Written byMichael Toillion

Two years ago, before the world turned upside down, I had the pleasure of accompanying a team of astrobiologists on an incredible journey into the wilderness of Greenland. Led by Dr. Abigail Allwood from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the expedition set out to investigate a claim of biosignatures, in the form of stromatolites, in an outcrop of rocks dating back to 3.7 billion years old. If the claim was true, it would change our understanding of how early life was formed on Earth, in addition to our understanding of life on other worlds, like Mars.

The expedition began in Nuuk, Greenland, where a team of scientists and engineers from all over the world gathered to prepare for the journey ahead. Two teams would take turns traveling by helicopter into the Isua Greenstone Belt, camping in the cold, harsh conditions of Greenland’s wilderness for 3 days and 2 nights. I arrived with my usual filming gear, plus a single person tent, zero-degree sleeping bag, and a nervous excitement for the trip.

Nuuk, Greenland, where the journey began.

Image Credit: Mike Toillion

After a day of meeting the team and finalizing the details of the expedition, we headed to the Nuuk airport, and made our way across the tarmac to the helipad. This was not only my first time to Greenland, but my first time on a helicopter. The trip was breathtaking.

View from the helicopter.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

The team and I flew over bright, turquoise-colored water, rippling from floating ice. We passed glaciers, waterfalls, and rocky islands as I struggled to document everything through a smudged window of the helicopter. The landscape looked truly pristine, as if no human had ever ventured there. After about 45 minutes of air travel, our pilot navigated us down to a rocky ridge overlooking the field site and base camp, our home for the next 3 days.

The team lands, unloads, and heads to the field site.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

I’ll never forget the feeling of standing on that ridge amongst a pile of gear watching the helicopter fade into the distance, realizing that we were truly on our own. Luckily, I was with a team with an incredible amount of field experience. “You’ll be fine. This is nothing,” Dr. Dawn Sumner, professor of earth and planetary sciences from the University of California, Davis, would tell me. Dawn had been on countless field trips to extreme environments and even has a field trip survival blog about tips for taking care of yourself while working in the field.

Dr. Dawn Sumner, professor of earth and planetary sciences, University of California, Davis.

Image Credit: Mike Toillion

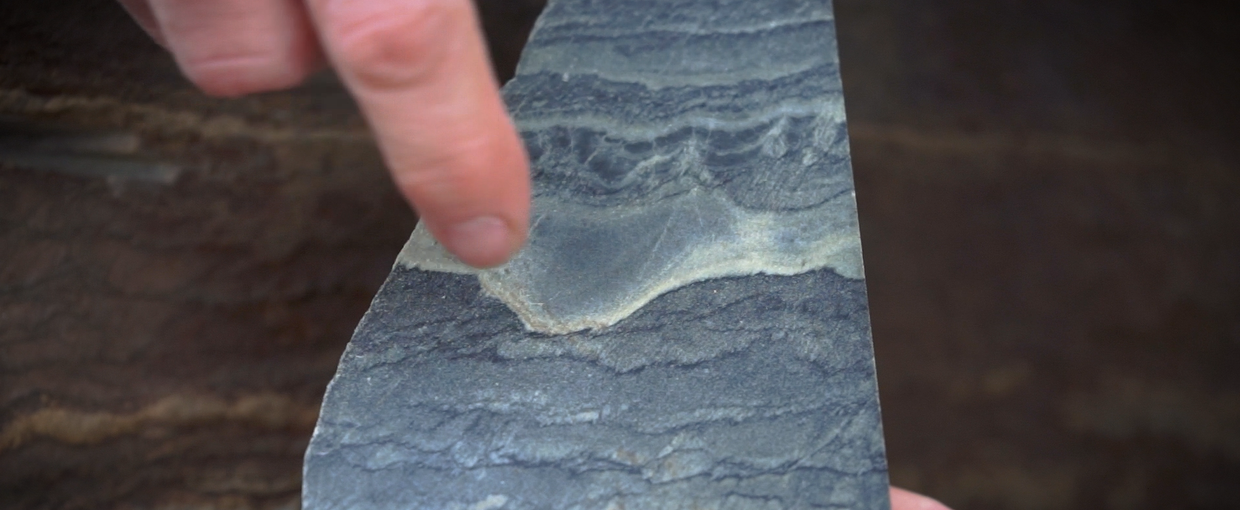

The team hit the ground running, immediately heading to the field site to take a look at the outcrop. Dr. Allwood showed us the site where two samples had been taken from the outcrop, revealing deep cuts in an ancient rock. To prove that a geological structure is a biosignature, scientists need to prove that the structure or chemical contents of a rock could only have been possible through a biological process. Dr. Allwood is an expert in such endeavors, specifically from identifying stromatolites in the Australian outback, the current oldest signs of life known on Earth.

A polished sample taken from the outcrop showing the punitive stromatolite-like structure.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

Claims like these require much scientific rigor, because their implications are extremely important to our understanding of how life formed on Earth, and therefore, how life may have formed on other planets. The current oldest signs of life are about 3.5 billion years old. Since the Earth is 4.5 billion years old, that means the window for life to take hold on a planet (as we currently know) is about 1 billion years. If the claim of biosignatures at this site in Greenland is true, it would shorten that window by over 200 million years! This means that other planets could also begin to form life in a shorter period, extending the list of possible candidates for habitable worlds to search for life.

Dr. Abigail Allwood, Astrobiologist, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Image credit: Mike Toillion

Another goal of the expedition was to further develop Project OnSight, a virtual reality tool developed at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory to assist the NASA Mars mission teams in exploring the surface of Mars. Engineers Parker Abercrombie and Ian Burch used LIDAR and photogrammetry technology to create a 3D model of the entire outcrop and its surrounding area, enabling scientists to explore the region from the comfort of their own labs and offices. While the tool is primarily used to assist Mars rover missions, the Project OnSight team thinks that their tools can be useful for any terrestrial geological survey to help make remote field sites, like the Isua Greenstone Belt, more accessible for all.

Parker Abercrombie, Software Engineer, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, initiates a LIDAR scan.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

After a long day of scientific measurements, sampling, and documenting, the team and I collect our gear and head to the campsite, a wooden hut by a picturesque alpine lake with an incredible view. As the sun began to set, the team and I unpacked our tents and setup camp, taking precautions to tie them down with heavy rocks to withstand the incredibly strong winds expected throughout our stay.

The campsite, our home for the next 3 days.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

Not knowing what to expect, I had brought MRE’s to eat during the trip. Little did I know, our host for this expedition, Dr. Minik Rosing, professor of geology at the University of Copenhagen, knew how to travel in style. As I entered the hut, I was greeted by a candlelit table and the smell of freshly cooked pasta in a bolognese sauce. I meekly offered my pathetic supply of MRE’s and after politely declining, Dr. Rosing offered an appetizer of smoked local fish and an 18 year old bottle of scotch (which we later served over chunks of ice from the nearby glacier). While the cold and wind raged outside, the hut was an incredible scene of warmth and comradery. Needless to say, the MRE’s returned to my pack and were never spoken of again.

Candlelit dinner in the hut.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

That night was the windiest experience of my life. Like a true amatuer, I had setup my single person tent perpendicular to the direction of the wind. The walls of my nylon coffin were pummeled by the air and pressed against my body for the entire night, as I tried to drown out the deafening sound with a podcast. Ian Burch had a much worse time. Ian’s tent completely came loose and he found himself outside in the middle of the night holding onto one of the remaining tethers flying his tent like a kite. “At least I got to see the aurora,” he recounted to us in the morning.

After another two days at the field site, interviewing the team about their findings and learning more about the fascinating geology of the area, the helicopter returned and took us all back to Nuuk. A workshop was held at the University of Nuuk, where the findings were shared and debated with members of the scientific community. I really enjoyed watching the scientific process take place, from hypothesis, to investigation, to debate, and finally, consensus. Before the flight home, Dawn convinced Parker and I to take a quick sea kayaking trip before saying goodbye to the beautiful country of Greenland.

The main expedition team. From left: Dr. Mike Zawaski, Parker Abercrombie, Ian Burch, Dr. Dawn Sumner, Dr. Minik Rosing, Marc Kaufman, Dr. Mark van Zuilen, Mike Toillion, and Dr. Joel Hurowitz.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

Traveling to Greenland and being a part of this expedition was one of the greatest experiences of my life, and I feel incredibly grateful to Dr. Allwood and NASA for the opportunity. You can watch the full episode of Astrobiology in the Field: Greenland on the NASA Astrobiology YouTube channel. I hope you enjoy it!

First selfie after a 3-day expedition. Mike Toillion, creator of the Astrobiology in the Field series.

Image credit: Mike Toillion

Is your NASA-funded team conducting fieldwork in 2022?

Would you like to participate in the next episode? NASA Astrobiology is looking for the next team to highlight in our Astrobiology in the Field series! If your team is selected, I will accompany your team to your field site and produce a short documentary for the NASA Astrobiology Program. All additional expenses associated with documenting your expedition will be covered.

If your team is looking to conduct field work in the next year and would like to participate in this series, please contact me here: mike.toillion@nasa.gov.