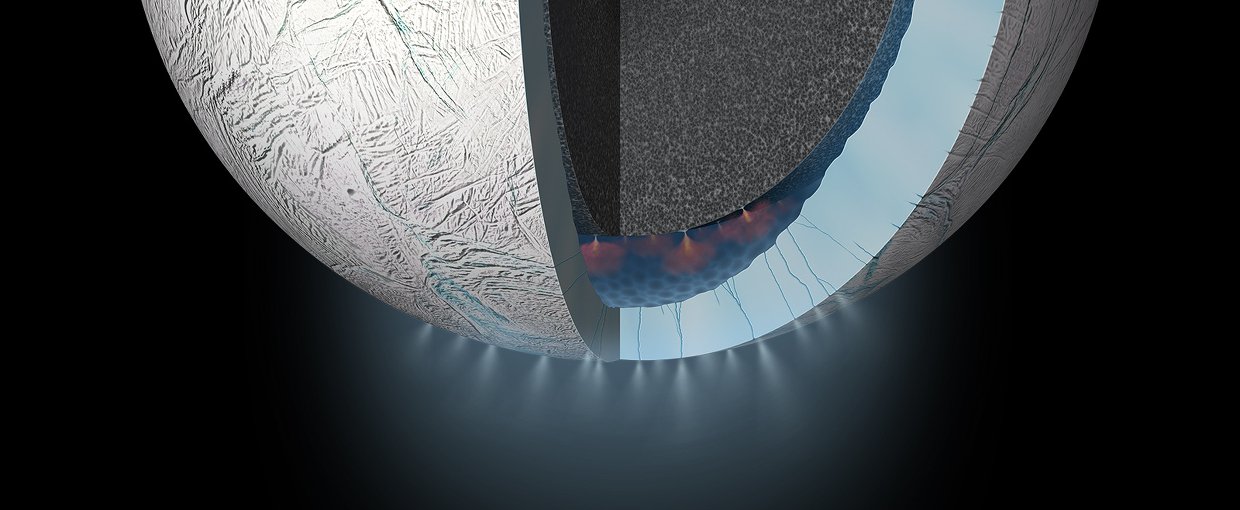

Saturn’s moon Enceladus appears to have a global sub-surface water ocean that, based on all observations made thus far, could be habitable to Earth-like life. One such observation is of co-occurring H2 and CO2 in the plumes of ice and gas that vent to space from the south polar region, and are thought to originate in the underlying ocean. On Earth, microorganisms called methanogens can use H2 and CO2 as a source of energy, combining them in a metabolism that generates methane. So their combined presence on Enceladus represents chemical energy that could be used by life in that world’s ocean.

But could the presence of these gases mean that nobody’s home on Enceladus? If life was present in the ocean and using these compounds for energy, would we see them being vented to space at all? Why would there be food left on the table if there’s anything there to eat it?

Dr. Tori Hoehler, an astrobiologist from NASA Ames Research Center, addresses these questions in a new paper published last month in Nature Astronomy.

The paper identifies three possibilities to explain how H2 and CO2 could be abundant even if life is present on Enceladus: (1) Life is present but does not consume H2/CO2. (2) A population of organisms is growing but has not yet reached its maximum potential for H2/CO2 consumption. (3) Life consumes H2/CO2 and the observed unconsumed energy reflects a system at steady state, with a fully established capacity for biological consumption. That neither of the first two scenarios can be ruled out should suffice to indicate that the observed gases are compatible with life on Enceladus, but the paper examines the third case in detail, as that is the one with greatest potential for H2 and CO2 to be diminished if Enceladus is inhabited.

Hoehler considered a number of environments on Earth that are home to methanogens and showed that the amount of H2 and CO2 – the amount of seemingly ‘unconsumed’ energy – can vary widely depending on rates of turnover of the methanogen population and on the physiological properties of the organisms themselves. None of these factors are presently known for the distant, ice-covered ocean of Enceladus, so we can’t see ‘energy left on the table’ is a sign that life is not present.

“In this light”, Hoehler concludes, “Enceladus remains a no less compelling target in the search for evidence of life beyond Earth.”

The research was supported through elements of the NASA Astrobiology Program.