Posted byAaron Gronstal

NASA is committed to bringing everyone along as it explores the cosmos for a greater understanding of the Universe and our place in it. NASA’s exploration is a humanity-scale endeavor, and sharing in the discoveries, knowledge, and inspiration it generates is a human right. It transcends race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status, and has the power to uplift everyone. Such is the mission of the Astrobiology for the Incarcerated (AfI) initiative, which brings astrobiology lectures and programs into correctional facilities in the United States.

Education is fundamentally an agent for transformation. There is perhaps no place more ripe with transformative potential than a prison or jail. Using the stories astrobiology tells of our origins and the search for life elsewhere, AfI sparks curiosity and the desire to learn more in one of the most isolated and marginalized populations in America, incarcerated adults and youth.

Girls in a Juvenile Justice Service facility in Utah play the AstrobioBound! game.Image credit: NASA.

Overlooked Science Learners

There are roughly 2.3 million Americans currently incarcerated1 in the United States, and incarceration rates are racially disproportionate: 57 percent of inmates are African American or Hispanic even though they make up only 29 percent of the total US population. There is little to no science education programming offered in correctional facilities, and misinformation is prevalent. However, studies have shown that this population has the time, desire, and ability to learn.2 The AfI program seeks to inspire them to identify as science learners and contribute to a scientifically engaged, productive future.

Studies show educational programs of all types play a key role in helping ensure that incarcerated individuals do not become repeat offenders. Roughly 600,000 inmates are released each year,3 and 52 percent return to prison within three years.4 This rate of return is virtually unchanged over the past 10 years. A sweeping study commissioned by the Bureau of Justice Assistance in 2013 looked at the impact of a wide range of educational programs such as adult basic education, high school/General Educational Development (GED), postsecondary education, vocational training, and informal programs.5 The study found that exposure to these types of programs reduced the probability of recidivism by 13 percentage points (43 percent less likely to return) and increased the probability of post-release employment by 13 percent.

Early on in the AstrobioBound! game, incarcerated youth must decide what kind of mission their team will send to explore our Solar System and search for life – orbiter, lander, or rover.Image credit: NASA.

Strength through Partnership

Begun in 2016, AfI is a partnership between NASA’s Astrobiology Program, the Initiative to Bring Science Programs to the Incarcerated (INSPIRE) at the University of Utah, and the Sustainability in Prisons Project (SPP) at The Evergreen State College in Washington. AfI builds on more than a decade of pioneering work at INSPIRE and SPP, which built and sustains conservation-based scientific programs to prisons in Washington and Utah. The mission of AfI is to bring the excitement and importance of astrobiology research and discoveries to incarcerated learners across America. In doing so, the program strives to inspire individuals as science learners, and to help them develop a scientifically engaged, productive future.

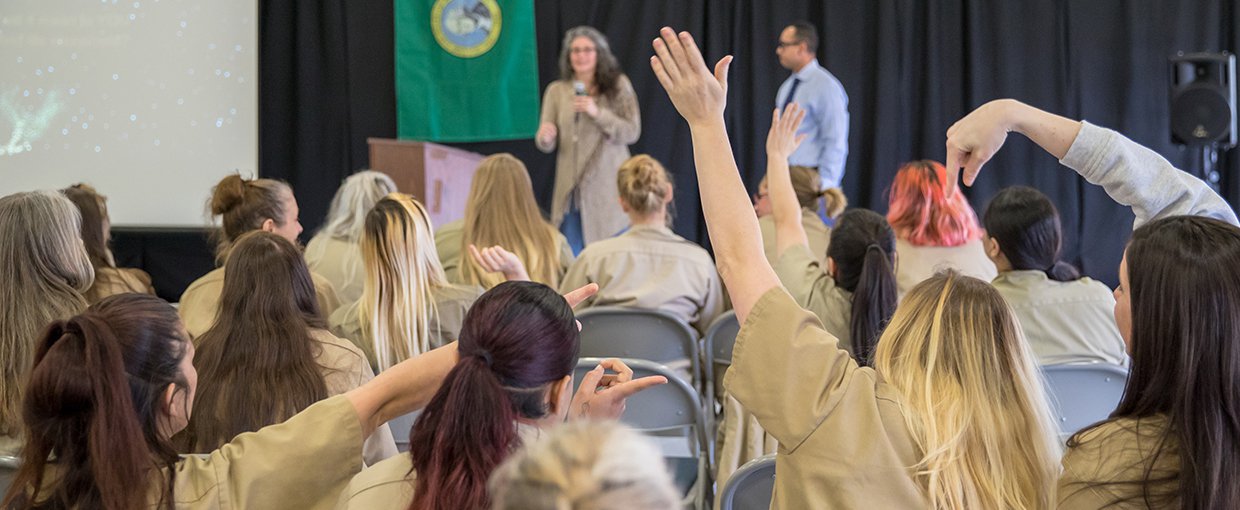

Dr. Drew Gorman Lewis of the University of Washington talks about his astrobiology research with incarcerated women in Washington.Image credit: NASA.

From December, 2017 through March, 2019, more than 1,400 adults (men and women) and more than 300 youth in 26 facilities across four states (Utah, Wash., Ohio, Fla.) participated in AfI programs. The AfI team delivered programs for adult men and women, and youth of both genders. For the youth, a lesson plan called Astrobiobound!, developed by education specialists at Arizona State University, was implemented. This game challenges teams of students to create a mission concept that will search for life in our Solar System, and configure an optimal payload against an assigned budget. It balances the roles of scientists and engineers, and promotes teamwork skills.

After a lecture in Washington, an incarcerated woman has a burning question.Image credit: NASA.

For the adults, lectures were given in the following locations:

- Four lectures for adults (men and women) in one prison and one jail

- Six hands-on programs for youth in six juvenile facilities

- Five lectures for adults (men and women) in five prisons

- Five lectures for adults (men and women) in five prisons

- One hands-on program for youth in one juvenile facility

- Six lectures for adults (men and women) in six prisons

- One hands-on program for youth in one juvenile facility

Boys in a Juvenile Justice Service facility in Washington play the AstrobioBound! game.Image credit: NASA.

The lectures for adults varied from one to three hours, and included lengthy discussions and questions. A 10-page handout was generated to reflect the content of the lectures. Each lecture was given in three parts – starting with “A Story of Creation,” moving through “A Story of Adaptation,” and finishing with “A Story of Exploration” – and wove them together into a story of our origins and search for life elsewhere.

A Thematic Approach

There are clear themes or concepts resident in this story that go beyond the content itself. The knowledge that the atoms that make up our Earth, and our very selves, were made in a star that lived and died long ago intimately connects us not only to the Universe and its cyclical processes, but also inextricably and immutably to the Solar System, the Earth, and to one another. Looking at the process of stellar nuclear fusion, the process by which most atoms heavier than Hydrogen were made, we can see creative potential in one of the harshest environments imaginable, the hyper-pressured core of a star.

Dr. Jackie Goordial from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences receives a question from an inmate during her lecture at a prison in Ohio.Image credit: NASA.

Planetary system formation as a phenomenon concurrent with star formation shows us that all the material in the star, planets, moons, asteroids, comets, etc. in our (and any given) solar system all formed from a common source (nebulae, giant molecular clouds) and according to the same processes. Herein lies more evidence of connectivity and relationship. If we find life elsewhere in the Solar System or the Universe, we’ll be related to it in this way as well.

As humans we think of the conditions in which early life may have emerged as “extreme,” such as the high temperatures of hot springs or vents, the crushing pressures and lack of sunlight on the seafloor, an atmosphere without free oxygen, bombardments at the surface, etc. Astrobiologists investigate such extreme environments here on the modern Earth, and study how life innovated and adapted in order for it to survive and thrive in these environments.

Astrobiology looks at the co-evolutionary relationship between life and Earth, and sees times when the environmental conditions presented life with challenges. Life innovated new biochemical strategies to cope with these challenges and, in doing so, influenced the environment in turn. This is perhaps most perfectly illustrated by the microbial invention of oxygenic photosynthesis roughly 2.5 billion years ago, through which oxygen was put into the atmosphere, catastrophic for some life forms, but likely paving the way for multicellular life and the Cambrian explosion.

Daniella Scalice of NASA’s Astrobiology Program delivers an astrobiology lecture at a prison in Ohio.Image credit: NASA.

In looking at the origin and evolution of life in this way, the themes of life’s resiliency, tenacity, and ability to innovate new strategies—under environmental pressure—to make a living and grow are clear. Time and again we can see the theme of creative potential in times of disruption, adverse conditions, and even catastrophe, as well as the idea of cause/effect and the relational nature of the Universe.

With respect to these themes, it stands to reason that our actions have consequences for which we must take responsibility. There is perhaps no place more exemplary of consequences than a prison or jail. There is also perhaps no place richer with transformative potential.

Interconnectedness and relationality can show us the way to respect and stewardship. If we impact or harm one part of the system, there will be reverberations throughout the system, and we will eventually feel the repercussions ourselves. This has implications in how we approach the discovery of life elsewhere—will we see it as other, as unrelated, or embrace it as family and strive to protect and preserve it? There are implications, too in how we behave toward our planet, and most importantly, how we treat one another. These themes and lessons are highlighted in the lecture programs for adults.

Dr. Nalini Nadkarni, founder of INSPIRE (Initiative to Bring Science Programming to the Incarcerated) at the University of Utah, visits with an inmate after a lecture in Florida.Image credit: NASA.

Next Steps

In compliance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) permissions, a robust evaluation plan allowed for pre/post data to be gathered to assess adult participant impacts in the areas of knowledge content gain, and attitudinal shifts in value of science and science identity. The findings are still being analyzed, but preliminary conclusions point to positive impacts in all categories.

The NASA Astrobiology Program will continue AfI through continued lectures and new, modular courses for adults delivered remotely by astrobiologists around the country. More and expanded hands-on programs for youth and those who educate them will be included as well.

Dr. Jamie Foster of the University of Florida answers questions during a break in her lecture at a prison in Florida.Image credit: NASA.

References

(1) Carson, 2015; Kirk, 2015; Minton & Zeng, 2015

(2) Nadkarni, N., J. Morris, 2018

(3) Carson & Golinelli, 2013

(4) Durose, Cooper, & Snyder, 2014

(5) Davis, L., Bozick, R., Steele, J., Saunders, J., Miles, J., 2013