Last month, the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission released the most accurate catalogue to date of positions and motions for a staggering 1.3 billion stars.

Let’s do a few comparisons so we can be suitably amazed. The total number of stars you can see without a telescope is less than 10,000. This includes visible stars in both the northern and southern hemispheres, so looking up on a very dark night will allow you to count only about half this number.

The data just released from Gaia is accurate to 0.04 milli-arcseconds. This is a measurement of the angle on the sky, and corresponds to the width of a human hair at a distance of over 300 miles (500 km.) These results are from 22 months of observations and Gaia will ultimately whittle down the stellar positions to within 0.025 milli-arcseconds, the width of a human hair at nearly 680 miles (1000 km.)

OK, so we are now impressed. But why is knowing the precise location of stars exciting to planet hunters?

The reason is that when we claim to measure the radius or mass of a planet, we are almost always measuring the relative size compared to the star. This is true for all planets discovered via the radial velocity and transit techniques — the most common exoplanet detection methods that account for over 95% of planet discoveries.

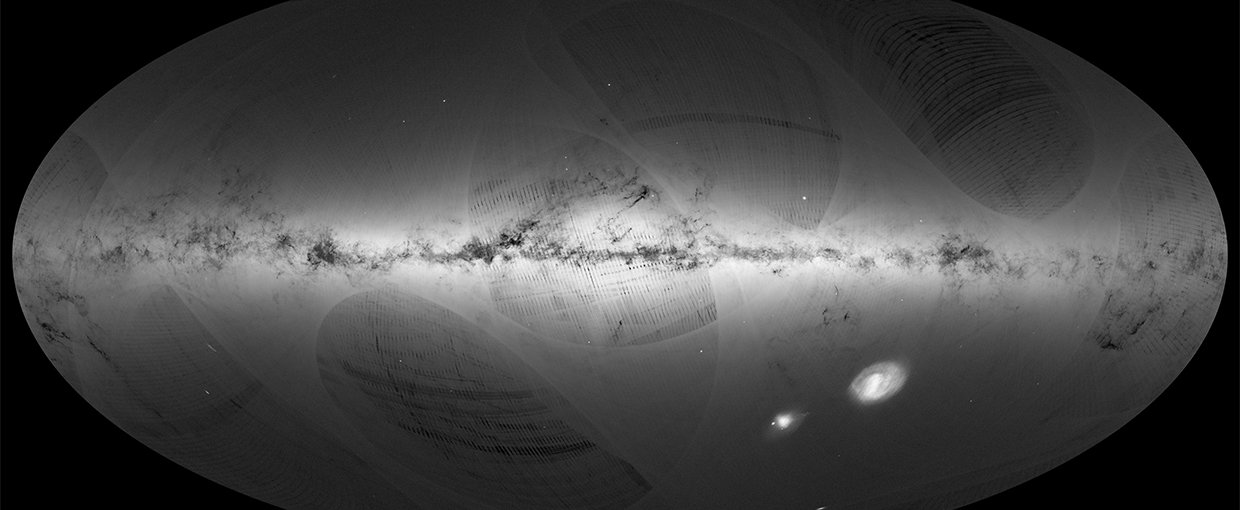

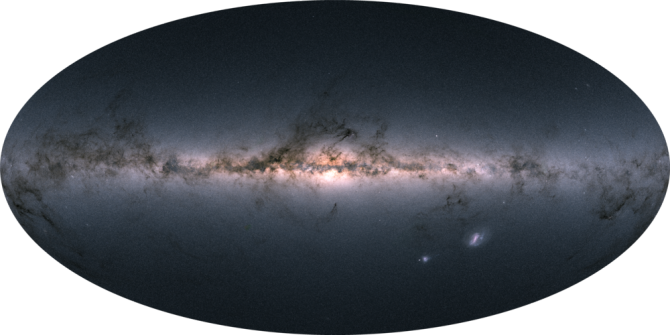

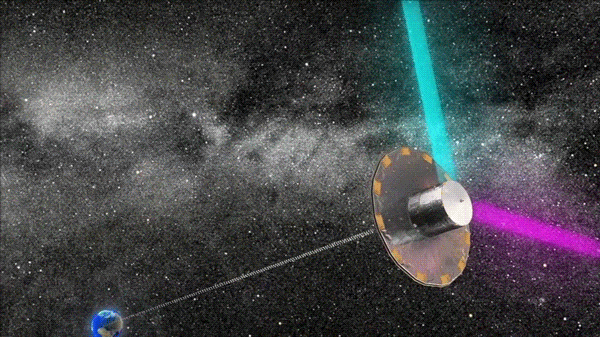

Gaia’s all-sky view of our Milky Way and neighboring galaxies.Image credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC.

It means that if we underestimate the star size, our true planet size may balloon from being a close match to the Earth to a giant the size of Jupiter. If this is true for many observed planets, then all our formation and evolution theories will be a mess.

The size of a star is estimated from its brightness. Brightness depends on distance, as a small, close star can appear as bright as a distant giant. Errors in the precise location of stars therefore make a big mess of exoplanet data.

This issue has been playing on the minds of exoplanet hunters.

In 2014, a journal paper authored by Fabienne Bastien from Vanderbilt University suggested that nearly half of the brightest stars observed by the Kepler Space Telescope are not regular stars like our sun, but actually are distant and much larger sub-giant stars. Such an error would mean planets around these stars are 20 – 30% larger than estimated, a particularly hard punch for the exoplanet community as planets around bright stars are prime targets for follow-up studies.

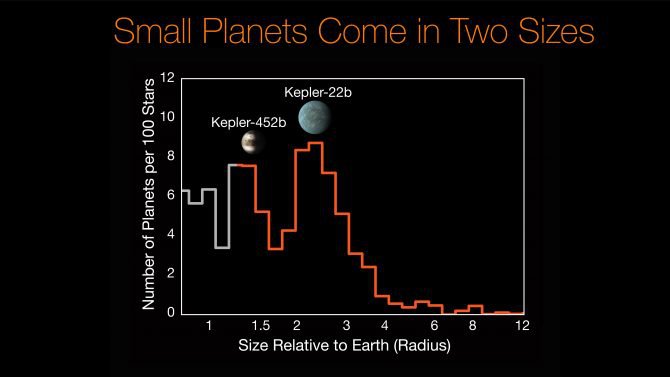

Previous improvements in the accuracy of the measured radii and other properties of stars have already proved their worth. In 2017, a journal paper led by Benjamin Fulton at the University of Hawaii revealed the presence of a gap in the distribution of sizes of super Earths orbiting close to their star. Planets 20% and 140% larger than the Earth appeared to be common, but there was a notable dearth of planets around twice the size of our own.

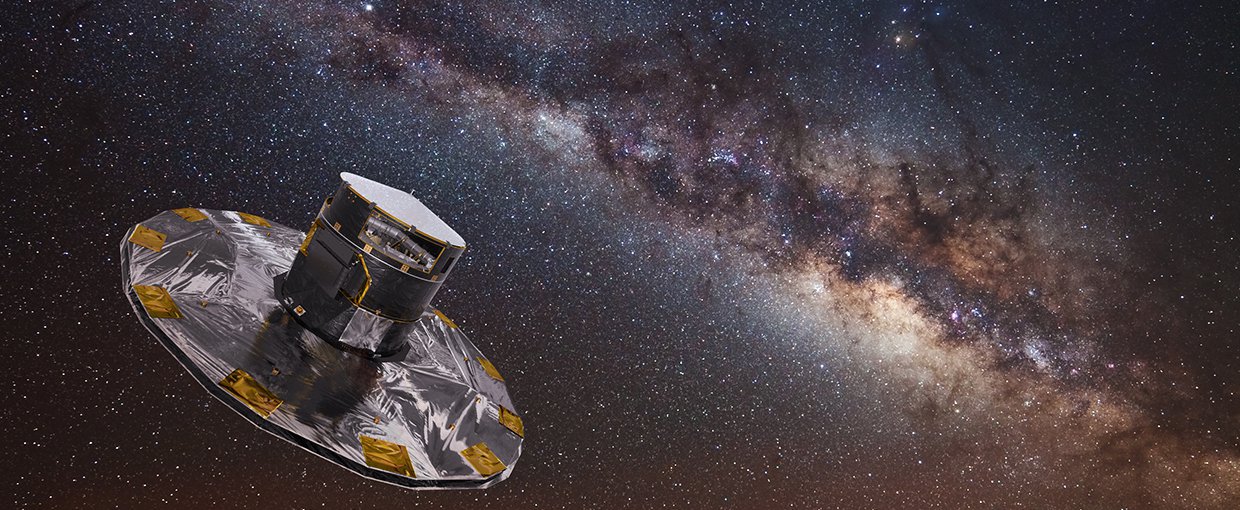

An artist’s impression of the Gaia spacecraft — which is on a mission to chart a three-dimensional map of our Milky Way. In the process it will expand our understanding of the composition, formation and evolution of the galaxy.Image credit: ESA/D. Ducros.

The most popular theory for this gap is that the peaks belong to planets with similar core sizes, but the planets with larger radii have deep atmospheres of hydrogen and helium. This would make the planets belonging to the smaller radii peak true rocky worlds, whereas the second peak would be mini Neptunes: the first evidence of a size distinction between these two regimes.

This split in the small planet population was spotted due to improved measurements of planet radii based on higher precision stellar observations made using the Keck Observatory. With a gap size of only half an Earth-radius, it had previously gone unnoticed due to the uncertainty in planet size measurements.

Both the concern of a significant error in planet sizes and the tantalizing glimpse at the insights that could be achieved with more accurate data is why Gaia is so exciting.

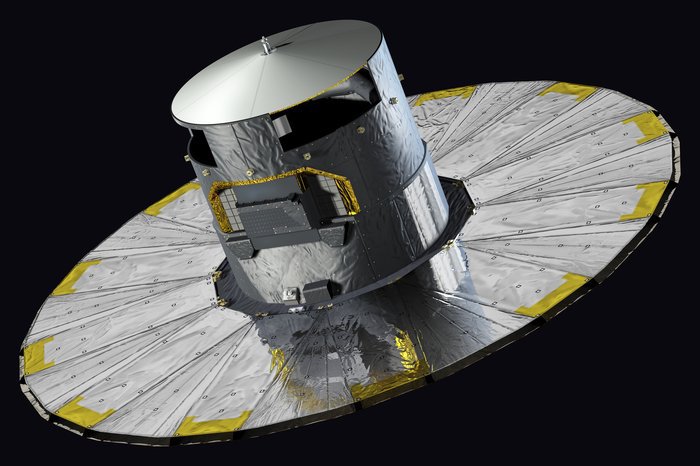

Launched on December 19, 2013, Gaia is a European Space Agency (ESA) space telescope for astrometry; the measurement of the position and motion of stars. The mission has the modest goal of creating a three-dimensional map of our galaxy to unprecedented precision.

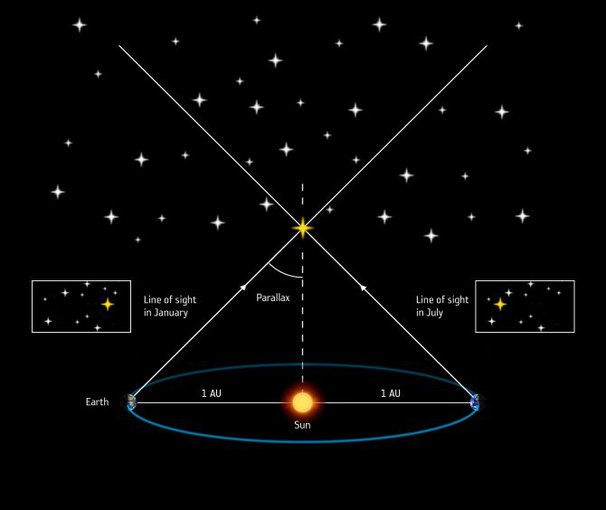

Gaia measures the position of stars using a technique known as parallax, which involves looking at an object from different perspectives.

Parallax is easily demonstrated by holding up your finger and looking at it with one eye open and the other closed. Switch eyes, and you will see your finger moves in relation to the background. This movement is because you have viewed your finger from two different locations: the position of your left eye and that of your right.

Super Earth planets with orbits of less than 100 days seem to come in two different sizes.Image credit: NASA/Ames/Caltech/University of Hawaii/B.J.Fulton.

The degree of motion depends on the separation between your eyes and the distance to your finger: if you move your finger further from your eyes, its parallax motion will be less. By measuring the separation of your viewing locations and the amount of movement you see, the distance to an object can therefore be calculated.

Since stars are far more distant than a raised finger, we need widely separated viewing locations to detect the parallax. This can be done by observing the sky when the Earth is on opposite sides of its orbit. By measuring how far stars seem to move over a six month interval, we can calculate their distance and precisely estimate their size.

This measurement was first achieved by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel in 1838, who calculated the distance to the star 61 Cygni. Bessel estimated the star was 10.3 light years from the Earth, just 10% lower than modern measurements which place the star at a distance of 11.4 light years.

However, measuring parallax from Earth can be challenging even with powerful telescopes. The first issue is that our atmosphere distorts light, making it difficult to measure tiny shifts in the position of more distant stars. The second problem is that the measured motion is always relative to other background stars. These more distant stars will also have a parallax motion, albeit smaller than stars closer to Earth.

As a result, the motion measured and hence the distance to a star, will depend on the parallax of the more distant stars in the same field of view. This background parallax varies over the sky, leaving no way on Earth of creating a consistent catalogue of stellar positions.

Parallax is the apparent shift in the position of stars as the Earth orbits the sun. It can be used to determine distances between stars.Image credit: ESA/ATG medialab.

These two conundrums are where Gaia has the advantage. Orbiting in space, Gaia simply avoids atmospheric distortion. The second issue of the background stars is tackled by a clever instrument design.

Gaia has two telescopes that point 106.4 degrees apart but project their images onto the same detector. This allows Gaia to see stars from different parts of the sky simultaneously. The telescopes slowly rotate so that each field of view is seen once by each telescope and overlaid with a field 106.4 degrees either clockwise or counter-clockwise to its position. The parallax motion of stars during Gaia’s orbit can therefore be compared both with stars in the same field of view, and with stars in two different directions.

Gaia repeats this across the sky, linking the fields of view together to globally compare stellar positions. This removes the problem of a parallax measurement depending on the motion of stars that just happen to be in the background.

The result is the relative position of all stars with respect to one another, but a reference point is needed to turn this into true distances. For this, Gaia compares the parallax motion to distant quasars.

Quasars are black holes that populate the center of galaxies and are surrounded by immensely luminous discs of gas. Being outside our Milky Way, the distance to quasars is so great that their parallax during the Earth’s orbit is negligibly small. Quasars are too rare to be within the field of view of most stars, but with stellar positions calibrated across the whole sky, Gaia can use any visible quasars to give the absolute distances to the stars.

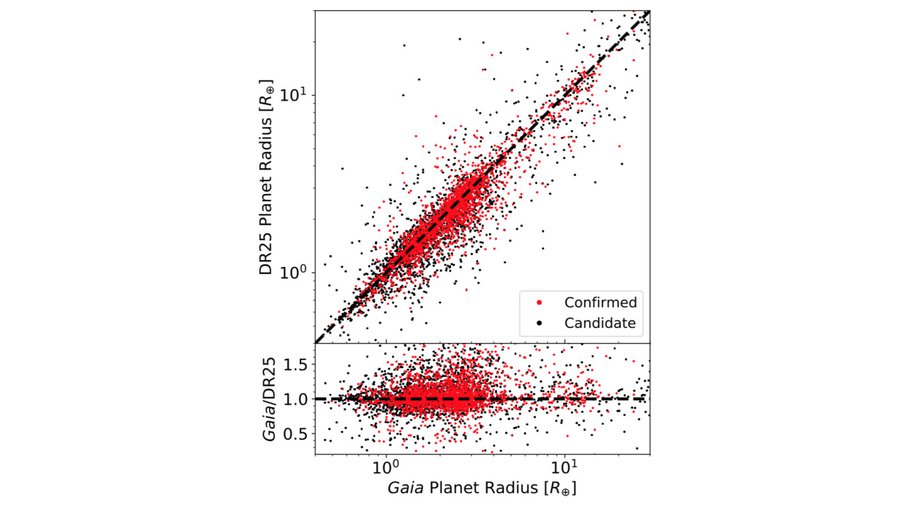

What did these precisely measured stellar motions do to the properties of the orbiting planets? Did our small worlds vanish or the intriguing division in the sizes of super Earths disappear?

This was bravely investigated in a journal paper this month led by Travis Berger from the University of Hawaii. By matching the stars observed by Kepler to those in the Gaia catalogue, Berger confirmed that the majority of bright stars were indeed sun-like and not the suspected sub-giant population. However, the more precise stellar sizes were slightly larger on average, causing a small shift in the observed small planet radii towards bigger planets.

The Gaia spacecraft’s billion-pixel camera maps stars and other objects in the Milky Way.Image credit: C. Carreau/ESA.

The same result was found in a parallel study led by Fulton, who found a 0.4% increase in planet radii from Gaia compared with the (higher precision than Kepler, but less precision than Gaia) results using Keck.

The papers authored by Berger and Fulton investigated the split in super Earth sizes on short orbits, confirming that the two planet populations was still evident with the high precision Gaia data. Further exploration also revealed interesting new trends.

Fulton noticed that two peaks in the super Earth population appear at slightly larger radii for planets orbiting more massive stars. This is true irrespective of the level radiation the planets are receiving from the star, ruling out the possibility that more massive stars are simply better at evaporating away atmospheres on bigger planets. Instead, this trend implies that bigger stars build bigger planets.

Models proposed by Sheng Jin (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Christoph Mordasini (the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy) in a paper last year proposed that the location of the split in the super Earth population could be linked to composition.

Planets made of lighter materials such as ices would need a larger size to retain their atmospheres, compared to planet cores of denser rock. If the planet size at the population split marks the transition from large rocky worlds without thick atmospheres to mini-Neptunes enveloped in gas, then it corresponds to the size needed to retain that gas.

Berger suggests that the gap between the planet populations seen in the new Gaia data is best explained by planets with an icy-rich composition. As these planets all have short orbits, this suggests these close-in worlds migrated inwards from a much colder region of the planetary system.

The high precision planet radii measurements from Gaia seem to leave our planet population intact, but suggest new trends worth exploring. This will be a great job for TESS, NASA’s recently launched planet hunter that is preparing to begin its first science run this summer. Gaia’s astrometry catalogue of stars will be ensuring we get the very best from this data.

Planet radii derived from new Gaia data and Kepler (DR25) Stellar Properties Catalogue. Red points: confirmed planets. Black points: planet candidates. Bottom: ratio between the two data sets. There is a small shift towards larger planets in new Gaia dataImage credit: Figure 6 in Berger et al, 2018.

References: