2015 Annual Science Report

VPL at University of Washington

Reporting | JAN 2015 – DEC 2015

VPL at University of Washington

Reporting | JAN 2015 – DEC 2015

Understanding Past Environments on Earth and Mars

Project Summary

In this task we performed research to understand the evolution of habitable environments on Earth and Mars, both of which serve as potential analogs for habitable environments on extrasolar planets. We are expanding this line of work from past reports to span the entire histories of both planets. On Earth, we have sought to understand environments and time periods spanning the origins of life to the effects of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions on modern-day climate cycles. On Mars, we focus on the ancient conditions that could have allowed liquid water to be stable at the surface; on modern Mars, we focus on the debate on the presence, amount, and variability of methane in the Martian atmosphere.

Project Progress

In this task we performed research to understand the evolution of habitable environments on Earth and Mars, both of which serve as potential analogs for habitable environments on extrasolar planets. We are expanding this line of work from past reports to span the entire histories of both planets. On Earth, we have sought understanding spanning from the origins of life to the effects of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions on modern-day climate cycles. On Mars, we focus on the ancient conditions that could have allowed liquid water to be stable at the surface; on modern Mars, we focus on the debate on the presence, amounts, and variability of methane in the Martian atmosphere.

Our work this year revisits hypotheses on the origin of life on Earth and the geological environment at life’s origin. Baross and colleague proposed a concept for a ribofilm in which RNA’s origin-of-life role would have been like a slowly changing platform than a spontaneous moment in time when a self-replicator arose. This paper linked the RNA world to realistic early Earth settings for the origin of life. It also presented a testable benchmark for attaining the hallmark characteristic of all Earth life: “the unity of biochemistry”. Baross and Anderson also surveyed the biogeography and ecology of deep sea hydrothermal vents, a potential site for the origin of life (Anderson et al., 2015). Keller, Black and grad student Gordon worked on the role of fatty acid membranes on the origin of life, and continue to explore self-assembly and the origin of life. Additionally, Sleep published a review of the tectonic history of the Earth, including a discussion of the conditions for the origin and evolution of early life on Earth, biological effects on global geological processes, and other concepts of high relevance to astrobiology (Sleep, 2015b).

However, most of our work this year focused on the period after the origins of life, but prior to the rise of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere. This included a paper by Smith, Catling and colleagues (Pecoits et al., 2015), which demonstrated that photosynthesis which does not produce oxygen was likely present to account for iron formations formed 3.8 Ga (Ga = billions of years ago). Iron formation deposition informs us about major changes in the biosphere and atmosphere; this analysis suggests the presence of photosynthetic life at the time of the very earliest sedimentary rock record on Earth. A separate nitrogen isotopic study by Stüeken, Buick and colleagues (Stüeken et al., 2015a) showed that the process by which biology incorporated nitrogen had evolved by 3.2 Ga; the implication is this process is ancient and potentially not very difficult to evolve, and so could plausibly exist elsewhere. This work is synergistic with separate work by Stüeken, Buick and colleague (Stüeken et al., 2015b) on the likely alkalinity of Archean lakes, which may serve as good analogs for the alkaline lake environments Curiosity is discovering on Mars. Nitrogen isotope studies show that these were a source of ammonia to the atmosphere; a planet with many such lakes might have a flux significant enough to allow this gas to accumulate to detectable levels.

Our work on biological nitrogen incorporation also has significant implications for the amount of nitrogen in Earth’s atmosphere. We continued VPL’s work on understanding the amount of nitrogen—and the total pressure—of Earth’s ancient atmosphere. This included the development of a new proxy for the planet’s total atmospheric pressure (Som et al., accepted), some reanalysis of previously used proxies for pressure (Kavenagh and Goldblatt, 2015), research on the planet’s nitrogen budget over time (Johnson and Goldblatt, 2015), and the development of a semi-analytic treatment of Earth’s ancient nitrogen cycle (Goldschmidt abstract: http://goldschmidtabstracts.info/2015/487.pdf ).

Given those constraints on pressure, we studied Earth’s ancient climate. This included studies of the maximum amount of warming that different greenhouse gases can deliver (Byrne and Goldblatt, 2015), and 1D simulations of the maximum temperatures that could have been achieved given geological constraints. Buick and colleagues (Bradley et al., 2015) used paleomagnetic analysis showed to show that latitudinal climatic zonation was roughly the same 3.5 billion years ago as it is now, implying that atmospheric circulation patterns were similar and that the early Earth had an axial dipole magnetic field, as it does today.

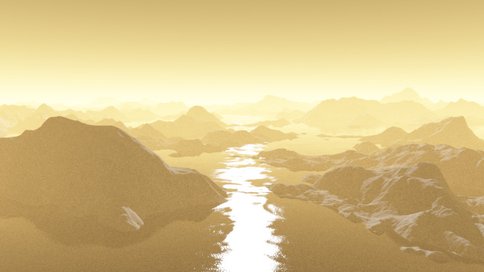

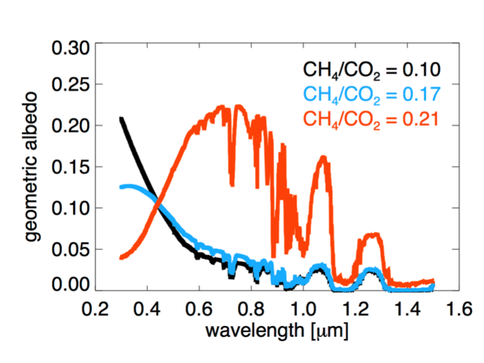

Prior to the rise of oxygen, Earth’s climate may have been driven by the thickness of an organic haze, which appears to have been intermittently thick prior to the rise of oxygen. Our work this year supported this hypothesis by expanding the global extent of the geological data sets that are consistent with such a haze (Izon, et al., 2015). In a separate study, Arney, Domagal-Goldman, Meadows, Schwieterman, Charnay and colleagues (Arney et al., submitted) simulated this haze to examine its climatic effects, and studied its spectral implications for future exoplanet observations (Figure 2).

The oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans in the Proterozoic is one of the great unsolved problems in Earth’s history. In an attempt to determine the mechanism for oxygen’s rise, Krissansen-Totton, Buick and Catling analyzed Earth’s carbon isotope record over the last 3.6 billion years to monitor carbon burial rates. This work showed that although this record varied over time, it did not vary enough to explain the rise in atmospheric oxygen at 2.4 Ga (Krissansen-Totton, et al., 2015). The onset of biological oxygen production is another key piece of evidence required to determine the circumstances that led to the rise rise of atmospheric oxygen. Evidence that oxygen production first occurred hundreds of millions of years before oxygen rose in the atmosphere had been determined from the presence of hydrocarbon biomarker molecules in organic-rich shales. However, VPL team member Buick and colleagues from other NAI Lead Team (French et al., 2015) overturned these results by conducting organic geochemical analysis of a new Archean drill-core that was obtained and sampled under exceptionally clean conditions. This new research finds no biomarkers in strata that had previously been thought to contain them, suggesting that the hydrocarbons previously identified as molecular fossils were instead contaminants introduced during collection.

Stüeken, Buick, and colleague continued to look at geochemical proxies for and implications of the Earth’s rise of atmospheric oxygen. This includes work that suggests a spike in selenium weathering occurred during the brief ‘whiff’ of oxygen prior to its permanent appearance in the atmosphere (Stüeken et al., 2015c). This has implications for atmospheric chemistry, continental weathering, and the chemistry of the oceans at the time. It also has implications for biological production of potential biosignature gases. This also led to work on the ability of one particular element—Se—both participate in novel biosignature species (Stüeken et al., 2015d) and to have revealed the redox state of the ocean during one of Earth’s past extinction events (Stüeken et al., 2015e).

All of this work is being leveraged by our team on multiple spaceflight projects. This includes a series of papers (Freissinet et al., 2015; Mahaffy and Conrad, 2015; Mahaffy et al., 2015; Stern et al., 2015; and Webster et al., 2015) from the MSL/Curiosity Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument team that included contributions from VPL team members Conrad and Domagal-Goldman. The experience of these two VPL team members, developed by studying Earth history, informed this work. This is also exemplified by papers that did not come from the MSL/SAM team, but still leveraged VPL’s expertise as developed by our Earth Through Time task. For example, this year we published a paper on the sustainability of H2-dominated greenhouses on early Mars, which leverages both numerical and conceptual models that were previously developed by our team for simulations of the rise of oxygen on early Earth. Finally, we note that VPL contributed to both sides of a rigorous debate on the detection of methane (CH4) by the SAM/MSL team (Webster et al., 2015 and Zahnle, 2015).

-

PROJECT INVESTIGATORS:

-

PROJECT MEMBERS:

Giada Arney

Co-Investigator

Benjamin Charnay

Co-Investigator

Pamela Conrad

Co-Investigator

Colin Goldblatt

Co-Investigator

James Kasting

Co-Investigator

Victoria Meadows

Co-Investigator

Edward Schwieterman

Co-Investigator

Megan Smith

Co-Investigator

Eva Stüeken

Co-Investigator

Kevin Zahnle

Co-Investigator

Mark Claire

Collaborator

Sanjoy Som

Collaborator

Rika Anderson

Unspecified Role

Roy Black

Unspecified Role

-

RELATED OBJECTIVES:

Objective 1.1

Formation and evolution of habitable planets.

Objective 1.2

Indirect and direct astronomical observations of extrasolar habitable planets.

Objective 4.1

Earth's early biosphere.

Objective 4.2

Production of complex life.

Objective 5.1

Environment-dependent, molecular evolution in microorganisms

Objective 5.2

Co-evolution of microbial communities

Objective 6.1

Effects of environmental changes on microbial ecosystems