-

How Hot Were the Oceans When Life First Evolved?

June 05, 2017 / Written by: Charles Choi

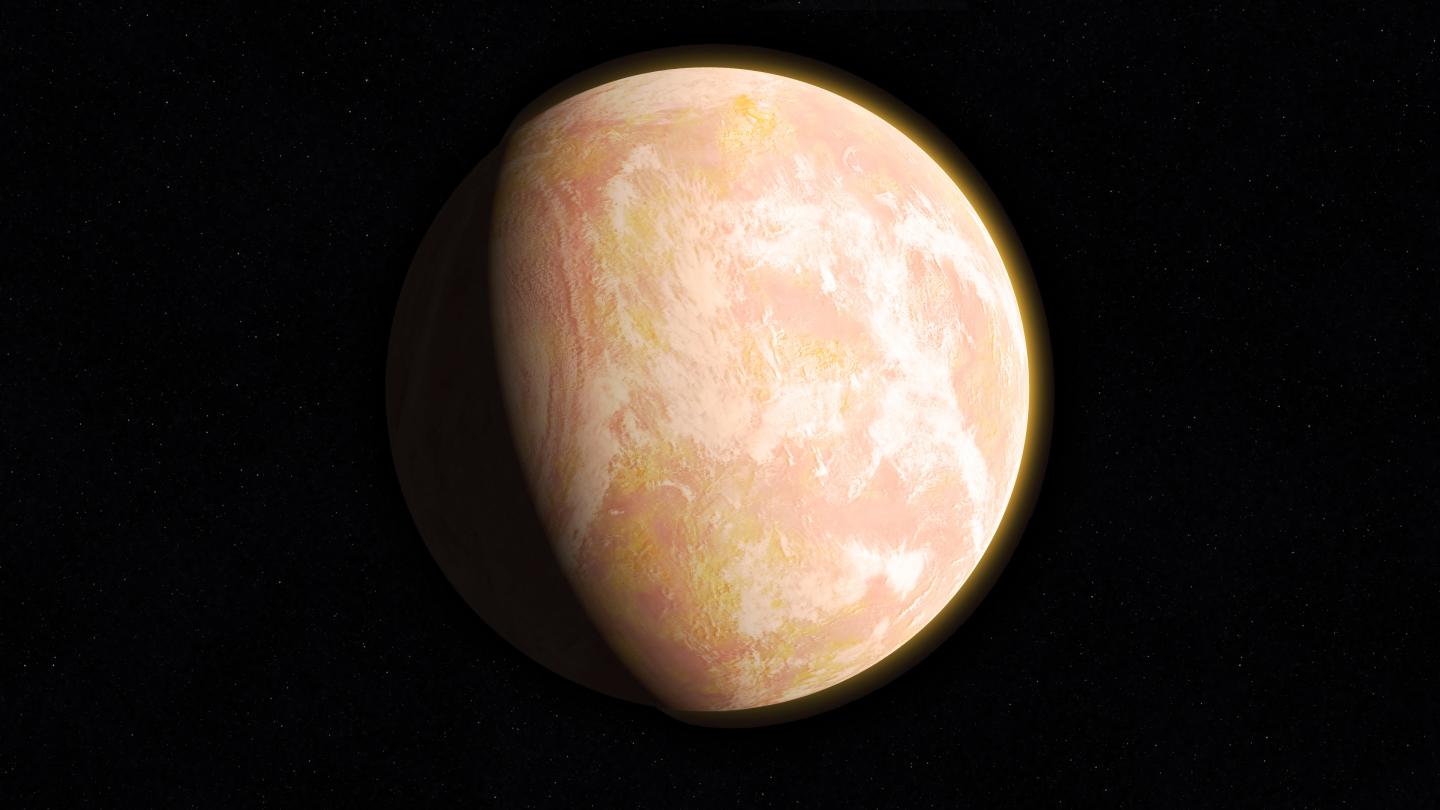

When haze built up in the atmosphere of Archean Earth, the young planet might have looked like this artist’s interpretation — a pale orange dot.We know little about Earth’s surface temperatures for the first 4 billion years or so of its history. This presents a limitation into research of life’s origins on Earth and also how it might arise on distant worlds as well.

Now researchers suggest that by resurrecting ancient enzymes they could estimate the temperatures in which these organisms likely evolved billions of years ago. The scientists recently published their findings in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We need a better understanding of not only how life first evolved on Earth, but how life and the Earth’s environment co-evolved over billions of years of geological history,” said lead author Amanda Garcia, a paleogeobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “A similar co-evolution seems certain to be the case for any life elsewhere in the Universe.”

Garcia and her colleagues focused on the history of Earth’s surface temperatures. Rocks offer many clues to deduce temperatures over the last 550 million years in the Phanerozoic Era, when complex, multicellular life took off, including that of humans. However, few such “paleothermometers” exist for the earlier Precambrian Era, spanning the Earth’s formation 4.6 billion years ago and the rise of life.

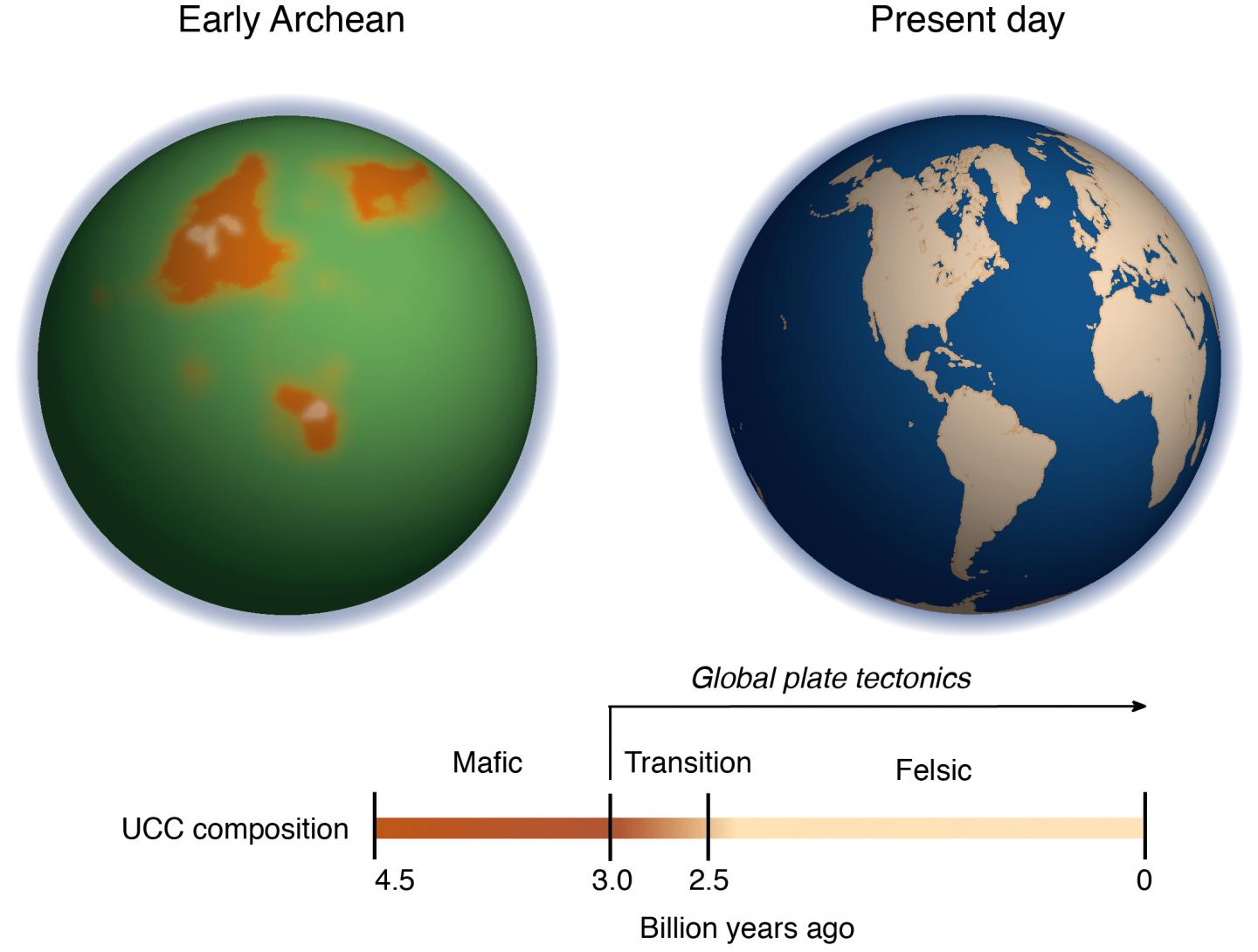

The image on the left depicts what Earth might have looked like more than 3 billion years ago in the early Archean. The orange shapes represent the magnesium-rich proto-continents before plate tectonics started, although it is impossible to determine their precise shapes and locations. The ocean appears green due to a high amount of iron ions in the water at that time. The timeline traces the transition from a magnesium- rich upper continental crust to a magnesium-poor upper continental crust. Credit: Ming Tang/University of MarylandEarlier geological evidence has suggested that 3.5 billion years ago, during the Archean Eon, the oceans were 131o to 185o F (55o to 85o C). They cooled dramatically to current average temperatures of 59o F (15o C). Scientists made these estimates by examining oxygen and silicon isotopes in marine rocks.Quartz-rich rocks in the seabed, known as cherts, have higher levels of the heavier oxygen-18 and silicon-30 isotopes as the seawater gets colder. In principle, the ratio of heavier to lighter oxygen and silicon isotopes can shed light on ancient temperatures.

But such paleo-thermometers do not adequately take into account how these rocks or the ocean might have changed over the course of billions of years. Perhaps the isotopic ratios in seawater varied over time in response to physical or chemical alterations, such as water flows off the land or from hydrothermal vents.

Given the uncertainties, Garcia and her colleagues sought an independent measurement of seawater temperatures in the Precambrian that centers on the behavior of biological molecules. The scientists examined an enzyme known as nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK), which helps manipulate the building blocks of DNA and RNA, as well as many other roles. Versions of this protein are found in virtually all living organisms, and were likely vital to many extinct organisms as well. Previous research found a correlation between the optimal temperatures of protein stability and an organism’s growth.

By comparing the molecular sequences of versions of NDK in a variety of contemporary species, researchers can reconstruct the versions of NDK that might have been present in their common ancestors. By synthesizing these reconstructions, scientists can experimentally test these “resurrected” ancient proteins to find the temperature that stabilizes the protein and deduce from that the likely temperature that supported the ancient organism.

Microbial reefs called stromatolites are examples of biological structures found as far back as 3.7 billion years ago.Scientists estimate when ancient enzymes might have existed by looking at their closest living relatives of their host organism. The greater the number of differences in the genetic sequences of these relatives, the longer ago their last common relative likely lived. Scientists use these differences to gauge the age of biomolecules such as the reconstructions of NDK.

Previous research had reconstructed ancient enzymes to deduce past temperatures, but some of these enzymes may have come from organisms that lived in unusually hot environments, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which would not be representative of the wider ocean. Instead, Garcia and her colleagues sought to reconstruct NDK from land plants and photosynthetic bacteria living in the upper sunlit depths of oceans, presumably far away from boiling hot springs.

Their research suggests that Earth’s surface cooled from roughly 167o F (75o C) about 3 billion years ago to roughly 95o (35o F) about 420 million years ago. These findings are consistent with previous geological and enzyme-based results.

Garcia said such a dramatic cooling is hard to fathom, emphasizing how scientists need to remember how different conditions were in the past when figuring out how life evolved over time.

“It requires a lot of effort to envision a world that does not seem to fit with the common sense of our current Earth conditions.”

Future research could reconstruct versions of NDK from more organisms, as well as other enzymes, giving more evidence to support the method. Such research could help “in solving big questions about the early evolution of life and Earth’s environment,” she said.

The participation of study co-author J. William Schopf, founder of the Center for the Study of Evolution and the Origin of Life at the University of California, Los Angeles, was supported by his membership in the NASA Astrobiology Institute’s Wisconsin Astrobiology Research Consortium.

Source: [astrobio.net]

- The NASA Astrobiology Institute Concludes Its 20-year Tenure

- Global Geomorphologic Map of Titan

- Molecular Cousins Discovered on Titan

- Interdisciplinary Consortia for Astrobiology Research (ICAR)

- The NASA Astrobiology Science Forum Talks Now on YouTube

- The NASA Astrobiology Science Forum: The Origin, Evolution, Distribution and Future of Astrobiology

- Alternative Earths

- Drilling for Rock-Powered Life

- Imagining a Living Universe

- Workshops Without Walls: Astrovirology