May I please invite you to join me in the presence of one of the great natural phenomena and spectacles of our world.

Not only is it enthralling to witness and scientifically crucial, but it’s quite emotionally moving as well.

Why? Because what’s before me is a physical manifestation of one of the primary, but generally invisible, features of Earth that make life possible. It’s mostly seen in the far northern and far southern climes, but the force is everywhere and it protects our atmosphere and us from the parched fate of a planet like Mars.

I’m speaking, of course, of the northern lights, the Aurora Borealis, and the planet’s magnetic fields that help turn on the lights.

My vantage point is the far northern tip of Norway, inside the Arctic Circle. It’s stingingly cold in the silent woods, frozen still for the long, dark winter, and it’s always an unpredictable gift when the lights show up.

But they‘re out tonight, dancing in bright green and sometimes gold-tinged arches and spotlights and twirling pinwheels across the northerly sky. Sometimes the horizon glows green, sometimes the whole sky fills with vivid green streaks.

It can all seem quite other-worldly. But the lights, of course, are entirely the result of natural forces.

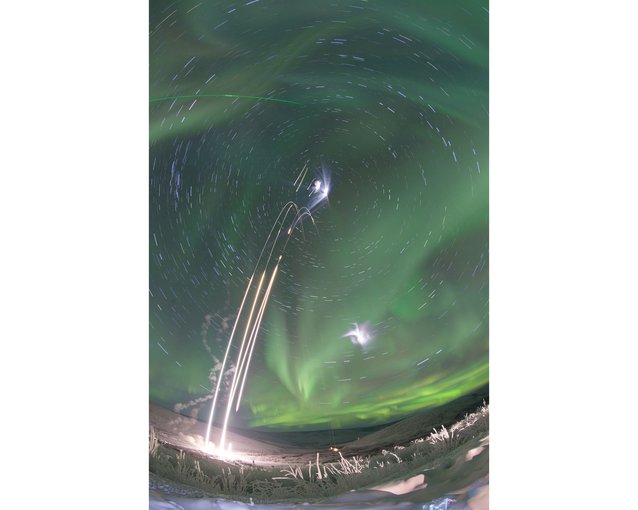

To study auroras, NASA suborbital sounding rockets launch from the Poker Flat Research Range in Alaska carrying the Mesosphere-Lower Thermosphere Turbulence Experiment (M-TeX) and Mesospheric Inversion-layer Stratified Turbulence (MIST).Image credit: NASA/Jamie Adkins.

It has been known for some time that the lights are caused by reactions between the high-energy particles of solar flares colliding in the upper regions of our atmosphere and then descending along the lines of the planet’s magnetic fields. Green lights tell of oxygen being struck at a certain altitude, red or blue of nitrogen.

But the patterns — sometimes broad, sometimes spectral, sometimes curled and sometimes columnar — are the result of the magnetic field that surrounds the planet. The energy travels along the many lines of that field, and lights them up to make our magnetic blanket visible.

Such a protective magnetic field is viewed as essential for life on a planet, be it in our solar system or beyond.

But a magnetic field does not a habitable planet make. Mercury has a weak magnetic field and is certainly not habitable. Mars also once had a strong magnetic field and still has some remnants on its surface. But it fell apart early in the planet’s life, and that may well have put a halt to the emergence or evolution of living things on the otherwise habitable planet.

I will return to some of the features of the northern lights and the magnetism is makes visible, but this is also an opportunity to explore the role of magnetism in biology itself.

This was a quasi-science for some time, but more recently it has been established that migrating birds and fish use magnetic sensors (in their beaks or noses, perhaps) to navigate northerly and southward paths.

Joseph Kirschvink, a geobiologist with Caltech and ELSI (the Earth-Life Science Institute in Tokyo) has been studying for decades the ways in which creatures from bacteria to humans use magnetic forces in their lives.Image credit: Caltech.

But did you know that bacteria, insects and mammals of all sorts appear to have magnetic compasses as well? They can read the magnetism in the air, or can read it in the rocks (as in the case of some sea turtles.) A promising line of study, pioneered by scientists including geobiologist Joseph Kirschvink of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) in Tokyo, is even studying potentially remnant magnetic senses in humans.

“There no doubt now that magnetic receptors are present in many, many species, and those that don’t have it probably lost it because it wasn’t useful to them,” he told me. “But there’s good reason to say that the magnetic sense was most likely one of the earliest on Earth.”

But how does it work for animals? How do they receive the magnetic signals? This is a question of substantial study and debate.

One theory states that creatures use the iron mineral magnetite — that they can produce and consume – to pick up the magnetic signals. These miniature compass needles sit within receptor cells, either near a creature’s nose or in the inner ear.

Gum Boot Chiton (Cryptochiton stellari).Image credit: Jerry Kirkhart, Los Osos, Calif., (cc).

Another posits that magnetic fields trigger quantum chemical reactions in proteins called cryptochromes, which have been found in the retina. But no one has determined how they might send signals and information to the brain.

Kirschvink was part of a team that demonstrated bacteria’s use of Earth’s magnetic field back to the Archean era, 3 to 3.5 billion years ago. “My guess is that magnetism has had a major influence on the biosphere since then, via the biological ability to make magnetic materials.”

He said that when the sun is particularly angry and active, the geomagnetic storms that occur around the planet seem to interfere with these magnetic responses and that animals don’t navigate as well.

Kirschvink sees magnetism as a possibly important force in the origin of life. Magnetite that is lined up like beads on a chain has been detected in bacteria, and he says it may have provided an evolutionary pathway for structure that allowed for the rise of eukaryotes — organisms with complex cells, or a single cell with a complex structures.

Kirschvink and his team are in the midst of a significant study of the effects of geomagnetism on humans, and the pathways through which that magnetism might be used.

That’s rather a long way from some of the early biomagnetism discoveries, which involved the chiton. A mollusk relative of the snail and the limpet, the chiton holds on to rocks in the shallow water and uses its magnetite-covered teeth to scrape algae from rocks. The teeth are on a tongue-like feature called the radula and those teeth are capped with so much magnetite that a magnet can pick up the foot-long gumboot chiton, the largest of the species.

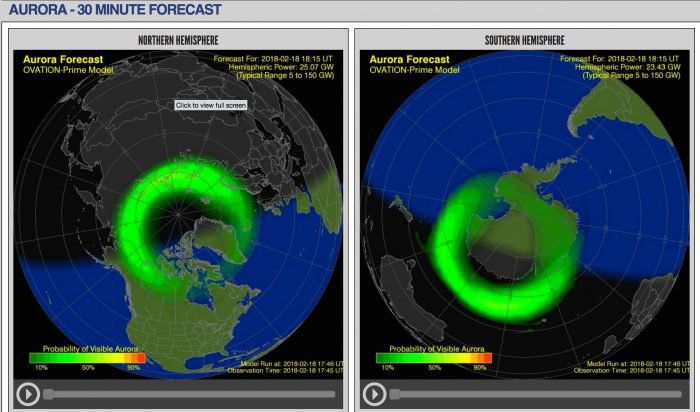

Models based on measuring solar flares, or coronal mass ejections, coming from sunspots that rotate and face Earth every 27 or 28 days. Summer months in the northern hemisphere often make the sky too light for the lights to be seen.Image credit: NOAA.

Back at most northern and southerly regions of the planet, where the magnetic field lines are most concentrated, the lights put on their displays for ever larger audiences of people who want to experience their presence.

We had part of one night of almost full sky action, with long arches, curves large and small, waves, spotlights , shimmers and curtains. It had the feel of a spectacular fireworks display, but magnified in its glory and power and, of course, entirely natural. (I hope to post images taken by others that night which, alas, were not captured by my camera because the battery froze in the 10 degree cold.)

Our grand night was one of the special ones when the colors (almost all greens, but some reds too) were so bright that their shapes and movements were easy to see with the naked eye.

Good cameras (especially those with batteries that don’t freeze) see and capture a much broader range of the northern light presence. The horizon, for instance, can appear just slightly green to the naked eye, but will look quite brightly green in an image.

Thanks to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Weather Service and NASA, forecasting when and where the lights are likely to be be active in the northern and southern (the Aurora Australis) polar regions.

This forecasting of space weather revolves around the the eruption of solar flares. The high-energy particles they send out collide with electrons in our upper atmosphere accelerate and follow the Earth’s magnetic fields down to the polar regions.

Aurora borealis image that a member of the Expedition 53 crew took on Sept. 15, 2017, from the International Space Station. These lights were seen over Canada while the station was near the highest point of its orbital path.Image credit: NASA GSFC/ESC.

In these collisions, the energy of the electrons is transferred to the oxygen and nitrogen and other elements in the atmosphere, in the process exciting the atoms and molecules to higher energy states. When they relax back down to lower energy states, they release their energy in the form of light. This is similar to how a neon light works.

The aurora typically forms 60 to 400 miles above Earth’s surface.

All this is possible because of our magnetic field, which scientists theorize was created and is sustained by interactions between super-hot liquid iron in the outer core of the Earth’s center and the rotation of the planet. The flowing or convection of liquid metal generates electric currents and the rotation of Earth causes these electric currents to form a magnetic field which extends around the planet.

If the magnetic field wasn’t present those highly charged particles coming from the sun, the ones that set into motion the processes that produce the Northern and Southern Lights, would instead gradually strip the atmosphere of the molecules needed for life.

This intimate relationship between the magnetic field and life led to me ask Kirschvink, who has been studying that connection for decades, if he had seen the northern or southern lights.

No, he said, he’d never had the chance. But if ever in the presence of the lights, he said he know exactly what he would do: take out his equipment and start taking measurements and pushing his science forward.