CO2 or O2. Changes in cloud cover and the periodic presence of volcanic gases can also be useful markers over time.

Plant pigments themselves which have been proposed as a surface biosignature. Observed in the near infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, the pigment chlorophyll — the central player in the process of photosynthesis — shows a sharp increase in reflectance at a particular wavelength. This abrupt change is called the “red edge,” and is a measurement known to exist only which chlorophyll engaged in photosynthesis.

So the “red edge,” or parallel dropoffs in reflectance of other pigments on other planets, is another possible biosignature in the mix.

And then there is “glint,” reflections from exoplanets that come from light hitting water.

True-color image from a model (left) compared to a view of Earth from the Earth and Moon Viewer (http://www.fourmilab.ch/cgi-bin/Earth/). A glint spot in the Indian Ocean can be clearly seen in the model image.Image credit: fourmilab.

Since biosignature science essentially requires the presence of H2O on a planet, the clear detection of an ocean is part of the process of assembling signatures of potential life. Just as detecting oxygen in the atmosphere is important, so too is detecting unmistakable surface water.

But for reasons of both science and detectability, the chemical make-up exoplanet atmospheres is where much biosignature work is being done. The compounds of interest include (but are not limited to) ozone, methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur gases, methyl chloride and less specific atmospheric hazes. All are, or have been, associated with life on Earth, and potentially on other planets and moons as well.

The Schwieterman et al review looks at all these compounds and reports on the findings of researchers who have studied them as possible biosignatures. As a sign of how broadly they cast their net, the citations alone of published biosignature papers number more than 300.

(Sara Seager and William Bains of MIT, both specialists in exoplanet atmospheres, have been compiling a separate and much broader list of potential biosignatures, even many produced in very small quantities on Earth. Bains is a co-author on one of the five biosignature papers for the journal Astrobiology.)

All this work, Schwieterman said, will pay off significantly over time.

“If our goal is to constrain the search for life in our solar neighborhood, we need to know as much as we possibly can so the observatories have the necessary capabilities. We could possibly save hundreds of millions or billions of dollars by constraining the possibilities.”

“The strength of this compilation is the full body of knowledge, putting together what we know in a broad and fast-developing field,” Schwieterman said. ”

He said that there’s such a broad range of possible biosignatures, and so many conditions where some might be more or less probable, that’s it’s essential to categorize and prioritize the information that has been collected (and will be collected in the future.)

“We have a lot of observations recorded here, but they will all have their ambiguities,” he said. “Our goal as scientists will be to take what we know and work to reduce those ambiguities. It’s an enormous task.”