The first exoplanets were all found using the radial velocity method of measuring the “wobble” of a star — movement caused by the gravitational pull of an orbiting planet.

Radial velocity has been great for detecting large exoplanets relatively close to our solar system, for assessing their mass and for finding out how long it takes for the planet to orbit its host star.

But so far the technique has not been able to identify and confirm many Earth-sized planets, a primary goal of much planet hunting. The wobble caused by the presence of a planet that size has been too faint to be detected by current radial velocity instruments and techniques.

However, a new generation of instruments is coming on line with the goal of bringing the radial velocity technique into the small planet search. To do that, the new instruments, together with their telescopes. must be able to detect a sun wobble of 10 to 20 centimeters per second. That’s quite an improvement on the current detection limit of about one meter per second.

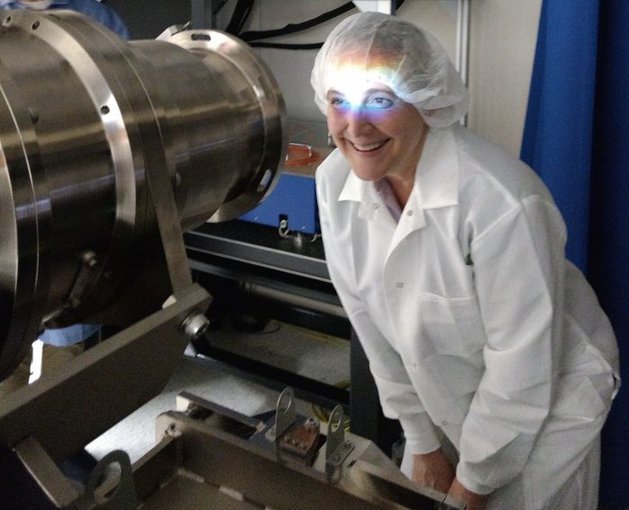

The spectrum from the EXtreme PREcision Spectrometer (EXPRES) shines on Yale astronomy professor Debra Fischer, who is PI of the project. EXPRES will find many Earth-size planets via the radial velocity method — something that has never been done.Image credit: Ryan Blackman/Yale.

At least three of these ultra high precision spectrographs (or sometimes called spectrometers) are now being developed or deployed. The European Southern Observatory’s ESPRESSO instrument has begun work in Chile; Pennsylvania State University’s NEID spectrograph (with NASA funding) is in development for installation at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona; and the just-deployed EXPRES spectrograph put together by a team led by Yale University astronomers (with National Science Foundation funding) is in place at the Lowell Observatory outside of Flagstaff, Arizona.

The principal investigator of EXPRES, Debra Fischer, attended the recent University of Cambridge Exoplanets2 conference with some of her team, and there I had the opportunity to talk with them. We discussed the decade-long history of the instrument, how and why Fischer thinks it can break that 1-meter-per-second barrier, and what it took to get it into attached and working.

One of the earliest and most difficult obstacles to the development of EXPRES, Fischer told me, was that many in the astronomy community did not believe it could work.

Their view is that precision below that one meter per second of host star movement cannot be measured accurately. Stars have flares, sunspots and a generally constant churning, and many argue that the turbulent nature of stars creates too much “noise” for a precise measurement below that one-meter-per-second level.

Yet European scientists were moving ahead with their ESPRESSO ultra high precision instrument aiming for that 10-centimeter-per-second mark, and they had a proven record of accomplishing what they set out to do with spectrographs.

In addition to the definite competiti0n going on, Fisher also felt that radial velocity astronomers needed to make that leap to measuring small planets “to stay in the game” over the long haul.

She arrived at Yale in 2009 and led an effort to build a spectrograph so stable and precise that it could find an Earth-like planet. To make clear that goal, the instrument is at the center of a project called “100 Earths.”

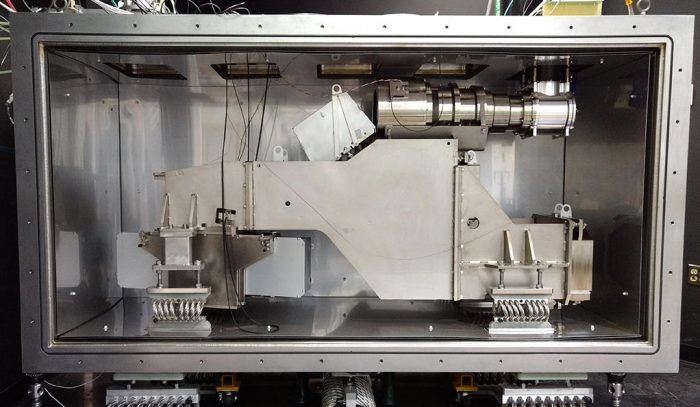

EXPRES in its vacuum-sealed chamber at the Lowell Observatory. will help detect Earth-sized planets in neighboring solar systems.Image credit: Ryan Blackman/Yale.

Building on experience gained from developing two earlier spectrographs, Fischer and colleagues began the difficult and complicated process of getting backers for EXPRES, of finding a telescope observatory that would house it (The Discovery Channel Telescope at Lowell) and in the end adapting the instrument to the telescope.

And now comes the actual hard part: finding those Earth-like planets.

As Fischer described it: “We know from {the Kepler Telescope mission} that most stars have small rocky planets orbiting them. But Kepler looked at stars very far away, and we’ll be looking at stars much, much closer to us.”

Nonetheless, those small planets will still be extremely difficult to detect due to all that activity on the host suns.

The 4.3 meter Discovery Channel Telescope in the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. The photons collected by the telescope are delivered via optical fiber to the EXPRES instrument.Image credit: Boston University.

Spectrographs such as EXPRES are instruments astronomers use to study light emitted by planets, stars, and galaxies.

They are connected to either a ground-based or orbital telescope and they stretch out or split a beam of light into a spectrum of frequencies. That spectrum is then analyzed to determine an object’s speed, direction, chemical composition, or mass. With planets, the work involves determining (via the Doppler shift seen in the spectrum) whether and how much a sun is moving to and away from Earth due to the pull of a planet.

As Fisher and EXPRES postdoctoral fellow John Brewer explained it, the signal (noise) coming from the turbulence of the star is detectably different from the signal made by the wobble of a star due to the presence of an orbiting planet.

While these differences — imprinted in the spectrum captured by the spectrograph — have been known for some time, current spectrographs haven’t had sufficient resolving power to actually detect the difference.

If all works as planned for the EXPRES, Espresso and NEID spectrographs, they will have that necessary resolving power and so can, in effect, filter out the noise from the sun and identify what can only come from a planet-caused wobble. If they succeed, they provide a major new pathway to for astronomers to search for Earth-sized worlds.

“This is my dream machine, the one I always wanted to build,” Fischer said. “I had a belief that if we went to higher resolution, we could disentangle (the stellar noise from the planet-caused wobble.)

“I could still be wrong, but I definitely think that trying was the right choice to make.”

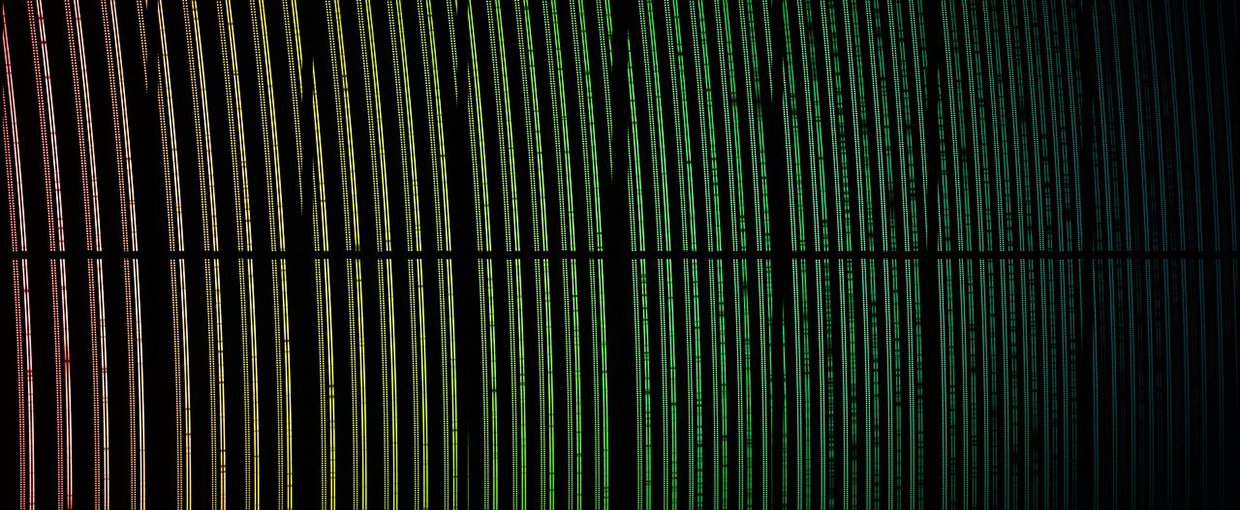

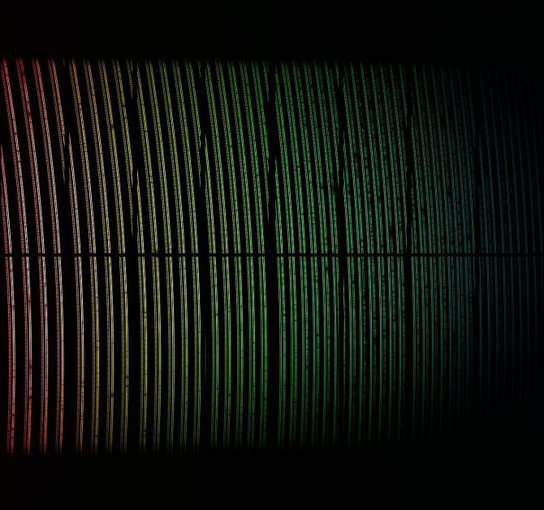

This image shows spectral data from the first light last December of the ESPRESSO instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. The light from a star has been dispersed into its component colors. This view has been colorised to indicate how the wavelengths change across the image, but these are not exactly the colors that would be seen visually.Image credit: ESO/ESPRESSO.

While Fischer and others have very high hopes for EXPRES, it is not the sort of big ticket project that is common in astronomy. Instead, it was developed and built primarily with a $6 million grant from National Science Foundation.

It was completed on schedule by the Yale team, though the actual delivering of EXPRES to Arizona and connecting it to the telescope turned out to be a combination of hair-raising and edifying.

Twice, she said, she drove from New Haven to Flagstaff with parts of the instrument; each trip in a Penske rental truck and with her son Ben helping out.

And then when the instrumentation was in process late last year, Fischer and her team learned that funds for the scientists and engineers working on that process had come to an end.

She was desperate, and sent a long-shot email to Francesco Pepe of University of Geneva, the lead scientist and wizard builder of several European spectrographs, including ESPRESSO. In theory, he and his instrument — which went into operation late last year at the ESO Very Large Telescope in Chile — will be competing with EXPRES for discoveries and acknowledgement.

Nonetheless, Pepe heard Fischer out and understood the predicament she was in. ESPRESSO had been installed and so he was able to contact an associate who freed up two instrumentation specialists who flew to Flagstaff to finish the work. It was, Fischer said, an act of collegial generosity and scientific largesse that she will never forget.

Fischer is at the Lowell observatory now, using the Arizona monsoon as a time to clean up many details before the team returns to full-time observing. She write about her days in an EXPRES blog. Earlier, in March after the instrumentation had been completed and observing had commenced, she wrote this:

“Years of work went into EXPRES and as I look at this instrument, I am surprised that I ever had the audacity to start this project. The moment of truth starts now. It will take us a few more months of collecting and analyzing data to know if we made the right design decisions and I feel both humbled and hopeful. I’m proud of the fact that our design decisions were driven by evidence gleaned from many years of experience. But did I forget anything?”